Inside figure skating’s reputation as the “world’s gayest sport”

BY ELLA MILLER

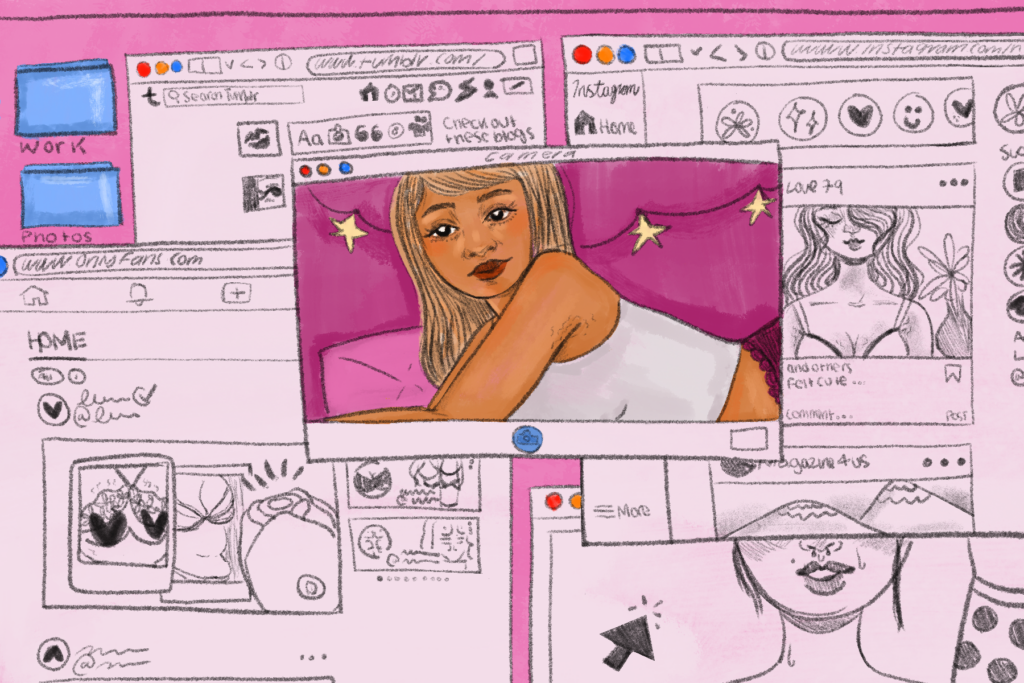

ART BY PRAPTI GOSAIN

———————————————————–

For Anthony Paradis, it all started at the Sochi 2014 Olympic Games. As the titular theme of Schindler’s List rang out across the ice, Yulia Lipnitskaya began her free skate program. She wore a bright red costume, an homage to a young character from the Steven Spielberg film. The Russian prodigy was only fifteen at the time, and with her rosy cheeks and wide eyes, looked not much older than the girl in the red coat to which she was paying homage.

Lipnitskaya’s performance brought the audience at Sochi to its feet, and Russian flags were hoisted proudly into the air. For seven-year-old Paradis, sitting in his living room in Boisbriand, Québec. It was enough to inspire a life and career in the sport.

“I saw her on our TV and I was like, Wow!” says Paradis, now seventeen. “All the things she could do on the ice, her flexibility, I was so blown away by her. From that point, I kept saying to my parents, ‘I want to do skating.’”

For many, this is how it starts. The desire to emulate these skating greats—their elegance, their artistry, their emotion—can drive children as young as two, three, or, in Paradis’s case, seven, to devote their lives to the sport. But as Paradis entered the realm of figure skating, he found himself navigating an industry fraught with biases surrounding gender, sexuality, and masculinity. Because of the sport’s association with traditionally feminine attributes such as delicacy, poise, and costume, men who dared cross that line—at least in North America—were entering a minefield of stereotypes and homophobic vitriol.

Eight months prior to the games in Sochi, Russia, President Vladimir Putin signed anti-LGBTQ2S+ legislation into law, prohibiting “propaganda” that promoted non-traditional sexual relationships, which could be interpreted to mean anything non-heterosexual. In spite of the legislation, seven openly gay athletes competed in the Games—all women, none in figure skating.

Figure skating has consistently been a popular sport within the LGBTQ2S+ community. Even in years when the sport was lacking in openly gay stars, there was still something very camp about it. There have been some gay participants, but few were willing or able to be open about their sexuality during the height of their careers. Homophobia meant coming out was strictly reserved for retirement.

The gay male figure skater had long been a trope in popular culture—think of the relentlessly repetitive punchline of the 2007 comedy film, Blades of Glory: Men? Figure skating? That’s so gay. The answer to why there were so few openly gay skaters active in the sport until recently is complicated. That’s because the politics of figure skating is a tangled web. It encompasses both international and interpersonal politics, as well as the ways in which assumptions of gender binaries interact—and interfere—with the perception of sports and athletes. It also taps into homophobia and LGBTQ2S+ discrimination, the taboo against men who express themselves in gender non-conforming ways, and the fear among figure skating’s governing bodies about the sport’s precarious reputation as nothing more than its kiss and cry.

How Men Started Skating

Figure skating was popularized as a sport for European elites in the late nineteenth century. It was considered highly formal compared to other athletic events of the time. Initially male-exclusive, it quickly developed a following and was comparable to modern track and field events, focusing primarily on the execution of jumps and tricks rather than artistic expression. After trailblazer Madge Syers placed second in an all-male division in the 1902 World Figure Skating Championships (which did not officially ban women), female divisions were eventually introduced to the sport. Later, music was integrated. To this day, men’s figure skating remains the only mainstream sport in which men utilize music in their performance, with the music most often sourced from the genres of musical theatre, ballet, opera, and the like.

Today, figure skaters are graded simultaneously on technical achievements and presentation. Technical elements include jumps and spins, which are scored based on their execution, with higher points awarded to more difficult physical tasks. The presentation score awards points for music choice, acting, and how well the skater conveys the story or themes of their routine. “I wish more sports had an emotional element,” says former figure skater Chris Schleicher, referring to figure skating’s unique combination of technical and presentation elements. “The women in gymnastics have music, and the men don’t. I feel like it’s probably because it looks too fruity for men to have some sort of emotion.”

The most damning explanation for figure skating’s association with male queerness is likely the overwhelming presence and popularity of women in the sport, despite its roots as a male-dominated sport. Figure skating first garnered popularity in North America’s mainstream thanks to three-time Olympian Sonia Henie’s Hollywood films, which depicted her as a graceful, über-feminine ice princess. This image was further propagated here in the Great White North by “Canada’s sweetheart,” Barbara Ann Scott, the 1948 Olympics champion. Figure skating thus became a sport associated primarily with women’s femininity—meaning that, whether or not it was true, many men who entered the sport were stereotyped as feminine or gay.

The dominance of female athletes meant that most male skaters—less popular than their female counterparts—tended to fly under the radar. For some, this may have been an opportunity to keep their personal lives separate from their careers, particularly in an era when openly acknowledging one’s sexuality carried significant personal and professional risks. While same-sex relations in Canada were decriminalized in 1969, homosexuality was still legally deemed a mental illness in Canada up until 1982 (2010 in Alberta). Legal protections under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms stipulating equal civil rights for LGBTQ2S+ people would not be ratified until 1996, well after the start of the AIDS epidemic. Legality aside, it was not safe to be gay for many Canadians. Athletes were no exception.

In the world of figure skating, the effects of the AIDS epidemic were inescapable. It claimed the lives of Olympic skaters and up-and-coming stars, choreographers, and world-level judges. AIDS was responsible for forcing many queer male skaters out of the closet. “It was largely Canadians who were in the first wave of people who were out, and a lot of it was because of AIDS,” recalls journalist and author Lorrie Kim, founder of the groundbreaking Rainbow Ice blog.

We now know that HIV/AIDS can and does affect people of every gender and sexuality, but in the 1980s and ’90s, it was known as the “gay cancer.” Those suffering were predominantly men who had sex with men. For figure skaters who died of AIDS, their deaths were also their coming-out moments. With the AIDS epidemic, figure skating suffered a significant blow to the core of its community. Individual skaters are the backbone of the sport and, ultimately, drive ticket sales and television viewership.

When Titans Collide

In order to draw high audience numbers, governing bodies like the International Skating Union (ISU) go to great lengths to publicize the biggest and most attractive personalities in the sport. In fact, creating rivalries is a fail-safe strategy to drive interest in any sport. Similar to professional wrestling, rivalry, and drama between figure skaters are exaggerated and played up to entertain audiences. “For that reason, queer people at the time were ambassadors for the sport,” says Schleicher on the personality-driven aspect of skating. As a result, male skaters who defied traditional gender norms were suddenly thrown into the media spotlight, for better or worse.

One of the most fondly remembered rivalries in figure skating history was between Brian Orser and Brian Boitano—or, as it was more commonly known, “The Battle of the Brians.” The American Boitano and the Canadian Orser had been tied neck-and-neck throughout the regular skating season. The match received top billing in high-circulation publications such as TIME and Sports Illustrated and stadiums were filled to capacity.

When the lights came up, Boitano would be the first to take to the ice. Clad in a blue suit, emblazoned with gold buttons and epaulettes, he took a cue from Napoleon, the military leader for whom his program was named. He flipped between powerhouse jumps and a slow, purposeful step sequence, truly absorbing his time on the ice. Next would be Orser’s turn to steal the show. He darted onto the ice dressed all in red—his maple leaf to Boitano’s stars and stripes. Orser, too, had gold epaulettes and a sash that caught the lights as he hurtled through the air, performing jump after jump. Both performances were exquisite, and the judges were split. In the end, the American, Boitano, would snatch the gold.

In 1997, Boitano would see his image reach a new demographic through the television show, South Park, in which a caricature of Boitano became a recurring figure. He appeared in the first season of South Park, ice dancing during a song about gay liberation, and continued to appear throughout the show and in subsequent films. Boitano did not come out as gay until 2023, as a response to his placement on the United States Sochi delegation, almost twenty years after his South Park character made its debut.

Meanwhile, Orser would have to contend with much more than a foul-mouthed cartoon. In 1998, an ex-partner filed a palimony case against him, and he was forcibly outed. Orser initially wanted to keep the suit private, fearing for his safety, but the courts denied his request. He now lives in Toronto with his husband, and is the coaching partner of Tracy Wilson at the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club. The club is unique in the sense that it is an ice rink exclusively for figure skating. The usual Canadian norm—figure skating comes second to hockey—does not apply to the Cricket Club. There is no problem accessing practice time, and it offers young skaters protection against violence, like homophobia, often found in mixed-usage arenas.

The Elephant in the Rink

All Canadians know that hockey is a way of life, with over half a million Canadians playing hockey (compared with just over 400,000 figure skaters nationally) and around fifteen million tuning into the NHL playoffs. The problem arises when the queer-coded world of figure skating comes into contact with the statistically homophobic realm of Canada’s national pastime: over 900 on-ice incidents involving homophobia and gender discrimination occurred in the 2021–22 hockey season, according to a Hockey Canada report. “You can’t go anywhere in the rink without there being somebody who’s going to be macho and prejudiced and make fun of a figure skater,” says Rainbow Ice blogger Lorrie Kim about this divide. “I have never been in a male locker room, but I feel fear if there’s a team of twenty hockey players in the locker room and then one boy who figure skates at the rink.”

In Canada, the gender binary that divides sports—particularly skating—starts young. Figure skating has long struggled with recruiting boys into the sport. A 2017 report by Skate Ontario, a division of Skate Canada, revealed that seventy per cent of skating personnel are female. Similarly, a 2023 report from US Figure Skating stated that only twenty-three per cent of figure skaters in the crucial twelve-and-under age range are boys. In Canada, this appears to be part of a cultural norm wherein little girls are given white figure skates, whereas boys are expected to wear black hockey skates.

“There’re so many small things that don’t make sense,” says Schleicher of the black and white binary of skates. “In single skating we do all the same elements, men and women. But men don’t do layback spins. I’ve always found this weird. And spiral sequences were a female thing. There’s nothing inherently gendered about bending your back.”

“When I first started to realize that I might be gay, I — for real — went through a period of time where I thought I was the only one in the whole world.”

– Eric Radford

The mindset behind it is as simple as it is harmful: Figure skating is for girls; hockey is for boys. The stigma surrounding boys in figure skating can make it difficult to recruit them into the sport, which is integral to the survival of not only men’s solo skating but also any partnered skating. However, to recruit male skaters, the sport’s governing bodies historically focused not on the athleticism of the sport but actively tried to counter figure skating’s reputation as a sport for women and gay men.

Case in point: Elvis Stojko, the face of Canadian figure skating throughout the 1990s. Known for skating in blue jeans and leather jackets, he was heavily embraced as a figure who could provide a more “macho” image to the frilly world of skating. Stojko’s presentation and appearance stood out among skaters because of his refusal to adhere to its theatrical side. Rather than focusing on more traditional balletic lines, Stojko’s approach incorporated an intensely athletic, martial-arts style, which inspired a new mindset around masculinity in the sport. He was famously quoted as trying to change the perception of figure skating as a “sissy sport.”

Stojko’s image would continue to be replicated in marketing campaigns as a means of defining masculinity within the sport, including Skate Canada’s controversial “Tough” campaign. The campaign faced heavy criticism for overemphasizing physicality at the expense of artistry. Although it was eventually cancelled, “Tough” served as an important milestone for understanding how even figure skating’s governing bodies reinforce heteronormativity and gender binaries within the sport.

When to Come Out

“When I first started to realize that I might be gay,” says Eric Radford, “I — for real — went through a period of time where I thought I was the only one in the whole world because I didn’t see it anywhere else. I didn’t know anybody else.”

Radford, who grew up in Red Lake, a small town in northwestern Ontario, had his first encounter with queer culture through figure skating and his coach, Paul Wirtz. “Paul, who I met when I was fourteen, when I moved to Montreal, was the first out gay person that I really met. And I was shocked.”

When Radford was named to Team Canada’s delegation for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, he considered coming out as a political stance. “I was given the opportunity to come out before that Olympic Games,” he says. “I remember getting off the phone with a call and thinking: Okay, I’m going to do it. It’s for something that’s bigger than just sport.” Radford told his parents what he was planning to do and, for the first time in his life, his unconditionally supportive parents doubted their son. They were concerned for his safety, being well aware of Russia’s new anti-LGBTQ2S+ policies. Radford’s parents’ hesitation made him question his decision: did he really want his first Olympics to be about his sexuality?

In the end, Radford decided not to come out. Despite his strong showing in Sochi—where he and partner Meagan Duhamel won silver in the team event—he says he felt as if he were taking the coward’s way out. Still, he says the people he met there made him feel safe. “Later that year,” he says, “in the middle of the best season Meagan and I ever had—we had an undefeated season and on the way to winning our first world title—I came out when I felt comfortable and when I felt ready. It was done better, and maybe had a better impact because I was in a better place to talk about it authentically.”

Radford was the first elite-level figure skater to come out at the height of his career. He made history again with a third place finish in pair skating and a gold in the team event at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. He became the first openly gay man to win a Winter Olympic medal.

At his final Olympics, the 2022 Beijing Games, there were more openly LGBTQ2S+ men and women competing than ever before in figure skating history, according to the Human Rights Campaign, with ten queer athletes competing, most of them men.

Following his retirement, Radford joined the ISU’s Athlete Commission, where he liaised between figure skaters and their governing body. Systemic changes have rapidly changed the face of figure skating for the better. One of Skate Canada’s major recent changes is to the definition of teams. Rather than comprising a man and a woman, skating teams are now officially made up of a “Skater A” and “Skater B,” in an effort to promote gender diversity and non-discrimination against trans and non-binary folks, such as former American pair skater Timothy LeDuc. These changes may eventually open the door for same-sex team skating, which already takes place at the Gay Games, but is not currently allowed in any other major sporting events.

Team skating storylines typically revolve around romance plotlines, which may contribute to the same-sex team skaters taboo. Allowing same-sex couples to skate together to romantic storylines could risk provoking backlash from more conservative audiences at home and abroad. However, it could also open the doors for a more inclusive, more creative culture in figure skating — especially for those who are sick of heteroromantic storylines. “I got a free pass from that storyline,” says Schleicher, laughing, “because my partner was my sister.” The pair mainly performed routines themed around the joys of skating.

Innovation and Storytelling

Anthony Paradis is now seventeen and busy reshaping men’s skating. His on-ice persona is bold and uncompromising, defying gender norms in glamorous makeup and androgynous costumes. He has already won medals at three different Canadian championships. “I don’t watch a lot of skating because I feel like it impacts my creativity,” he says. “I just like to get ideas from my mind.”

However, Paradis has always worshipped at the hallowed halls of Jason Brown, Yuzuru Hanyu, and Evgenia Medvedeva—all famous skaters known for innovations in the sport and storytelling ability, which Paradis places above all else when designing his routines.

Paradis’s rise and the positive reception of his queer-inspired, highly conceptual programs have not negated the continued existence of homophobia. In 2023, U.S. skating star Ilia Malinin made jokes about pretending to be gay in order to up his scores. “I remember feeling so bad because, well, are all my efforts just being rewarded because I’m gay, or is it because I’m good at what I’m doing?” asks Paradis. But he adds that Malinin has learned from the incident, and that after speaking with him, he’s made peace with it.

The version of figure skating Paradis is poised to inherit is not perfect, but major strides have been made since 2014. As is the case with the advancements of LGBTQ2S+ rights in any capacity, change is slow but continual. And maybe one day soon, the world’s gayest sport will be able to wear its crown proudly.