Toronto’s transit and public spaces are torn. When City Hall can’t mend the fabric, tactical urbanists step up and stitch it back together

BY EDWARD LANDER

ART BY CALLIE SILVERTON

———————————————————–

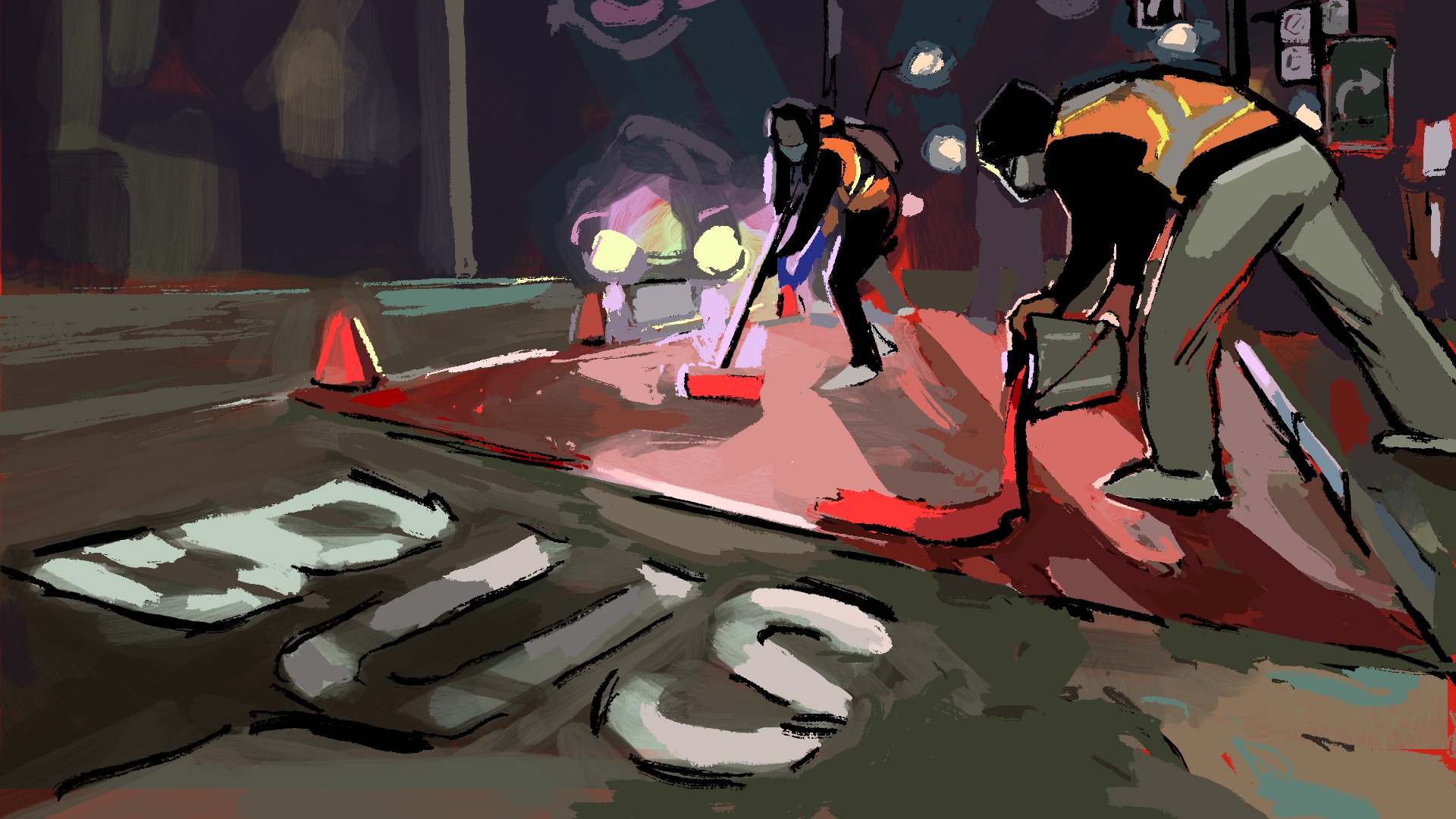

In the early hours of October 12, 2022, Vincent Puhakka and a dozen other TTCRiders members cycled, walked, and took the bus to the downtown Toronto section of Dufferin Street armed with mop buckets, rollers, and several jugs of bright-red Crayola children’s paint. The members of TTCRiders had transformed into bandits, thieves in the night, camouflaged in high-vis vests and steel-toed boots.

The crew had been preparing the plan for a week. Tensions were high, but on the morning of the stunt, nerves were replaced with a kind of cautious giddiness—they were going to pull it off. The crew stencilled out and painted fifty feet of illegal, makeshift bus lane in the right-most southbound lane of Dufferin Street.

This was far from business as usual for TTCRiders, a group that normally focuses its advocacy efforts on petitions, rallies, and other less aggressive outlets. The decision to take this action stemmed from what Puhakka describes as a “very specific set of circumstances.”

Dufferin Street is unpleasant for everyone—drivers, pedestrians, cyclists—but especially those aboard the loathsome 29 Dufferin bus. Last January, the bus route was named the slowest in the entire city, with a peak travel speed of 10.6 kilometres per hour—a maddening figure for the approximately 20,000 people who rely on it daily.

A ride on the twenty-nine can feel more like a voyage on a ship in a storm, accompanied by a window-rattling, seat-lurching bumpiness that’s a hallmark of Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) buses. While the uncomfortable turbulence of the twenty-nine won’t interrupt a commute, the incessant traffic on Dufferin Street just might. It’s not uncommon for the street’s four lanes to be packed bumper to bumper, trapping the twenty-nine in gridlock. A chorus of sighs accompanies every screeching full stop. A gallery of disgruntled faces is the first thing to greet anyone who steps aboard during rush hour. In the morning, these faces are filled with the fear of being late for work; in the evening, they reflect the fear they can’t escape from work fast enough.

The anger caused by the twenty-nine doesn’t get left at the bus stop. The route has been unaffectionately branded as the twenty-nine “Sufferin” by locals, a bitter moniker that can be found printed on t-shirts, pins, and coffee mugs at shops in the West End. A Facebook page dedicated to the route sits ready to receive riders’ pent-up rage in the form of bitter rants and posts. Locals treasure the fail-safe excuse that the twenty-nine provides for any unwanted tardiness: “Sorry, I took Dufferin to get here.”

In 2021, good news for riders of the route arrived with the launch of the TTC’s RapidTO Surface Transit Network Plan. The initiative proposed transit priority lanes on five of the city’s busiest routes, including Dufferin, extending from its southern terminus north to Wilson Avenue. This felt like a real win for the thousands who ride on Dufferin; a priority lane would allow the twenty-nine to cut swiftly through traffic on the busiest part of the street.

Four years later, the red-paint saviour of the twenty-nine’s riders is nowhere in sight. Maybe the city should be given the benefit of the doubt—RapidTO was meant to be a five-year plan—but how long does it really take to install a bus lane? It’s only paint and signage, after all. The Toronto transit advocacy group TTCRiders raised the same question in October 2022. But rather than protest, demand answers, or cross-examine a TTC official, the group decided to take matters into its own hands.

Transit riders craved bus lanes, but the city simply wasn’t installing them quickly enough. Commuters on Dufferin and other busy routes watched enviously as lanes were installed on Eglinton Avenue, Kingston Road, and Morningside Avenue while they waited patiently for their moment in the spotlight. “Sometimes you have to do something a bit different,” says Puhakka, describing the idea’s inception. “It can be a slog if you’re constantly just trying to canvas people at a bus stop or get them to call their councillor.”

Puhakka has extensive experience with the latter. Although he works in insurance, his passion is urban planning—he’s been interested in it for as long as he can remember. He writes opinion pieces promoting or denouncing transit policies and regularly appears in the news, voicing TTCRiders’ views on Toronto’s transit problems. “We thought, why not shame the city by showing just how easy it is to put in a bus lane,” he says. “So, we did it ourselves, in the morning, with children’s paint.”

This was hardly the first time an urbanist group had been transformed from advocates to instigators. In fact, there’s a name for the kind of action that TTCRiders undertook: tactical urbanism. Defined as “an approach to neighbourhood building using short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions to catalyze long-term change,” the method takes many forms: installing DIY benches at bus stops, dismantling anti-homeless architecture, painting crosswalks, and, of course, reconfiguring the network of painted lines that control our streets.

The term itself was popularized in 2010 by adherents to the school of thought known as New Urbanism, a movement that promotes environmentally friendly habits such as walkable neighbourhoods. One faction within the movement, who referred to themselves as “NextGen,” had gripes with the New Urbanism and believed it was in need of rejuvenation. At an annual congress of New Urbanists in 2011, they pleaded their case for a new way of thinking—one that put the responsibility on the individual to create change. If cities are to become more sustainable, walkable, and liveable, they argued, it’s up to each of us to do our part.

The group published its program in a twenty-five-page pamphlet, “Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change.” The text was released online, available free for download. It immediately became popular amongst urbanist circles. Shortly after, a second volume came out, chock-full of insight from new devotees of the now-growing movement. These texts are like a bible to some DIY urbanists; they don’t just explain the philosophy behind the movement, they provide readers with the how-tos for participating in these actions themselves.

The tactical urbanism NextGen outlined was often about creating permanent change—but TTCRiders’ bus lane was never meant to last. Crayola paint is washable, and the forecast called for rain that night. Puhakka believes tactical urbanism is more about drawing attention to problems rather than solving them for good, but TTCRiders’ unauthorized lane certainly drew attention. “It went gangbusters,” says Puhakka, describing the media fallout. “As a stunt, it resonated for days online. I’d say it absolutely moved the conversation forward.”

The action was reported on BlogTO, TVO, and other big names in Toronto’s media sphere. But after the lane washed away, it was difficult to argue that much of anything had changed. According to the City of Toronto, the installation of bus lanes on Dufferin Street is now scheduled for early next year, and roadway studies are underway right now. However, it wasn’t Puhakka’s crew that set this into motion—it was the pressure to have reliable bus service for when the FIFA World Cup comes to Toronto in 2026.

Tactical urbanism has its own history in Toronto, far beyond TTCRiders’ action. While its origins in the city are unclear, examples of actions are plentiful, and numerous groups and individuals have applied the method in an attempt to deal with the urban issues the city faces. However, these actions are not always well-documented, and it’s not always clear whether they’ve led to change.

The Organization

Tactical urbanist actions in Toronto have historically been documented by a man named Martin Reis, a German-born photographer and performance artist. Reis photographed TTCRiders’ action in 2022, but it’s not the only event he has attended. Last August, dressed in a soccer referee jersey, Reis handed out yellow and red cards to bad drivers at downtown intersections. He’s also one of the minds behind an unsanctioned art installation painted across three houses slated for demolition near Casa Loma. Most notably, Reis served as the official documentarian, media liaison, and occasional participant in the guerrilla actions of the Toronto Urban Repair Squad (URS).

The URS was entirely dedicated to tactical urbanism. As the self-described “antidote to the poison that is the car,” their portfolio of work was diverse: makeshift crosswalks, signage reconfigurations, impromptu street closures, and their forte: the DIY bike lane. In 2007, the URS painted more bike lanes than the city did. Four years later, it installed Toronto’s very first separated bike lane (though the “separation” was a thin strip of Lego bricks and miniature traffic cones). Wherever the URS saw the need, it wasted no time in creating a lane, often reinstalling them after the city removed them. Its motto declared: “They say city is broke. We fix. No charge.”

Creating a functioning bike lane without equipment, money, or professional experience was easily accomplished, according to Reis. All the URS required to make one of their lanes was paint, tape, rollers, cardboard stencils, and guts. Its lanes cost a mere $80 per kilometre to construct, a figure that stood in stark contrast to the city’s, which can cost anywhere from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Although the URS’s goals were serious, its methods were often playful. Two members had cleverly adorned some of Toronto’s plentiful potholes with comic book–style graphics, reading POW! or THUNK! “The moment we did something that was quirky and fun, we got picked up by the news cycle,” says Reis. “That’s what the news cycle feeds off.”

Some actions were more adventurous than others. For example, the squad once replaced the “No Bicycles” signs at seventy-four TTC subway stations with new ones declaring that bikes were permitted. Seven teams of two worked all night to complete the task, and the signs at Spadina Station stayed up for nearly two years.

Although Reis could speak endlessly about the stunts the URS undertook, he’s sworn not to reveal who else was involved in them. The reason is obvious—its actions were illegal. According to Reis, though, the individuals behind the URS’s daring exploits were always changing. Sometimes, the perpetrators were a tight-knit group of experienced activists; on other occasions, their endeavours were coordinated alongside passionate community members.

Today, the squad is largely gone. Most members have drifted away, and some have joined other advocacy organizations. One member now works for the city’s Planning and Development Department, allegedly designing bike lanes. But, during its years of operation, the URS’s actions were almost nonstop.

Reis’s favourite action was back in 2009, what he called the URS’s “Easter present” to Toronto. The group wanted to publicly declare that the city wasn’t meant exclusively for cars, and it wanted to do it somewhere everyone would see. Ultimately, it selected the colossal “Toronto” sign by the Gardiner Expressway as its canvas—in plain sight of the approximately 140,000 drivers who drive past it daily.

Activists might be so impatient that they can’t wait for bike lanes to be painted or transit to get built, but still, getting up in the middle of the night, cycling across the city, and painting an impermanent lane could land a person in jail.

On the night of the act, the URS members cycled towards the site, with one towing a trailer, its contents covered with a bright orange tarp. Beneath it were two twelve-foot-long, white-painted, plywood cut-outs—one in the shape of a crosswalk-style “walk” figure and the other a cyclist. The group climbed over guardrails and slinked through the topiary shrubs that adorn each side of the city’s logo. They laid down the two figures, one on either side. “It was an operation with, like, twenty people,” says Reis. “We had to use walkie-talkies.”

The method that got projects like these off the ground was outlined in a manual that all members became familiar with. In six steps, it explained how to engage in tactical urbanism and, perhaps more importantly, how to get away with it. Scrawled in the margins between the steps were useful tips, likely learned the hard way during actions gone awry. “Have a story ready and play the part,” one instructed. “Don’t Get Cocky!” declared another.

The group was caught only once. A URS contingent had just finished reconfiguring the intersection at Dundas Street and Sterling Road when police cruisers flew in. The activists immediately scattered, darting in all directions. No guerrillas were apprehended that morning, but police confiscated a few bicycles and some supplies.

The URS was guided by a founding principle, a sentiment expressed in a quote by the American architect Buckminster Fuller that lives permanently on the sidebar of their blog, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” The URS’s actions sought to do just that. How could the city justify removing bike lanes that cyclists had already started using, or a crosswalk that made a trip to the park safer? With each action, they put the city on the spot, and with fingers crossed, they’d make the right choice. Sometimes they did.

The Beach Bum*

Toronto’s Bloordale Village is around 3.2 kilometres inland from Lake Ontario, but in May 2020, it saw a beach open right in its core. This wasn’t an ordinary beach. There was sand, but certainly no water. It was a popular spot for sunbathing or a campfire, but you wouldn’t find it on any tourist brochure. This sandy, tropical haven near the Dufferin Mall all came from the mind of one woman, Shari Kasman.

Kasman is a lot of things: an artist, a writer, a photographer, and a good friend of Reis. While she might not have seen herself as a tactical urbanist, she quickly became one when she had the vision for an empty lot in the centre of her neighbourhood. The corner of Brock Avenue and Croatia Street was once home to Brockton High School, a former TDSB vocational school that was demolished in 2019. When the school stood, wayfarers could easily pass through the parking lot as a shortcut to Dufferin Mall; however, after the school was demolished and the property waited for construction of a new secondary school, the site was fenced off. On occasion, visitors would remove fence panels in an attempt to bring back the shortcut, though they were quickly replaced by TDSB.

The space had become a wasteland, dusty and unused. One afternoon, Kasman spotted someone “lounging” shirtless on the other side of the fence. Inspired, she went home and called a friend. The two soon got to work creating some very convincing signage, using board panels. That same day, Bloordale Beach opened.

The very next day, it closed. The school board caught on to what had happened and sealed the gap Kasman’s friend had created in the fence. Kasman’s friend, determined to fulfil their vision, marched to the site and pulled the fences back apart. In spite of two more closures, people eventually caught on that the beach was open for good. As more people discovered the space, Kasman worried that passersby might be reluctant to visit if they thought they were trespassing. To counter this, she adjusted the city’s DANGER, NO TRESPASSING signs – instead of harsh warnings, they now welcomed visitors with sayings including LINGER, SO RELAXING.

The City of Toronto spends $22,534 per hectare to manage its parks yearly. When it came to upkeep, Kasman—operating on a budget which was presumably much smaller—had to get creative. When illegal dumping became a problem, Kasman feared clean-up crews would lock the gates on the way out. So, she reached out to her city councillor, and the messes were removed. On another occasion, someone dumped large piles of sand on the site. One visitor asked Kasman if she had ordered them herself; she hadn’t. But while she could see why the dumping of sand should be removed, she could also see the humour in it. Sand, of course, belongs on a beach.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bloordale Beach became a huge part of Kasman’s life and the lives of the people in the community. “People didn’t have events to go to during the pandemic,” she says. “This was a really nice, socially distanced way to do it.”

The gates of Bloordale Beach shut for good in September 2021, a closure that had been prolonged by persistent gardeners who wanted a chance to harvest the vegetables they’d been growing on the site.

When Kasman says the beach left a legacy, she means it. In addition to a number of news appearances, it inspired poems, a documentary, at least four songs, numerous films, and a handful of performance pieces. There’s even a petition to name the new high school “Bloordale Beach Collegiate Institute.” The influence was far-reaching. In a video message to the Bloordale BIA, then-mayor John Tory cited Bloordale Beach as an attraction in the neighbourhood. “People said to me, ‘Is that a deepfake?’” says Kasman. “I didn’t know what a deepfake was.”

Kasman now considers what happened at Bloordale Beach tactical urbanism, and she’s proud of it. However, she’s surprised at how big it became and how many people it resonated with. “There are so many of these spaces that are sitting empty in the city and we’re doing nothing with them,” she says. “Why can’t they all be a beach?”

The Advocate

It may be worth asking what drives someone to tactical urbanism in the first place. Activists might be so impatient that they can’t wait for bike lanes to be painted or transit to get built, but still, getting up in the middle of the night, cycling across the city, and painting an impermanent lane could land a person in jail. Jess Spieker, who knows more than most about how dangerous Toronto’s streets are, has an answer. In 2015, Spieker was cycling to work on Bathurst Street when a reckless driver collided with her, resulting in a broken spine, soft tissue damage, and a traumatic brain injury. After her accident, she became involved with Friends and Families for Safe Streets (FFSS), a group that hosts support meetings for crash victims and their families.

Every year, on the third Sunday of November, FFSS holds a vigil to commemorate the World Day of Remembrance for Road Traffic Victims. For Spieker, who now runs the event, this is one of the most important days of the year. During the remembrance walk in 2023, Spieker took attendees down Bloor Street West, pointing out safety issues along the way. I tagged along.

The group began at Kipling station and ventured east down Bloor Street. Spieker led the crowd, holding a microphone and towing a speaker that teetered on a cart behind her. At each intersection, Spieker listed the number of pedestrian and cyclist collisions that had taken place there. At Bloor and Lothian: twenty-three. At Bloor and Monkton: twenty-four. Toward the start, these figures were followed by subtle gasps, but the further we travelled down the street, the group got quieter. Bloor and Aberfoyle: fifty-five. Bloor and Kipling: a whopping 341.

We approached the bridge carrying Line Two of the subway over Bloor Street. Spieker pointed out the speed limit sign of 60 kilometres per hour. Just beyond it, another sign directed cyclists to merge with traffic just before the bike lane abruptly ended, putting riders in an unsafe competition with high-speed traffic.

Spieker stopped in front of a pub at Bloor and Eagle Road, where a sedan had parked right at the crosswalk. Through her microphone, Spieker pointed out the safety hazard this posed to the group, loud enough for the driver to hear. He frowned and reversed away from the intersection, avoiding eye contact with the group as we crossed in front of him.

We trudged further down Bloor as the sun set, the tea lights and LED candles strapped to attendees’ bicycles becoming more visible against the backdrop of the night. We walked into the parking lot of Tom Riley Park, where Spieker stepped up onto one of the large stones that prevent cars from entering the park. She told the group that we were going to begin the name-reading ceremony, which serves as a way of honouring the pedestrians, cyclists, and other vulnerable road users who had been killed on Toronto’s streets—the ones FFSS was able to find, at least. When she began reading, I tried to tally them up in my head; she had only reached the ‘D’ names when I lost count and gave up.

Leaving the event, one couldn’t help but feel angry—angry at all the reckless, drunk, and distracted drivers. Angry at the city for being five years too late to install the bike lanes that could have saved the fifty-eight-year-old woman killed at Bloor and St. George Street or the eighteen-year-old boy at Bloor and Avenue Road. One couldn’t help but see exactly what motivates an activist to take things into their own hands, to pick up a paint roller or to deflate the tires of an SUV. To risk fines, being arrested, or getting fired from their job, to do anything and everything they could to fix this city’s shamefully dangerous streets before yet another life is lost.

The Changemakers

The tactical urbanism Reis dreams of isn’t about fighting the city. He’s not looking for clashes with police or a back-and-forth battle with council. He doesn’t want a tit-for-tat where citizens install infrastructure only to have it swept away by city employees. Reis sees a future in which everyday people work alongside their cities to improve them, one where people don’t just inhabit public space but actively create it. That’s what the URS strived for and what Bloordale Beach was all about.

On a warm summer evening in 2016, a dozen URS members strolled into Kensington Market. Reis followed close behind with his camera. One man carried a wooden ladder over his shoulder, and another held a stack of bright white foam core boards. With the help of a vinyl cutter, these boards had been fashioned to look like speed limit signs that read “Maximum 10 kilometres per hour.”

The team reached Kensington Avenue through a laneway and got to work. They covered each of the original forty-kilometres-per-hour signs in the dense, historic neighbourhood with their improvised ones. The new rules stayed in place for a little while. Motorists seemed to obey them without question; pedestrians and businesses appreciated the calm. As always, though, the city eventually discovered the unauthorized change. Shop owners and passersby watched as white city maintenance trucks pulled up to fix the alteration. But when the crews took down their ladders, Kensington residents were left surprised. The speed limit in their neighbourhood had been reduced to thirty kilometres per hour.

Was it the URS that prompted the change? Reis likes to think so.

*An earlier version of this article misstated Bloordale Beaches’ signage and creation. The article has been updated to reflect the correct information.