Despite almost a decade of screen slashings in Canadian theatres playing South Indian films, excited audiences still fill the seats to watch their favourite superstars

BY SAHAANA RANGANATHAN

ART BY SAHAANA RANGANATHAN

———————————————————–

Lights dim as a familiar “Hey! Hey! Hey!” drowns my ears. A sound etched into the crevices of my childhood. The bass vibrates through the itchy theatre seats as each letter in the word “Superstar” is spelled out in blue dots on the black screen. The cheers begin at the first “Hey!” and by the time “Rajini” flies onto the screen, clapping erupts. My friend cups her hands around her mouth to shout. I hesitate before following her lead, half expecting someone to stare us into silence. Most of my theatre experiences are so silent that getting up to use the washroom feels like an unnecessary disturbance. But here, my parents and their friends whistle from their seats. The prolific Tamil actor, Rajinikanth, hasn’t even appeared on screen, but the mere indication of his presence elicits frenzied cheers.

Amidst the cheers, the crinkling of a snack packet makes its way towards me. I turn to find my parents and their friends pulling small snacks out of a large plastic bag. The light from the screens bounces off their smiles as they enjoy the seats my brother and I fought for. For Petta, you can’t just stroll in a few minutes before the movie to leisurely select a seat. There’s only one theatre in Ottawa screening the movie and you can’t reserve seats ahead of time. Instead, we had to make the minimum 30-minute drive to a dingy theatre in Orleans, get there an hour early to purchase a ticket, and most of all, stand on either end of a row of seats after being forced to do so by my mother and saying, “Sorry, these seats are saved” to each of the glaring audience members passing by.

As I scream at the screen showing a man beating the shit out of ten to fifteen gangsters, all my built-up frustration melts. I feel my heart swelling up into my throat, as I become overwhelmed with the privilege of getting to watch one of my favourite actors on the big screen, hearing my mother tongue, and sharing this experience with so many. The truth is, I can’t remember the first time I watched a Tamil movie in theatres. Ottawa is the closest city to my hometown, Brockville, with a large enough South Asian diaspora, it seems, to support screening South Indian movies. Being far from the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) meant I didn’t have access to the theatres that only screened Indian movies. Year after year, my envy grew as I saw Hindi-language films, commonly referred to as Bollywood movies, screened consistently in Cineplex. It seemed so much easier and I didn’t understand why Tamil movies were never afforded the same kind of grand Cineplex stage. That is, until I heard about the screen slashings. I started hearing the rumours when I was in the second year of my undergrad. Larger theatre chains like Cineplex did try to screen Tamil movies. Then they abruptly stopped. Someone slashed their screens in the GTA and in response, Cineplex refused to screen any more Tamil movies. The worst part is that, allegedly, these screen slashings were orchestrated by people within the community.

Vandalism

The earliest reports of the vandalism date back to 2015 when two screens were slashed at a Cineplex in the GTA playing the Tamil movie, Thangamagan. A year later, in 2016, the Scarborough Town Centre theatre and three Cineplex theatres in Brampton, Scarborough, and Mississauga were evacuated after a pepper spray-like substance was released on guests. All the theatres were screening the Tamil film, Theri, and Cineplex cancelled future screenings of the movie in the GTA. Following this, social media accounts alleged that the vandalism was part of a coordinated attack perpetrated by three theatres to maintain a monopoly on the market. The independent theatres—Scarborough’s Woodside Square Cinemas, Etobicoke’s Albion Cinemas, and Richmond Hill’s York Cinemas—released a statement calling the allegations “categorically false.” York and Woodside Cinemas also cancelled all screenings of Theri in response to washrooms being vandalized at the York Cinemas location. In 2019, a noxious substance was released at Landmark Cinemas in Kitchener-Waterloo before the screening of the Telugu film, Sye Raa Narasimha Reddy.

“They screened Vendhu Thanindhathu Kaadu, and that’s when the attack in the Calgary Landmark Cinemas theatre took place.”

When theatres reopened in 2021, Cineplex locations in Oakville and Richmond Hill screening the Malayalam film Kurup were vandalized, with a total of seven slashed screens. In February 2022, vandals began targeting small and independent theatre chains. Princess Theatres in Uptown Waterloo, Cine Starz’s Brant Street location,Oakville’s Film.ca, and Cinema Theatres Waterloo, had a total of six screens slashed prior to screening Bheemla Nayak. Community members developed GoFundMe campaigns for both Film.ca and Princess Theatres in order to help them cover the costs. By July 2022, Dean Priestley and Mohammed Yousafzai were arrested and charged in relation to the incidents of vandalism at Cineplex theatres in Oakville and Richmond Hill in 2021. Yousafzai was also charged in relation to the slashing incidents earlier that year.

In September 2022, two men slashed a screen and released a noxious substance during the screening of Malayalam film, Palthhu Janwar, at Landmark Cinemas in Kitchener. A few days later, Landmark Cinemas in Calgary, while screening the Tamil film Vendhu Thanindhathu Kaadu, was vandalized when pepper spray was released upon the concession area. Later that month, KW Talkies, distributing the Tamil film Ponniyan Selvan 1, tweeted that theatre owners in Hamilton, Kitchener, and London had received threats in an attempt to prevent theatres from screening any movies from that distributor. KW Talkies tweeted a screenshot of an email saying, “Warning to theatre owners and workers if you are planning to play movies from organized criminal KW Talkies Saleem, specifically movie PS1 and Chup. We will tear up all your screens and release toxic in the area and your employees will end up in the hospital.”

Saleem Padinharkkara is the CEO of KW Talkies, which was founded in 2019. They distribute different genres of Indian movies including, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Hindi. Padinharkkara argues that the high prices for movie tickets are related to the monopoly a few theatres and distributors have on the market. According to Padinharkkara, Landmark was still willing to screen Tamil movies in Western Canada in 2022. They screened Vendhu Thanindhathu Kaadu, and that’s when the attack in the Calgary Landmark Cinemas theatre took place. Padinharkkara explains that Cineplex agreed to play the Hindi and Malayalam versions of Ponniyan Selvan 1, but did not screen the movie in its original language, Tamil. Landmark was hopeful to play the movie in Tamil until they were attacked and received threats. “I had sent a request to all these independent theatres, to Highland and to Princess Theatre in Waterloo, Film.ca, and all these different locations,” says Padinharkkara. “And then everyone received this email.”

In response, Padinharkkara says some theatres backed out of screening Ponniyan Selvan 1 but theatres like Film.ca continued to support them. During this wave of attacks, Film.ca CEO Jeff Knoll shared a statement on social media promising to ensure the safety of their staff and patrons. Importantly, Knoll emphasized Film.ca’s commitment to screening Ponniyan Selvan 1, saying, “We stand with our Tamil friends and neighbours as well as all others who want to enjoy the magic of the movies in English, Tamil, or any other language.”

Padinharkkara also recalls another incident in 2020 when KW Talkies purchased the distribution rights for the Tamil movie, Karnan. At the time, KW Talkies was working with Cineplex. Padinharkkara tried to get the Atlantic Canada Cineplex locations to screen the movie by arguing that most of the attacks were concentrated in the GTA. Cineplex initially agreed and KW Talkies began its first promotion, that was until KW Talkies received an anonymous call. According to Padinharkkara, the caller said they were making a big mistake. “You shouldn’t be getting Tamil movies, you just stay in your lane and just get Malayalam movies,” they said allegedly. The next day, Cineplex emailed him saying they were not comfortable playing these movies, as they had received threatening calls. Padinharkkara also highlights that outside of Cineplex and Landmark, there are not many other major chains that have locations across Canada. For Padinharkkara, two major theatre chains refusing to play Tamil movies make it significantly harder to recover capital.

Joe Castaldo, a journalist for the Globe and Mail who reported on the vandalism, explains that determining the number of incidents was difficult because the press and the police treated these acts of vandalism as isolated incidents at first. He had to collect information mostly based on old articles, speaking with film distributors, theatre owners, and the police. Since Castaldo and the Globe broke the story, these vandalism incidents have started to be treated in connection to each other by the media and police. In March of this year, moviegoers were pepper sprayed in a Landmark Cinemas in Surrey, B.C. during the screening of a Sinhalese-language movie.Also in March, police started investigating if the incident is related to similar incidents in the Landmark Cinemas locations in Kanata, Ontario and Edmonton.Padinharkkara is confident that more media exposure to these vandalisms will create changes in the industry. The mystery behind who perpetrated these acts of vandalism remains unsolved. Allegations aside, the end result is the same, with independent theatres, new distributors, and audiences shouldering the loss.

First Day, First Show

On a cool December day, months after the Ottawa Movie Club watched Mani Ratnam’s blockbuster Ponniyan Selvan 1 in theatres, people pile into a suburban house in Kanata to discuss the film. The menu for the meeting includes the usual South Indian specialties: soft idilis, spicy sambar, saffron-scented payasam, crunchy vadai, coconut chutney, and a seven-layer chip-and-dip appetizer as a palate cleanser. A big meal paired with warm conversation.

Meena Peruvemba, a member of the Ottawa Movie Club, scrolls through the 35-page summary of the historical fiction book that Ponniyan Selvan 1 is based on. For Peruvemba, she watches movies just for entertainment’s sake, also known colloquially as a “time pass.” I met Peruvemba through my parents around 2016, and since all of us are “movie crazy” she always asks me if I’ve seen the latest Tamil movie. I usually find myself responding with, “It’s on the list!” She’s one of the few people I know who makes it a point to try to attend the first show on the day the movie releases. “I know the pain of not having a theatre to watch Tamil movies,” says Peruvemba. She moved to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, in 1985 from Bangalore, India. At that time, watching a Tamil movie in theatres was impossible. There wasn’t an audience for it.

“All the kids would play in the living room as the parents would watch five to six movies, starting on Saturday morning at 11 a.m. and finishing by Sunday evening.”

When she first came to Canada, Peruvemba had bigger priorities: studying, working, and raising children. “We adapt to the new culture and integrate to the new culture, but somewhere in the back of our mind, we missed that culture,” she says. Within her first few years in Canada, her knowledge of the Tamil alphabet got rusty, not having seen it written anywhere.

Peruvemba associates going to the movies with big holidays like Diwali, the festival of lights. The culture of movie-going centres around holidays spent with family, eating and going to the newly released film. Movies became “one way of hanging on to our background, our ethnic culture, our heritage,” says Peruvemba. In Saskatoon, Peruvemba couldn’t go to the theatre, so she brought a piece of it home. Whenever one of her friends would drive to Calgary or Edmonton, they would get all the recently released Tamil movies or have the movies mailed to them. Then, a group would gather in the house of their only friend with a VHS player. All the kids would play in the living room as the parents would watch five to six movies, starting on Saturday morning at 11 a.m. and finishing by Sunday evening. Parents would take turns watching the kids and they would take breaks to eat together. Peruvemba says that for those few hours, “You kind of feel like you’ve gone back to India and come back.” Today, with easy access to streaming, she’s able to brush up on the Tamil alphabet at the click of a button. “Those things are still there—it’s not gone anywhere.” When Peruvemba diligently watches movies in theatres, it’s purposeful. Her logic is simple: if someone brings the movie to Ottawa, they need to be able to cover the costs of renting the theatres. “If they put in the effort to bring a movie, good or bad, I’ll go.”

Peruvemba didn’t hear about the vandalism but believes she saw it first-hand. In 2021, she went to watch Thalaivii, excitedly purchasing the tickets online and making her way to the South Keys Cineplex in Ottawa with her husband. After arriving she noticed a crowd at the front and police officers interrogating detainees. They were told the movie would not be playing that day and left. The next day she heard from members of her community that it was related to the vandalism incidents. Peruvemba stresses the importance of supporting independent cinemas, but when threats were sent to theatres screening Ponniyan Selvan 1, she considered not going. “Even when they released it, I was not sure whether I should go or not,” Peruvemba says, “It’s watching a movie, I want to be safe.”

Mass Masala Movies

Peruvemba’s focus on the entertainment factor of Tamil movies is not unique to herbut a convention of the genre. When I tell people about my favourite Indian movies, I always add the caveat that it’s not necessarily Bollywood. That’s not to say I don’t like Bollywood movies, but usually, people are picturing a different type of movie than the one I’m describing. I’m talking about a specific genre of movies referred to as mass—with a stress on the ‘aah’ sound—masala. Sreedhar Pillai, an entertainment journalist based in Chennai, explains that mass means a movie has all the commercial elements to attract audiences. According to Pillai, this includes the actors, action scenes, loud sentimental scenes, romantic plot lines, songs, and a “little bit of glamour.” Pillai says, “The idea is that a film gives you more entertainment rather than storytelling.” Audiences, specifically the “toiling masses,” find pleasure in watching major heroes dance, deliver badass dialogue, and fight in action scenes. “Till 2000, there was no other form of entertainment other than cinema.”

Pillai has been covering the Tamil film industry since 1995 and his liberal use of words like “bombastic” makes listening to him as entertaining as the films he’s reviewing. “First and foremost, India is made up of various industries,” he says. India is not a monolinguistic country; according to the last Census of India in 2011, the country has 123 major languages. Bollywood represents Hindi-language films. Other major languages like Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Marathi, Bengali, Punjabi, and Gujarati each have their own regional film industries. Pillai explains that Bollywood is well-known internationally because it was the pioneer in exporting films. According to him, Tamil films followed and entered the international market in a big way—specifically in the 1980s when stars such as Rajinikanth and Kamal Hassan acted in blockbusters such as Nayakan (1987), Moondram Pirai (1982), Thillu Millu (1981), and Moondru Mugam (1982). “Each cinema in each area is different,” says Pillai. That is, each film industry has its own genre conventions. This is important because “Cinema is part and parcel of Indian culture,” Pillai says. He explains that in the beginning, the blockbuster Bollywood films were usually romantic films or family dramas, but with “Tamil and Telugu movies, it’s more mass.”

“Try as you might, it’s difficult to truly recreate the environment at home. You can capture pieces of it, but to get the full experience, you must go to the theatre.”

Cinema Paithiyam (Movie Crazy)

Ottawa Movie Club member, Bharath Murali, is a fanboy. It’s the last day of Pongal, an annual four-day festival to give thanks for the year’s harvest, and he’s patiently waiting for the workday to end. Thunivu, starring Ajith Kumar, has finally made it to two CineStarz theatre locations in Ottawa. Murali avoided reviews, spoilers, and fan pages. He cues the soundtrack in his Toyota Corolla to hype him up as he and his wife make their trek to the CineStarz in Orleans. Murali missed the first showing of the action-heist movie in St. Laurent—he can’t miss the second one. “I usually go for the first day, first show,” says Murali, “As a fanboy moment, we really enjoy seeing the movies before others get to see it.” He’s been a fan of Ajith Kumar—real fans call him Thala—since Grade 6 when he watched Dheena. It’s been 20 years since the release of that film, and Murali has yet to miss watching an Ajith Kumar movie since moving to Canada in 2013. “I try to watch all the [Tamil] movies that get released here,” he says. Like Pervemba, he associates movies with the holiday season. “It adds a lot of nostalgic moments in our lives. And basically, this is one way of feeling grounded to our roots.”

According to Murali, Ajith Kumar has fans on social media but does not have an established fan club, even though that’s common for major actors in the Tamil film industry. Fan clubs do a lot more than just attend movies. They also do social welfare work such as food drives, blood donations, and volunteering with seniors, according to a fan club president who wishes to remain anonymous. “Every big actor does have a fan club and it’s up to every actor as to how they will channel

this,” says a fan club member. For instance, the Indian actor Vijay “is a common connecting factor for all of us, and we come together and do a lot of welfare activities on his behalf.”

The president explains that, in India, fans celebrate mass masala movies with these actors in a big way. There are huge cutouts and banners decorating the front of the theatres, fans bring sweets to give to others, and people play trumpets and bang drums. “All the festivities that you typically see in a big festival or in a wedding, they do all of that just to welcome the arrival of this movie,” says the president. Sometimes fans do a pal abhishekam, which refers to a religious ritual generally done in temples where milk is poured on a god or deity by devotees as an offering. Instead of a deity, some fans do this for their favourite actors. This fan club tries to bring some of that fan culture to the community in Canada. The first thing is they book the first show of certain Tamil movies, so fans can watch the first show on opening day. The leadership team uses their own money to buy the tickets for the movies, reserving them for their members. They also design special tickets, banners, and posters in preparation for the movie release. “We are not doing this for a profit,” the president says. “Every single penny that is being spent for things like banners—it’s our own money.” It doesn’t stop there for the president; he wants to entertain and hype the audiences, so they generally have dancing in the theatre before the movie.

Murali and the president illustrate that for mass masala movies, it’s difficult to replace the theatre-going experience. They fall into the category of what Pillai describes as the younger audience. Pillai says that streaming has drastically changed the cinema experience in India. The major demographic, between the ages of fifteen and thirty—is less interested in seeing art-house or dramatic films in theatres. It wants mass films with favourite actors. Pillai explains that with the advent of streaming, audiences want to go to the theatre for the experience, not just to watch a movie. Try as you might, it’s difficult to truly recreate the environment at home. You can capture pieces of it, but to get the full experience, you must go to the theatre. As a result, many of the films that have large theatrical receptions are usually big-budget movies, starring an actor with a strong fan base—like Ajith, Vijay, or Rajinikanth—with lots of mass elements. Pillai says that despite the changes brought by streaming, India still has a strong movie-going tradition.

Watching movies has also become a way for the diaspora to connect to the political climate in India. Tamil cinema has always been deeply intertwined with the politics of the state. For example, the former actress Jayalalithaa Jayaram was the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu and served for six terms between 1991 and 2016. Her mentor, another huge actor, Marudhur Gopalan Ramachandran, also known as M.G.R., was Chief Minister of the state for 11 years. Similarly, the president says that one of the reasons Vijay is one of his favourite actors is because, “You get the dance, you get a fight, you get a cry, you get a laugh, then, you also have a social message with that.”

Murali remembers as a student Cineplex and Landmark released Tamil movies in Ottawa and Toronto. “I really miss viewing some of the Tamil movies on a bigger screen with better seating and sound system at Cineplex.” He explains he doesn’t understand the rationale behind the vandalism.

The president echoes similar thoughts. As the father of a nine-year-old, he explains that people often go to movies with their families. He’s left asking, “Are you trying to make this an unsafe place for families to come and watch movies?” He explains that for the next generation like his daughter, movies are how they learn about their culture. “She’s seven years old, what culture am I going to show her, here sitting in Toronto.” The president says, “She learns Tamil by watching movies, she learns about the people, and what the customs are, through movies.”

Distribution

Movies are relatively cheap in India—which is why theatres have become a place for the community. Today, they’ve increased in price with many theatres operating on a tier system ranging from 30 INR (50 cents CAD) to 200 INR ($3.30 CAD). The more money you pay, the better seats you get and most people have a huge selection of theatres they can go to. In Ottawa, Murali has two locations to choose from to watch Tamil movies. According to Murali, prices can range from $18 to $30. With the average movie ticket costing $13.50, this means sometimes audiences for Tamil movies are paying close to, or more than, double the price.

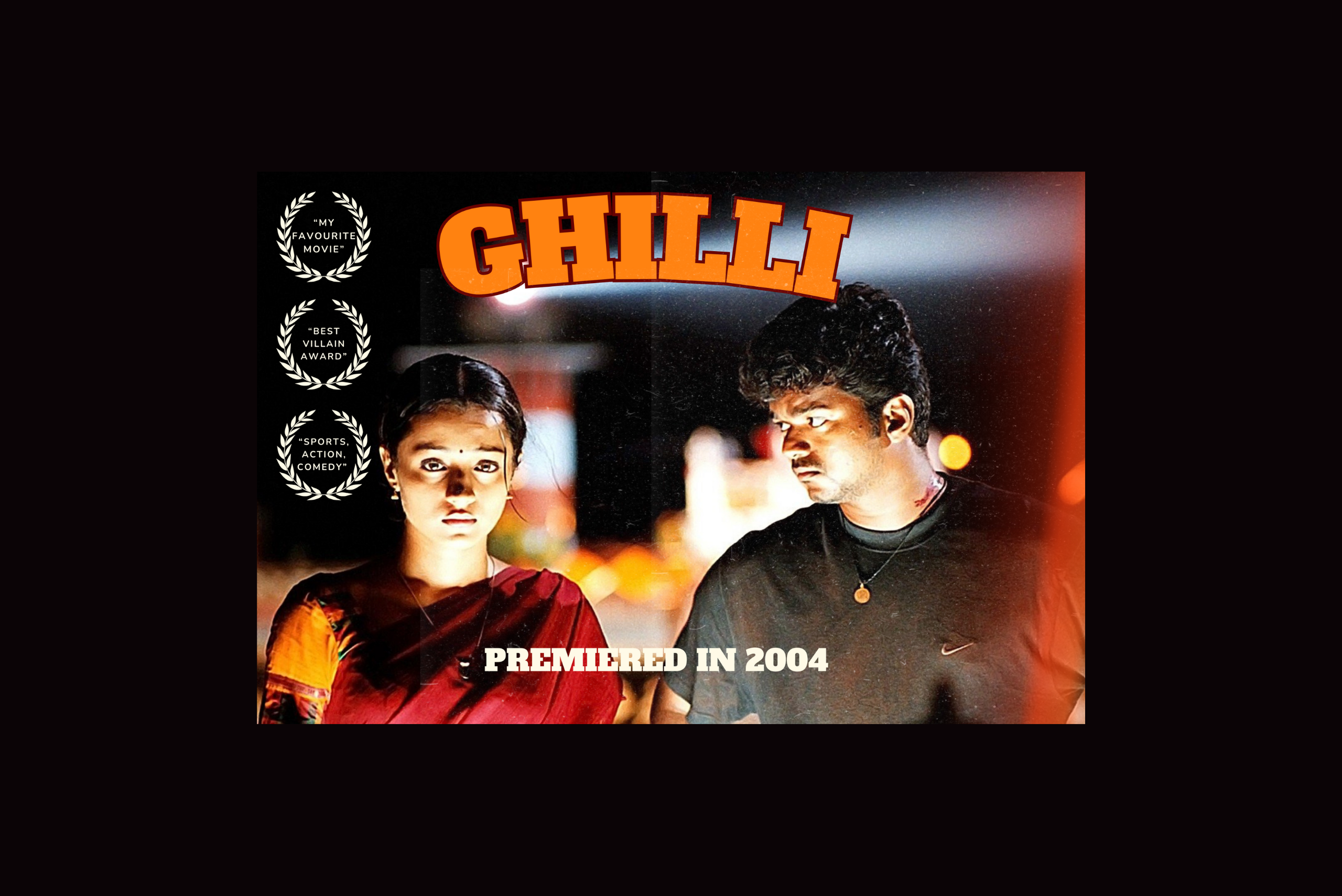

“The next two hours and forty-seven minutes are filled with one of the best sports-action movies I’ve ever seen. Scratch that. The best movie I’ve ever seen and I couldn’t talk about it with anyone outside of the four walls of my living room.”

Sen Rasaratnam, who screens movies in Ottawa, explains that there is another side to the story. He says that people have a perception that the lack of wide distribution means a lack of access. That is not necessarily the case says Rasaratnam, who started screening South Indian movies in Ottawa. Rasaratnam has called Canada home since 1990 and has become more involved in screening films since the release of the Telugu film Bahubali in 2017.Rasaratnam explains that larger chains like Landmark Cinemas and Cineplex require distributors to rent theatres for a week. They cannot rent for just a day or two. He says that the issue is, that in smaller cities like Ottawa, not every movie will attract consistent audiences for a week. Rasaratnam says that big-budget movies like Ponniyan Selvan 1 do well, but movies with fewer mass elements will draw less people, meaning distributors will have to cover costs. Rasaratnam says that independent theatres like Cine Starz will let them screen movies for two or three days. “We want to screen these movies,” says Rasaratnamm. “But not every movie is a big-budget movie,” Rasaratnam says they are negotiating to bring Tamil movies back to Cineplex and Landmark. However, even if they did get those larger chains, distributors would not get to choose the locations. He says, “Cineplex is not giving high-quality locations to South Indian movies.”

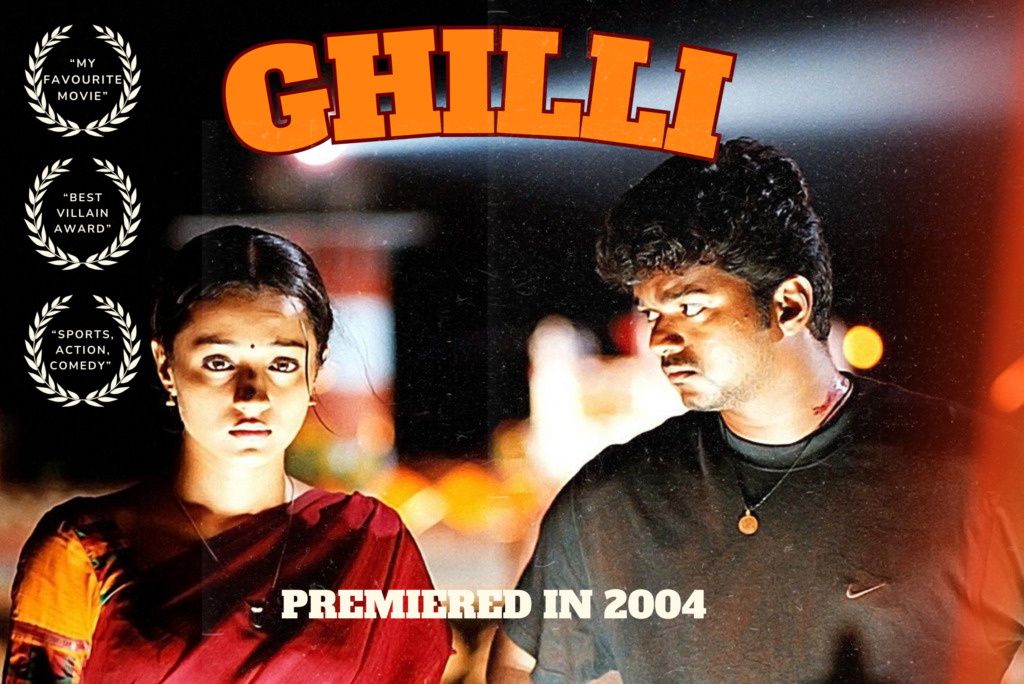

My Favourite Movie

I blow my hot breath onto the back of the scratched DVD and wipe it delicately before carefully placing it in the player. I pray that this time the combination of window cleaner and my saliva will make the worn-out DVD work. I return to my seat and cross my legs. My mom rolls her eyes but smiles anyway. She says, “I can’t watch this movie for the twentieth time.” My dad walks into the living room, and says, “Ghilli, again?” My brother and I glare at him. My dad joins us on the couch. The movie starts with white sneakers hitting the pavement. A shaky camera follows the main character, Velu, on his morning jog through the streets of Chennai. The next two hours and forty-seven minutes are filled with one of the best sports-action movies I’ve ever seen. Scratch that. The best movie I’ve ever seen and I couldn’t talk about it with anyone outside of the four walls of my living room.

Moving to a small town when I was six meant that no one in my immediate social circle spoke or understood Tamil. My grandparents, my aunts, uncles, and cousins were either in India or scattered across the world. I grew up having very few avenues to access and celebrate my culture. That’s what separates me and my brother from our parents. It’s not just a generational divide but also the environment in which we grew up in. Dramatically screaming “You wouldn’t understand” became our family’s motto. There are some experiences that my parents have had that I will never understand and vice versa but while watching Ghilli, I catch a glimpse of my smile in our living room mirror. I see the same smile my dad has when he talks about his favourite movie, Gauravam. It’s a legal drama starring his favourite actor, Sivaji Ganesan. It’s a movie he can recall half the dialogue from at the drop of a hat. Suddenly, the space between our lives shrinks.

I don’t live close to my family anymore. I moved to Toronto last year to pursue journalism. When we first moved to Brockville, it wasn’t a seamless transition. Some days, it felt like all I had was my family and movies. Despite moving to one of the most multicultural cities in Canada, sometimes I feel that same untethered emotion. The weight of a community no longer grounding me as I learn to lay a new foundation. It’s exciting and lonely at the same time. On the days I feel particularly separated from my friends and family, I find myself thinking that maybe it’s time to go to a movie.