BY MACENZIE REBELO

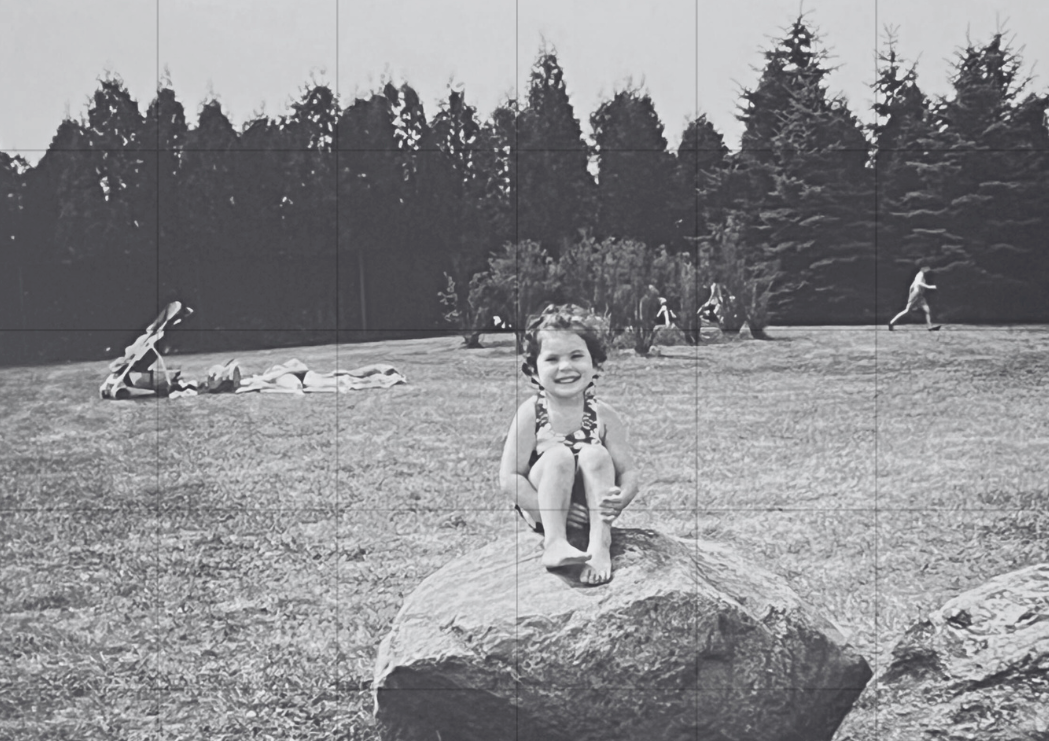

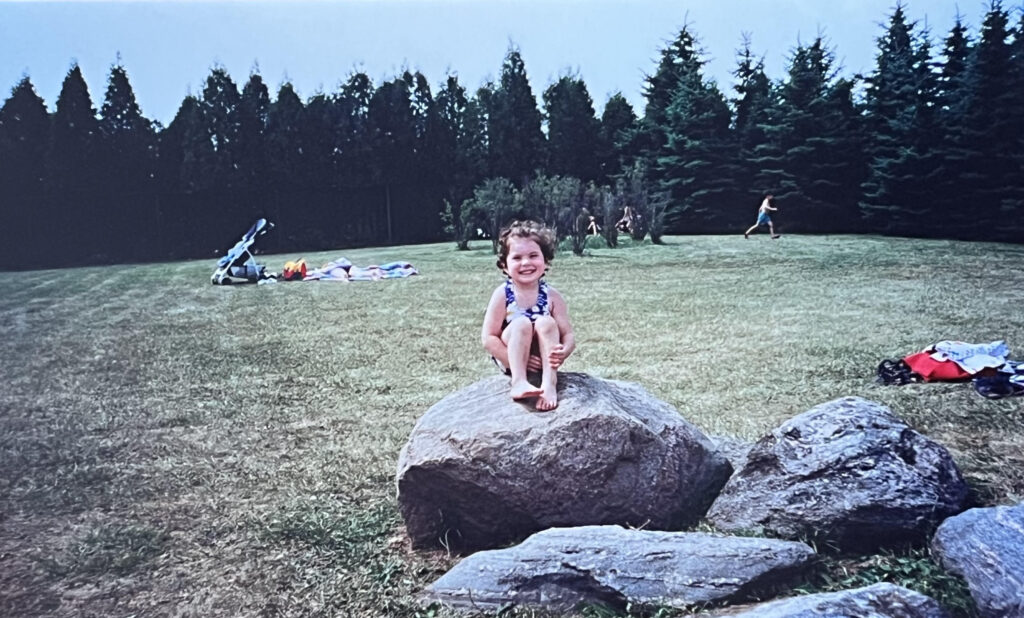

PHOTOGRAPHS PROVIDED BY MACENZIE REBELO

———————————————————–

I. Esperença

Esperança Da Silva sits in the brown leather recliner in a small, crowded two-bedroom condo in Brampton. She massages the Portuguese equivalent of Voltaren into the back of her knee. The piercing smell of medical ointment pervades the room, but it’s comforting and familiar to both of us. At four-foot-ten, the recliner seems to swallow her whole.

She pauses for a moment and shuts her eyes, basking in the short period of time where she has little to no pain. Seconds later, her eyes sluggishly open and she reaches for the tangerine she’d placed on the end table. Esperença attempts to peel the fruit but her hands don’t work like they used to. “It hurts my fingers,” says Esperança. “Let me,” I say, taking the tangerine from her. Esperança nods in approval. I peel the fruit and hand it back to her, slice by slice. She balances each wedge on her palm—her fingers don’t bend enough to grip them. “Do you remember how old you were when you were diagnosed with arthritis?”

“Growing up, the only thing I really knew about my grandmother was that she was suffering. Every time she sat down she would say, ‘Ai, Jesus.'”

She can’t quite remember, which isn’t wholly surprising for a 73 year old. “It has been a long time,” says Esperança, “I think I was 24 or 25.” Esperança hasn’t been able to articulate her thoughts well, at least since 2015 when she was diagnosed with dementia. I always find a way to understand her, though. She’s my grandmother; I’ve known her my entire life. Esperença is my mother’s mother. I call her Vovó (grandmother in Portuguese).

My Vovó was born Esperança Gouevia on December 19, 1950. She is the third oldest in a family of ten. In 1968, she left São Miguel and moved to Canada with her father. Vovó worked in a manufacturing factory in Brampton for a long time and in 1972 she married my Vovô, Jose Da Silva. My mother, Rosemarie, was born nine months later. Around this time, when Vovó was in her mid-20s, her hands and fingers began to throb with a dull ache. At first, she thought this was a symptom of factory work. But when the pain worsened, she sought a doctor’s opinion, who initially brushed off her joint stiffness as the flu. “The doctor said I had a cold,” says Vovó. Back in the mid-1970s, not a lot was understood about

autoimmune diseases because they were considered biologically implausible. Vovó says she was diagnosed with both arthritis and spondylitis ankylosans: a rare type of arthritis that creates inflammation in the joints and ligaments of the spine causing the back to be stiff and unmoveable. To my family, this is also implausible. It was uncommon for someone in their mid-20s to be diagnosed with both arthritis and spondylitis ankylosans, especially during this time period. When I tried to fact-check Vovó’s version of events with my mom, she insisted that Vovó was diagnosed with spondylitis ankylosans in her early 50s. José, my Vovô, can’t be the tie breaker because he typically wasn’t present for Vovó’s appointments. So it’s unclear when exactly she was diagnosed or started taking medication for her autoimmune diseases.

The majority of Vovó’s health records were lost when she moved from Portugal to Canada, so we’re unsure what her health was like prior to the 1970s. Vovó has a rather large chunk of muscle and skin missing from the left side of her buttock and hip area. It looks like something had taken a bite out of her. Vovó doesn’t know what caused this abnormality—she’s had it for as long as she can remember, which isn’t that far back. None of her siblings know what happened, and my great-grandparents are no longer around to explain. We just assume it was the result of some sort of freak accident. The only thing we know for certain is that Vovó started drinking heavily in her 50s to cope with the pain of her illnesses. “I was sad,” says Vovó, “So much pain.”

Growing up, the only thing I really knew about my grandmother was that she was suffering. Every time she sat down she would say, “Ai, Jesus.” I have vivid memories of her venting to me on the living room sofa, sitting in a position like the one she’s in now. At that age, I lacked the capacity to understand what she was experiencing. All I knew was that I felt sorry for her and never wanted to be in her position. Vovó stopped working around the age of 55 because of her pain and became a full-time housewife. She spent most of her time cleaning, cooking, or lying down with a heating pad watching telenovelas.

This is how I remember her best. I used to remember coming over and opening the front door to the smell of Fabuloso and her sitting on the couch recoiling in pain. As our conversation slowly comes to an end, I notice she’s becoming more and more agitated by my questions. Vovó shakily picks up a water bottle and sips it. The tremors in her hands cause her to spill water on her shirt. She hastily wipes it off and stares out the window. “I miss her so much, but I don’t see her anymore,” says Vovó. I don’t even have to ask. I know she’s talking about Lizette.

II. Lizette

Lizette Cabral is Vovó’s niece and my second cousin. She was born to Vovó’s sister Cidilia on September 10, 1982. Vovó was enamoured with Lizette and often looked after her. Despite their closeness, Lizette doesn’t see Vovó as often as she used to. In December 2020, Lizette almost passed away from COVID-19. She was walking up the basement stairs one evening when she suddenly fell backwards down the wooden steps onto the cold basement floor. Dazed and gasping for air, Lizette lay still, waiting for her parents to find her. The popcorn ceiling remained dark until the basement light flicked on moments later. Her parents frantically called 911. Paramedics carried Lizette upstairs to an ambulance that was waiting outside. “I felt fine,” says Lizette, “I thought I was breathing okay.” Oxygen levels that drop anywhere below 88 per cent are considered dangerous or even deadly. “But the paramedic looked really worried,” Lizette says, “And then I saw the oxygen machine. I was only breathing with 34 per cent lung capacity.” Like Vovó, Lizette is immunocompromised and has several autoimmune diseases. Around the age of three, Lizette’s mom, Cidalia, could tell there was something wrong. “It was her mother’s instinct,” says Lizette. “She took me to Sick Kids Hospital without an appointment and begged for a doctor to see me.” After several tests, Lizette was diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Better known as JRA, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune and inflammatory disease which causes your immune system to attack healthy cells in your body. The common traits of JRA are fatigue and tender, swollen joints. Lizette had all the symptoms. Her diagnosis was not a shock to Cidilia or our family—almost all the women in the Gouevia family have some sort of autoimmune disorder. It can be as minor as eczema or as severe as lupus. The women in our family have unintentionally passed down a genetic curse to their children. When my mom was born without any illness, it was an unexpected relief.

There is no specific gene that we can pinpoint within our family’s DNA to explain the hereditary autoimmune disorders. Autoimmune diseases are incurable, and they remain a mystery to doctors because the root cause is unknown. In 2020, however, breakthrough research linked autoimmune diseases and DNA. According to The Conversation, studies found a common gene called TYK2. Based on research, TYK2 is associated with at least 20 autoimmune diseases. My family has not been tested for this gene. We simply consider ourselves unlucky people with bad genetics.

As Lizette grew up, her body became sicker. She found herself in more doctors’ offices. As a teenager, Lizette was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and Raynaud’s disease. Raynaud’s is a rare disorder of blood vessels in the fingers and toes. The disease causes a person’s blood vessels to narrow when they become cold or stressed. When this happens blood can’t get to the surface of the skin which causes it to turn white or blue. Raynaud’s disease caused Lizette a significant amount of nerve damage to her left foot after surgery to treat her JRA.

While fibromyalgia is not autoimmune-related, it’s still chronic and it causes her a significant amount of pain and tenderness throughout her body. Fibromyalgia is also a mystery disease with no cure. According to research, fibromyalgia and autoimmune diseases almost always come hand in hand.

Lizette understood she was different from the other kids growing up because she was sick. But she did not know how serious her illness was until she was a little older, “Then I realized, “Oh, I have something wrong,” says Lizette. It was a difficult idea for Lizette to grasp. “My doctor told me, ’Your body’s destroying itself’,” says Lizette, “My immune system is supposed to protect me, not hurt me.”

Now, at age 40, Lizette’s sick body is recovering from the virus that almost killed her. Because of her various medical conditions, she was high risk. Lizette doesn’t like to talk much about that because it triggers her PTSD. She does physical therapy to get her lungs back into a healthy state, although they will never be where they once were. Before COVID-19, Lizette would go to the movies to escape the reality of her life as a sick person. “It would take me to a different world for a couple of hours,” she says. Now, three years later, Lizette is too afraid to leave her home as it’s the only thing she says can protect her from the germs of the outside world. “I just prefer it here,” Lizette says. Although, undoubtedly it is the disease that lives within her body that puts her in danger. Lizette enjoys watching movies to pass the time, although it is not quite the same at home. “It’s the only thing that really brings me comfort,” she says. “It is scary when your body does not protect itself,” said Lizette. At this point, I realize that our “quick” fifteen-minute phone call has gone well over an hour. Lizette notices, too, and says, “Well you know what it’s like.” She’s right. I do.

III. Me

I was around 18 years old, sitting on my living room sofa, when I had the worst flare-up of my life. A flare-up is a common term used for the worsening of an autoimmune condition. It’s the exact moment when your body is attacking itself. I gasped for air and it felt like an overwhelming burning sensation was taking over my lungs. I quickly discovered that the only way I could breathe was if I sat up straight. This is how I slept for weeks. On one particularly bad morning, I was watching television when I suddenly had to yawn. For the average person it’s a normal uncontrollable bodily function, but for me it was terrifying. Yawning would require the lung capacity I didn’t have at that time and so would result in a horrible burning sensation that took over my chest. I tried to fight back the yawn, but I was fighting with human nature and my lungs expanded despite my best efforts, triggering the fluid inside of me to engorge my lung walls. It was excruciating and I couldn’t exhale. My body was frozen in time, unable to breathe. Panic overtook me as I went one, two, five, ten seconds without air. My mom, who was sitting beside me, fumbled for the phone to dial 911.

My whole life, I always had this achy feeling in my body. I could never shake it. I would joke with my mom that I was like Vovó. mom would always get angry with me. “Don’t say that!” or “Don’t put that into the universe!” Everyone knew that the maternal side of my family was genetically cursed and that one of us lucky ladies would most likely be diagnosed with something autoimmune-related. But because mom got off scot-free, we figured I would be okay, too. Even before the couch incident, I’d been suffering from bouts of pain in my back and lungs that caused brief seconds of paralyzation. I also was bed-bound to the point where I could not dress myself without mom’s help. We didn’t know what was wrong with me. I became a regular at Brampton Civic Hospital only for them to tell me it was my anxiety or stress making me sick.

I told mom to hang up the phone, and that we would drive to Brampton Civic. This time around we were determined not to leave the hospital until we knew what was going on. I checked into the ER and waited about three hours for a doctor. He was a young doctor, someone we’d never seen before. Right away he could tell something seemed off. He booked me for an X-Ray and several blood tests. Initially, mom and I were hoping it was pneumonia. An hour or so later, the doctor called us over. He appeared concerned. “We are not sure if it is a blood clot or tumor,” he said, “we will have to do further testing.” Everything went black at that moment. I went into a state of shock but tried to remain calm for mom. It was more important to me that she did not feel guilty or blame herself.

I had to do an MRI scan to confirm the doctor’s concerns. The process of waiting and going back and forth with scans took about six hours. When the doctor arrived with the results, he told us it was neither a blood clot nor a tumor, but a hole the size of a penny in my right lung. My body seemed to be attacking my lungs, he explained, causing them to fill up with liquid due to the inflammation. It’s a condition known as pleurisy. The doctor asked us if we had a history of autoimmune diseases in our family. Mom and I looked at each other. “Yes,” she said.

“I felt ashamed telling the rest of the women in my family that I was sick. I was hoping that somehow we had defeated this curse.”

I’ve blocked out most of what happened after that. It is all still a blur and feels like I forever remained in that moment since. I do not regard myself as a sick person even though I am. Everytime my body aches in pain, for a brief moment in time, I forget I am sick. As if there is not a medical bag filled to the brim with pills as an explanation. I used to be really angry and sometimes I still am. I don’t like to think about my diagnosis because it’s too upsetting.

After being diagnosed with pleurisy, I was referred to a rheumatologist in Brampton to figure out what was causing it. Pleurisy doesn’t just happen on its own, it’s caused by an autoimmune illness. So we knew I had one of them, but we didn’t know which. I was not fond of this rheumatologist—After about a month of seeing him, he nonchalantly told me I had lupus. I can’t remember his exact words but he murmured them to me while facing his desktop computer, saying something like, “You’re the patient with lupus, right…” I stared at him blankly and confused. “Me?” I asked, “I have lupus?” He looked back at me and my mom and nodded. “Sorry, I forgot to tell you,” he replied.

Lupus was the illness I was most scared of having because it was the disease that killed my Vovó’s older sister Octavia in 2012. I remember literally praying, Anything but lupus, please, anything but lupus. From what I understood, lupus was an autoimmune illness that causes the immune system to attack itself, which could cause permanent damage to the human body. I eventually learned Octavia had passed away from lupus-related complications, not lupus itself. That information didn’t make me feel any better. My mom was close to Octavia. Her death was hard on everyone. It was my first brush with a death in the family. Little did I know she would die due to complications from a disease that I would later be diagnosed with.

I felt ashamed telling the rest of the women in my family that I was sick. I was hoping that somehow we had defeated this curse. It was all over, I thought, naively. When I told Lizette and Vovó, the pain was overwhelming.

IV. Research

We all dealt with the struggle of having an incurable chronic illness differently. My Vovó drank heavily to deal with her disease or ignored it all together. After years of taking the same medications, her tolerance became strong while her body went weak. Wine helped to soften the blow. In general, the Gouevias don’t deal with pain well. As a family of immigrants, we often abide by the mentality of “don’t ask, don’t tell” when it comes to physical and mental health. We put on a tough face and get back to work like the rest of ’em. Both Lizette and my Vovó find solace in praying to God. That is not something that works for me.

To deal with my diagnosis, I needed to have answers. I needed an explanation as to why this was happening to me and the women in my family. So, following my diagnosis, I began researching whenever I could—meaning, whenever my body allowed me to. I learned that autoimmune diseases arise from environmental and genetic triggers that cause the immune system to attack healthy cells, and there is seemingly no direct cause for them. That infuriated me more. Our bodies were meant to protect us, not fail us. Why was this happening?

To my amazement, Toronto has some of the best autoimmune and lupus research programs in the country. My mom and I decided to leave the clinic in Brampton and asked to be referred to the rheumatologist clinic at Toronto Western Hospital. I was assigned to Dr. Sanchez-Guerrero, a man who’s since changed my life. Dr. Sanchez-Gurrero specializes in lupus and helped me understand why these things were happening to my body. “Lupus has mild, moderate, or severe manifestations,” says Dr. Sanchez-Gurrero. At the time I was on the moderate to severe level.

According to him, it was necessary for me to seek treatment right away. I was prescribed a steroid called prednisone. It’s a drug that lowers the activity of the immune system and slows down the body’s response time to injury. Lizette was also on prednisone. We bonded on how we both had a “moon face,” a side effect of the drug, which caused excess fat to be deposited on our skulls. It was a sick initiation into some morbid club. Vovó took prednisone too in the past but had to stop due to its negative effects on her body. She’s an honorary club member regardless. The prednisone healed the hole in my lung and, for the most part, took the pain away. But not quite all of it. I still had to know why this was happening to my family, and whether this was common in other families.

I spoke to Dr. Nigil Haroon, director of the rheumatology clinic at Western, and asked for some sort of explanation as to why autoimmune diseases happen. Dr. Haroon said, “Autoimmune diseases affect the body in different ways. The symptoms depend on the organ affected and affect the severity of the disease.” He also further explained that there are environmental and genetic triggers that cause autoimmune diseases to happen. One cannot happen without the other.

Essentially, I could have a biological component for an autoimmune disease but if I am in the right environment the disease won’t be triggered. So was it our environment that was making us sick? But what about back in Portugal? Was Vovó’s family sick there, too? We don’t know much about the history of the Gouevias. Mom claims that autoimmune diseases run on the side of her maternal grandfather, Antonio Gouevia and that his sisters had health issues back in Portugal. Vovó says life was different back in São Miguel in the 1950s. If people got sick, they did not go to doctors or get diagnosed. They would drink wine, eat pork, and get back to the farm or fishing boat. So, the medical history of my maternal side of the family is muddled.

“I know it’s not my fault that I have a disease, but it felt like a relief to hear somebody else say it.”

I spoke with Dr. Zahil Touma, a rheumatologist and scientist with the Krembil Research and Schroeder Arthritis institutes. Dr. Touma’s research specializes in lupus, the assessment and clinical measurement of disease activity. “Everything in our life is hereditary,” says Dr. Touma. “There is a higher chance of maybe developing lupus if one of the parents has lupus but there is also a high chance they won’t.” He also clarifies that the same goes for autoimmune diseases. So the answer is: yes but no. They are partially genetic, but mostly it’s the luck of the draw. A sick bingo.

I ask Dr. Touma why women are more impacted. “Nobody knows exactly why,” says Dr. Touma, “But we know the hormonal estrogen and progesterone definitely have something to do with it.” There it was. Estrogen and progesterone, the hormones associated with the female sex, are also the same ones that potentially cause autoimmune diseases. So, Vovó, Lizette, and I really never had a chance. We were all born girls.

Vovó and Lizette are a glimpse of what I could become in the future, and, to be honest, that’s a scary thought. They are happy, but they are suffering. Although the doctors I spoke to were helpful, I wasn’t satisfied. I felt trapped within my own body. I hated it, and I was angry for my Vovó, Octavia, Lizette, Cidilia, and my mom. God did not provide any solace for me because He betrayed my family. I was destined to remain in a body that was failing for life. How could I accept that? How could anybody?

Leanne Mielczarek, the executive director of Lupus Canada, believes in advocating for lupus because it is considered an invisible disease, like most autoimmune diseases. It is usually impossible to look at someone and know they have an autoimmune disease or a disability. More often than not, people with autoimmune diseases appear completely healthy and able-bodied. Mielczarek says, “It is nobody’s fault they have lupus, but we have to ensure there is the proper treatment for the illness.” Those words resonated with me. I know it’s not my fault that I have a disease, but it felt like a relief to hear somebody else say it. It was like a weight off my shoulders. Even my body could not help the DNA it was destined to have.

This made me wonder if there were any other families in Ontario with multigenerational autoimmune diseases. Was this a common reoccurrence? Or was my family the outlier? I got in contact with Kiah Reid, who is the youth-adult group facilitator for Lupus Ontario. Reid says their program sees many multigenerational families who have autoimmune illnesses. “I’d say the most common we see are siblings, typically sisters,” says Reid, “Or parent and child, mothers, and daughters.” Reid also shares with me that she has lupus and so does her mother. I asked her if she knew if it was hereditary. “My mom has had lupus her whole life,” says Reid, “In utero, she made sure I did not have lupus and for two years of my life, I was negative. Then suddenly one day I woke up and had it.” Reid also shares with me that her brother tested for lupus and was negative. It is possible for men to have lupus or any other type of autoimmune illness, however, it is significantly less common. In fact, 80 per cent of those who have autoimmune diseases are women. And when it comes to lupus, the number is 90 per cent.

So my family is clearly not alone in this phenomenon. I was touched by Reid’s willingness to share her story with me. Reid reminds me that there is a larger community out there that suffers from an autoimmune illness like my own. “It is a condition and it does affect you, but your life is not over. You can still accomplish goals, it may just look different from how you originally envisioned it. You can still have a fulfilling life,” says Reid. She’s right, although it may be a bit more difficult than anticipated. Just like Reid and Lizette, I could not outrun my destiny or rather DNA. I, like her, was born a girl to a family where women were sick.

V. Healing

During my research, I came across a book called When the Drummers Were Women: A Spiritual History of Rhythm. Layne Redmond’s book has nothing to do with autoimmune diseases. Rather, it’s a book about women. One quote jumped off the page: “Before we were conceived, we existed in part as an egg in our mother’s ovary. All the eggs a woman will ever carry form in her ovaries while she is a four-month-old fetus in the womb of her mother. This means our cellular life as an egg begins in the womb of our grandmother.”

I felt an overwhelming sense of love for Vovó and the generations of women before her. It may be the body that makes us sick—curses us to years of pain, inflammation, and struggle. But, it’s also the same body that protects, nurtures, and loves us even before our conception. As cliché as it sounds, these diseases exist in my family because the Gouevia women were loved. And the Gouevia women continue to love, even when their bodies are sick and failing them. I put the book aside and decided to call Vovó and see how she was doing. She was having a bad day, so I promised to visit her.

My body, the vessel that carries me, was once a part of Vovó. How could I possibly be angry with our DNA knowing the woman who created it? This means that, no matter what, biologically, my Vovó and I have always been tied. We were women together even when we weren’t. I was always destined to be Esperança’s granddaughter. Nothing can change that fact. It is and always was cemented in history.

“All of the Gouevias share a family bond, a generational trauma, that traverses the bloodline without permission. We all know that we carry a sick gene, something undeniably a part of our past, present, and future.”

The women in my family are strong—all of us. We have seen so many diagnoses, tears, and death. I would have asked Octavia how she dealt with the pain, but I never got the chance. When I tried to bring up Octavia to Vovó, she became visibly upset. I changed the subject and instead asked what made her happy. “You,” said Vovó.

I adore Vovó and love her with all of my heart. I know she feels the same for me. I am her only granddaughter so our bond is extra special, regardless of our illnesses. To be honest, we weren’t close when I was growing up. My relationship with Vovó significantly improved when I was diagnosed with lupus. We developed a mutual understanding for one another. Lizette and I bonded too—nobody truly understands what it’s like to live in a body that is in a constant state of warfare like other survivors. Vovó’s response to my question about what makes her happy prompted me to ask Lizette the same thing. “Yelena, she is my sunshine,” says Lizette. Yelena is Lizette’s niece, who was born right before Lizette was in the hospital with COVID-19. “My niece makes my life worth fighting for,” she says. “I want to be there to see her grow up into a beautiful woman.”

The women in my family are plagued with illnesses that seem to cut their lives short. Octavia never got to see her granddaughter, my second cousin, grow up and become the woman she is today. It is not fair that these uncontrollable things leave irreparable holes in our lives that forever remain empty. All of the Gouevias share a family bond, a generational trauma, that traverses the bloodline without permission. We all know that we carry a sick gene, something undeniably a part of our past, present, and future.

Still, we put on a brave face, maybe not for ourselves, but for the sake of our children and our children’s children. I am not strong because I need to be; I am strong because my mom needs me to be. I am a direct result of cells formed in her body, which in turn formed from DNA that was produced by Vovó when she was a pregnant. Vovó’s body harnessed all the love she had for mom and gave it directly to me—passing down the disease with her.

The same disease was passed down from Cidalia to her daughter Lizette. It is nobody’s fault. We are sick because we were cherished deeply and passionately by the generations of women before us. We are unwell. But my God, are we loved.