Young Women Are Finding Security in the Smutty

BY MARIJA ROBINSON

ART BY CALLIA SILVERTON

———————————————————–

The Romantic Interests of Young Women

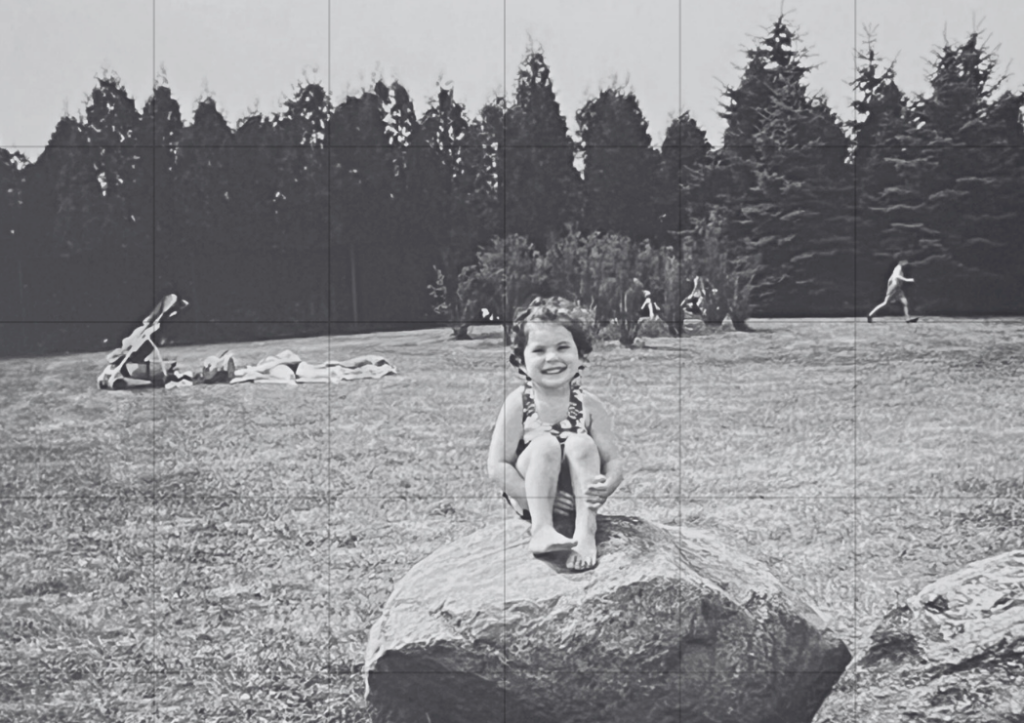

Melissa Michaels’ commute on the Richmond Hill GO train began by locking eyes with a total stranger, an instant attraction, flirty banter, quickening pulses, racing heartbeats, and warm bodies fogging the windows. Buttons opened, and tights rolled down. Privacy didn’t matter.

“. . . It wasn’t long until Cassie whimpered at every thrust. She kept losing rhythm on her clit, too distracted by the gravitational pull in her core, the buildup before a supernova. It was only a matter of time before she exploded. On the brink, Cassie stopped rubbing and pressed hard, her whole body clenching until she broke, shuddering around Erin’s fingers.”

By then, it was time for Michaels to get off—at Union Station. Blushing, she reluctantly stopped reading Meryl Wilsner’s Mistakes Were Made and tucked away her Kobo, heading for the Lakeshore West line to finish her commute. Thankfully, Michaels’ Kobo would be waiting for her on her journey home, where she could return to what Sapphic readers titled the “MILF book.” In it, a young college girl falls for a hot, older woman who also happens to be her best friend’s mom. Mistakes Were Made is just one of many romance books read by Michaels, but regardless of the tropes, characters, or colourful covers, there is one common thread. “Obviously,” she says, “it’s smutty.”

The smut Michaels found in Mistakes Were Made is not rare in the romance genre, reflective of only the most scandalous books tucked away in the back corners of bookstores. Instead, it aligns with what’s happening in most romances, including those piled on the front tables of Indigo. Michaels, a 28-year-old queer Jewish woman living in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), only recently began exploring this world of smutty romance books. Like many young women, she became a devotee of the genre during the pandemic, when attraction to romance novels became a growing phenomenon in the book world.

The year 2022 was one of romance, at least in terms of books. Six of Canada’s ten bestselling books last year were love stories (the number could be seven out of ten depending on your categorization of Colleen Hoover’s Verity). Either way, this figure is higher than any previous numbers since at least 2016, according to BookNet. It likely stretches farther back but the organization, which reports on the Canadian book industry, only began releasing its yearly bestseller lists seven years ago. Admittedly, romance certainly had its moment in the 2010s. The Fifty Shades trilogy comprised Canada’s top three bestselling books of that decade, but even BDSM Master Christian Grey can’t take full credit for the current numbers. Between 2017 to 2022, romance sales in the country increased by 42 per cent, making it the fastest-growing genre last year. Evidently, people are falling in love with romance.

A decade ago, readers aged 35 and over dominated the romance category. But over the last ten years, the market expanded to include those 18 and above. This recent shift in romance readership is not some random occurrence. Young women are driving the rising popularity of romance because of their rekindled desire to find comfort in the guaranteed “happily ever after.” In August of 2022 Statistics Canada reported that, based on over one million responses, nearly 25 per cent of women aged 18 to 34 in 2021 reported feeling stressed most days. In comparison, only 19 per cent of men in that age group felt the same way. While the primary source of their stress is financial, the pandemic hitting at a critical point in their youth exacerbated young women’s feelings of loneliness. They needed to have at least one thing that wasn’t continuously ‘unprecedented’ in their lives. Cue their interest in romance. With its consistent formula and promised happy endings, readers knew what they would get every time. For young women like Michaels, romance became the comforting, mercifully smutty, escape from reality they desperately needed.

The Rules of Romance

The beeps of the fetal monitor tracking the baby’s heartbeat are the only consistent pattern in the hospital room. Moans, occasionally escalating into screams, nurses’ movements, and newborns’ crying, drown out the steady rhythm every so often. Yet, once it quiets down again, the beeps resurface from the machine attached to Ruby Barrett as she prepares to give birth. The author thankfully remembered to pack a book in her hospital bag to soothe her during the acute stress of labour. Specifically, it’s Christina Lauren’s Dirty Rowdy Thing —Barrett’s current favourite.

“My face feels hot, my cheeks flushed. The rope tickles along my skin, pulling up and down in a rhythm that matches the teasing flicks of his tongue. My nipples are hard, aching, and I want his fingers to find them, his mouth to find them. I want him everywhere at once. I feel heavy and desperate, my entire world oriented by where he’s touching me and where he’s not.”

Barrett’s heart rate rises a little, although the fetal monitor has her beat, beeping at its quick, consistent rhythm. She doesn’t get the chance to finish. Things start happening quickly, the baby coming sooner than the characters in her book. But, in those last few moments before her life changed forever, Barrett feels giddy, immersing herself momentarily in the comforting world of a rugged fisherman and his Hollywood love interest.

Barrett knows firsthand people’s need for romance during a stressful time and the importance of a good sex scene. More than that, she knows how to write these stories. Frustrated by her inability to make real people fit together like puzzle pieces, Barrett, a former matchmaker, turned towards writing. Like many authors, she pulls inspiration for her storylines from her life. Barrett uses whatever intrigues her from the books, shows, or podcasts she consumes and works on applying it to her story creation.

Farah Heron, a Toronto-based romance author, does the same. As a South Asian Muslim woman living in Scarborough, Heron intentionally writes characters from her own culture, often setting them in Toronto. She also pulls inspiration from her experiences as an immigrant and from her Asian family dynamics, often using tales passed down from her mom in stories. As with Barrett, being an author was not Heron’s first career. Her turn to romance-writing came in her thirties, when she needed to find a coping mechanism while facing health issues. For both women, their shift from romance-readers to writers resulted from the comfort they found in the genre. Although crafting these stories is hard work, the pleasure Barrett and Heron draw from writing translates to the page, providing a space for young women to escape. Yet, pulling from their personal lives ends with the plot lines.

Before thinking these authors are living the dream, regularly recreating our wildest fantasies, let’s get one thing straight: their relationships do not inspire sex scenes. Instead, Barrett, who has a lot of fun writing these chapters, explains she looks for ideas in acts of everyday intimacy that people often ignore. She notices the way couples act with one another in public—the closeness between them, the little signs that show their attraction towards one another, like leaning in to smell the other’s perfume. It’s about taking these seemingly mundane moments and then asking how that can lead to an orgasm, Barrett says. Yet, a good sex scene is not defined by the resonant sounds of a spank, the breathlessness of getting choked, or the number of orgasms—although authors should include this latter point. It’s all about “the process of escalating vulnerability,” Canadian author Jenny Holiday says. The emotional intimacy during and after a sex scene should drive the plot forward.

Whether it’s a fast or slow burn, a romance must have plotlines and character development beyond the bedroom, kitchen, or backseat of a car. Young female readers agree that having too much of a good thing is possible. Since the genre is entirely about emotions, the characters’ feelings must come first, according to Heron. Everything else, including the smut, is secondary. As romance consistently uses the same storyline of tension, climax (no pun intended), and a happy ending, the formulaic approach provides the essential difference between romance and pure smut, otherwise known as erotica.

Unlike any other genre, romances only have one unwavering rule. “A happily ever after is the only thing that matters,” says Jenny Pool, the owner of the GTA’s only romance bookstore, Happily Ever After Books. She is passionate about this distinction, especially after jokingly arguing on air with a CBC reporter about whether Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is a romance. For those curious, the answer is that for Pool, it isn’t. The heroine’s death puts an unmistakable damper on the happiness of the ending. So, while sex scenes may be a significant draw, it is not the all-important factor in romance, but rather the happily ever after. The promised blissful ending is what differentiates romance from the romantic themes found in fiction and erotica. And this is also what initially sparked young women’s unconditional and irrevocable love for the genre.

The Impacts of Swan and Steele

The split fifth/sixth-grade classroom is quiet for silent reading. A rarity for pre-teens, but anyone daring to whisper faced the penalty of having to leave the room. Teahya Huskins-McDonald looks around at the book covers chosen by her classmates, taking a keen interest in what the older girls are reading. One of them is immersed in a book with a black cover, showing a ghostly white outstretched set of arms with hands cupping a ruby-red apple. Her gaze continues to move. But then something else catches her eye. Another girl is holding that same book and another. Seven girls in her small class are reading this one book. It’s 2008, and 10-year-old Huskins-McDonald missed her invitation to this secretive book club and the adolescent dread of being left out washes over her. The title, though, is somewhat familiar to her, its movie adaptation having just come out. To her delight, her mom, who has the book at home, agrees that if she can finish the book, she can watch the movie. So, Huskins-McDonald immediately starts reading.

“And then his cold marble lips pressed very softly against mine. What neither of us was prepared for was my response. Blood boiled under my skin, burned in my lips. My breath came in a wild gasp. My fingers knotted in his hair, clutching him to me. My lips parted as I breathed in his heady scent.”

With that, Huskins-McDonald instantly joins the phenomenon of young girls launching themselves headfirst into romance by reading Twilight, a love-triangle where the everyday-girl, Bella Swan, is forced to choose between the sullen vampire, Edward Cullen, or the steamy werewolf, Jacob Black.

Although Huskins-McDonald is now 25 years old and living in Toronto with her fiancé, her first experience reading romance reflects those of many women in their twenties, including Michaels. For both girls, Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight was their first taste—or bite—of proper romance, and it happened right at the peak of their adolescence. While the series’ first book came out in 2005, the release of the much-anticipated movie in 2008 triggered the start of the Twilight craze. By the time Breaking Dawn, the final instalment of the series, hit markets in 2008, it sold 1.3 million copies within its first 24 hours of publication. Twilight represented the ultimate love triangle and fit with the intense angst and passions of being a tortured, misunderstood soul—otherwise known as being a teenager. The entire series is a young adult romance and dutifully refrains from the intensely explicit sexual content written in regular romances, as evidenced by earlier excerpts. Yet, however mild, it still provides a certain degree of spice for its younger audience. The Twilight craze became a cultural phenomenon, but its significance extends far beyond introducing teenage girls to romance books.

Teens didn’t just adore Twilight. Adults loved it too—especially E. L. James. Upon reading Twilight, in a desire to expand the stories of the series’ beloved characters, James began writing for Fanfiction.net It’s a space where a book’s most ardent fans write their own fiction based upon that author’s characters, posting it for others to indulge in fresh storylines. After being forcibly removed for overly provocative writing, James created her own website to publish her work, Master of the Universe, without repercussions. The book, once deemed too sexual for online audiences, eventually made its way off the internet and onto bookstore shelves with a new title: Fifty Shades of Grey. The fanfiction-turned-romance series, which charts the relationship between virgin Anastasia Steele and billionaire dominant Christian Grey, put the genre on the map in a way it hadn’t seen for a while—or ever. Fifty Shades of Grey completely changed everything, Pool says. Before its publication in 2011, there were young adult romances, some contemporary romances, and those classic Harlequin mass paperbacks with muscular, shirtless men. Still, the frenzy behind the genre amongst the general population was missing. And then, Fifty Shades of Grey became the best-selling book of the decade in the USA, with more than 125 million copies sold worldwide by 2015. Although undoubtedly smutty—”I’m going to spank you, and then I’m going to fuck you very quick and very hard”—Fifty Shades of Grey is classified as a romance rather than erotica as it follows the all-important rule: the series has a happily ever after.

Granted, many of those teenage girls drawn to Twilight were not the same audience reading Fifty Shades of Grey during the height of its popularity. But, their Twilight youth coincided with this almost inevitable introduction to romance books, at the same time that the genre’s market saw an unprecedented boom because of Fifty Shades of Grey readers. It was the perfect combination for romance’s imminent popularity. Romance had already built itself a future audience at an impressionable age. Those adolescent girls from a decade ago fighting over the merits of gorgeous, glittering Edward Cullen versus strong, sensual Jacob Black grew up. And as they matured, so did their reading tastes. Thanks to the Fifty Shades trilogy, more publishers began to notice the potential of the romance genre, and there was now a market rekindling those interests sparked years earlier.

A Smutty Tradition?

There is a feeling among some of romance’s most enduring and ardent fans that the genre’s apparent takeover of the book industry is an illusion. Their view is that the general population is just catching up, finally recognizing romance as a legitimate genre alongside thrillers, mysteries, and general fiction —esteemed genres that were once traditionally written by men for men. Historically, romance is known to “keep the lights on in publishing because they sell so much more than everything else,” says Holiday. The sentiment directed towards young women is that the industry thrived when your grandma stocked up on Harlequin mass paperbacks, it continued to dominate when your mom discreetly bought a copy of Fifty Shades of Grey, and so your purchase of Colleen Hoover’s It Ends with Us continues an unspoken tradition.

And these dissenters certainly have a point. Women have always loved romance and for a good reason. Polly Beel, who runs the highly successful Toronto-based Instagram account @bettys_book_club, explains that a lot of what women usually consume, especially in their television or film, is through the male gaze. In contrast, romance continues to be written by women for women. Most sex scenes centre on female pleasure, something not typically seen in pop culture, and they happen based on consent, says Holiday. In one of the rare female-dominated industries, romance’s contents are, and always were, revolutionary. It’s no wonder that 82 per cent of romance readers are women. Yet, this renaissance is more than a mere continuation of smutty, womanly tradition.

Sure, women have always loved romance. But not enough to make such a difference in the market—until now. As more young women found themselves attracted to a happily ever after, it changed the business practices within the book industry. If you think you see more romance on the shelves every time you walk into a bookstore, it’s because you do. With this boosted popularity, publishers began acquiring more romances because the genre had proven lucrative, says Jordyn Martinez, who works for Simon & Schuster selling books to big Canadian retailers, including Indigo. This profitable appeal cited by Martinez is particularly true of the last two years. Whereas 2017 to 2020 saw decreases in romance sales, the downward trend ended in 2021 when sales increased by 11 per cent. And 2022 reinforced this, as the sales increased by 54 per cent. It’s no coincidence that the years when the genre took off occurred alongside an extremely unprecedented event. While the Fifty Shades of Grey decade expanded the romance market, earning some attention from publishers, the pandemic blew it open, making it impossible to ignore.

#BookTok is a TikTok subcommunity that focuses on the recommendation and review of books. It’s a space where creators share their favourite reads, and it gained a lot of traction during the lockdown years. The reason relates to Canadian book-buying trends. Compared to 2017, in 2022, 44 per cent more Canadians bought books based on recommendations. So, with 21 per cent of Canadian book buyers on TikTok and the app’s endless stream of book review content, those titles trending on #BookTok equate to rising sales. Point blank, #BookTok books sell. And the most viral books within the subcommunity are romances.

Every title on Canada’s bestselling books in 2022 achieved fame on #BookTok, and yet the formidable romance author Colleen Hoover takes the prize as six of the 10 titles on the list are hers. Hoover’s name has become synonymous with #BookTok virality. And her books continue to sell, much to the amazement of Toronto bookstores. “At a certain point, you’re like, ‘doesn’t everyone have it?” says Rachel Pisani, the store manager at Queen Books. But the romance craze is bigger than Hoover. As other romance authors also found themselves trending on #BookTok, it became clear that the subcommunity changed young people’s reading habits. Whereas before, “light readers,” or the people who prefer formulas in their books, sought out mysteries or thrillers, now they go for romance, explains Pisani. And they can make this transition because #BookTok eliminated the guilt associated with these supposed guilty pleasures. People sharing all sorts of smut on their platforms removed any self-inflicted shame for young women who wanted to rekindle their romantic interests.

An Inclusive Kind of Love

#BookTok was pivotal in the renaissance of romance, but it’s not the sole factor shaping young women’s book-buying habits. Instead, because of the expanding audience, publishers could confidently seek out and invest more resources into new romance authors and their stories, says Martinez. As a result, once the honeymoon phase of virality wears off, what remains is a multitude of options for young women to choose from, enabling readers to branch out beyond the repetitive titles featured on #BookTok. While the subject matter remains relatively stagnant, as there’s only so far the formula can stretch, the authors and characters they create are more diverse, says Martinez. Granted, the traditional conceptions of straight, white couples getting their happily ever afters remain, but they’re now found alongside stories of love reflecting many Canadians’ realities. And this is what keeps readers coming back for more.

Whether through the types of relationships or characters, readers find themselves represented in romance. They can read about people who look like them, or have similar sexual preferences, get their happily ever after—a feature television and film consistently keep out of their reach. For Michaels, this means finally having a space that leaves the uninspired “Bury Your Gays” trope for dead. This common trope, found in shows and movies, is when a queer person, often in a relationship, dies tragically. It enables media outlets to tick off their representation box, giving themselves a pat on the back while simultaneously showing queer people their happiness is unattainable. While the most famous example of “Bury Your Gays” came in the form of Lexa’s death on The 100, the trope also came to life in the shows Orange is the New Black, Game of Thrones, and Supernatural, to name a select few. And while queer people want representation, they’d prefer if the media didn’t consistently pair it with a horrific ending.

Romance ditches “Bury Your Gays,” replacing it with enemies to lovers, second chance romance, fake dating, or marriage of convenience tropes. All of which must have a happily ever after. And this is where the appeal holds for Michaels. She can read same-sex romances without fear someone will tragically die in the end. What a concept! Michaels is also partial to these love stories, as it was through reading Sapphic books that she came to terms with her sexuality. And this appeal of fictional queer love holds for many Canadians, reflecting a significant change in the country’s book industry. LGBTQ+ romances experienced an over 10,000 per cent increase in sales from 2017 to 2022. With publishers devoting more resources to the genre, romance began providing guaranteed happy endings to people whose joy television and film underrepresent.

These guaranteed happy endings aren’t exclusive to queer romances, as characters of every skin colour find love in today’s books. Just as with “Bury Your Gays,” there is a similar trope in the media where the Black character dies first, especially in horror movies. It’s a tiresome pattern, portraying their lives as dispensable, but romance proves itself to be radical once again. As Black and multiracial couples find true love, Canadians support the genre’s evolution. The sales of romance books featuring Black characters rose by over 1,700 per cent from 2017 to 2022. And while some of the books overtly promote the diversity of their characters, showing cartoon versions on their front covers, others play it cool, letting readers discover later what their protagonists look like.

Huskins-McDonald experienced this as she read about the main character, Iris, in Terms and Conditions by Lauren Asher. It took her reading partway through the book to realize that Iris, like her, is Black. “Even though it wasn’t my favourite book,” Huskins-McDonald says, “I felt really connected because of our skin tones.” With the romance genre diversifying, there are many options for young women, enabling romance to keep its growing audience as it captures new readers—especially those joining from #BookTok.

So, as young women experienced the stressors of adulthood, combined with the continuous onslaught of unprecedented pandemic events, they craved escapism. That familiar rush of adrenaline found in former sources of literary comforts, like thrillers and mysteries, became overwhelming, triggering anxiety rather than easing tension. Looking for formulas elsewhere, young women easily found them in romance books, reading about someone like themselves getting their promised blissful ending. There is a lot of pleasure drawn from romance’s formulaic approach, in knowing what you’ll get every time, resorting to the enjoyment they first found with Twilight. Huskins-McDonald and Michaels’s experiences, like for many young women reintroducing themselves to the genre in the last couple of years, demonstrate that it isn’t the sex scenes young women love, although it certainly doesn’t hurt. Instead, it’s that promise of a guaranteed happily ever after.

. . . And They Lived Happily Ever After

The only option to avoid dizziness is lying down. It’s 3 p.m., and Huskins-McDonald is on day four of her week-long quarantine, her entire body weak from fighting off COVID-19. With her head pounding, she puts her phone away, unable to handle her screen’s glare. It’s been three years since she considered herself a reader, but last month she decided to buy Colleen Hoover’s Reminders of Him on a whim. It’s February 2022, and the book is starting to collect dust, but there’s nothing else to do beyond lying in bed. So, she picks it up. She promises to read three chapters before scrolling on TikTok, sure this newfound interest will disappear as quickly as it came.

“He pulls out of me, and when he does, I whimper. It’s an immediate emptiness I wasn’t prepared for. Ledger remains on top of me and slides two fingers inside of me, so I don’t even have to complain before I’m moaning again. He kisses the spot just below my ear. ‘I’m sorry, but I won’t last long when I’m back inside you.'”

It’s midnight. Huskins-McDonald closes the book, having spent the last nine hours reading Reminders of Him in its entirety. She lost herself entirely in the narrative, replacing a pounding headache with a racing heartbeat. For a few hours, Huskins-McDonald found an escape. One that allowed her to return to the nostalgia of her adolescence, with the bonus of smut. She could take a break, leaning into an old, familiar comfort that, despite how awful everything felt right now, someone out there was getting their happy ending—even if it was fictional.