BY LIVIA DYRING

ART BY SAMAN DARA

———————————————————–

On a spring day in southern Iraq, an archaeologist digs with a trowel. Layers of time become piles of sand-coloured soil. Several thousand years down, the archaeologist hits something solid, something that has been shaped—something made by human hands.

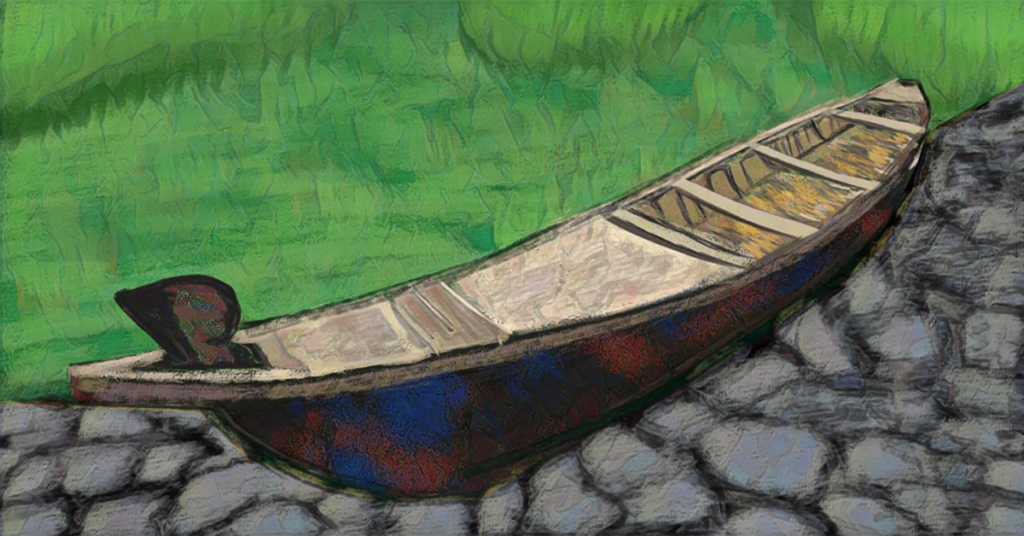

In 2022, archaeologists digging on the dusty grounds of the site of ancient Uruk in southern Iraq, believed to be the first city in the world, came across a boat. When they removed the soil, they discovered a remarkably well-preserved wooden hull. Its narrow and slender shape with two pointy ends made it look like a common canoe—a perfect vessel for travel down smaller waterways.

It seemed identical to the wooden canoes used by the Ma’adan, an ethnic minority population known to the West as the Marsh Arabs. For many generations, the Ma’adan have lived in marshes that stretch across the Euphrates, Tigris, and Karun River delta, some 180 kilometres away. The boat from Uruk, however, was found to be more than 4,000 years old, and was promptly taken to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad for conservation.

It seems peculiar, perhaps, to uncover a boat in a place so bereft of water. But archaeologists working in the southern parts of Iraq are aware that the monochrome, dehydrated landscapes that often surround Middle Eastern archaeological sites could be starkly different from the ancient environment that Mesopotamian cities , such as Uruk, rose from. The discovery of an ancient boat points to an ancient presence of water. The world has long heard about the Tigris and Euphrates, the two grand rivers that flow southwards through Iraq down to the Persian Gulf. The Tigris and Euphrates were used to engineer irrigation canals that supplied otherwise infertile land with water. Uruk was but one of many ancient southern settlements well fed by such a canal system. The rivers and their canals made life in Mesopotamian cities possible — or so the traditional tale goes.

However, archaeologists working today are slowly revealing that southern Mesopotamian society was also founded on an often overlooked water source: vast wetland ecosystems that began to form across what would become Iraq, approximately 7,000 years ago.

A World Built from Water

Every spring heavy rains fall and snow melts off the Taurus Mountains in the north, causing the Euphrates and Tigris to swell. The southern river delta—the meeting point of the Euphrates, Tigris, and Karun rivers— spills over onto the arid plains, filling several mighty bodies of water that linger under the hot sun. Fish travel from the Persian Gulf and water buffalo, birds, and humans flock to the blue oasis to take part in its abundance.

A few years before the four-thousand-year-old boat was found at Uruk, an archaeological team digging at Abu Tbeirah, a southern Mesopotamian site inhabited around 5,000 years ago, made another rare discovery that offered clues about Iraq’s lost wetlands. Mats made from reed stalks or large grasses that grow naturally in wetland ecosystems were found wrapped around the human skeletons from several graves. In a region where metal ore, timber, and stone were scarce, local, natural resources were essential to construct the tools and shelter that humans needed.

The once green and yellow reeds were charcoal gray and would have crumbled upon touch. But once the soil was carefully dusted off, preserved handmade patterns emerged. Like objects fashioned from wood, it’s rare to find artifacts made from reeds, as organic material decays in ways that metal and stone do not. Archaeologists recover things made from earth. Clay was another resource that could be freely gathered from the banks of marshes and, much like plastic, be shaped as much as the maker wanted to.

Clay was used to make drums, whistles, and animal and anthropogenic figurines likely for ritual purposes or children’s play. Most clay objects were made for practical purposes, serving the needs of Mesopotamian households. Housewares, such as vessels and dishes crafted in a variety of sizes and shapes, are some of the most common ancient Mesopotamian discoveries.

What remains of places like Uruk and Abu Tbeirah today may seem like a shadow of the lush green and blue waterscape that once gave life to the first cities in the world. But from the rivers and the marshes sprang a vibrant, coexistent natural and anthropogenic world, whose traditions would last for thousands of years —until later generations of humans would take them to the brink of extinction.

The Time of the Ma’adan

Building a boat for the marshes was both as much work as an artform. A specialist oversaw its construction. The palm trees nearby were softwoods and thus unsuitable, so wood from the acacia or mulberry tree was brought to the marshes from afar. The Ma’adan worked by eye alone to cut, bend, and nail the planks together. When the hull came, the planks were transformed into a seamlessly slender shape with two pointy ends. Then, bitumen—a crude by-product of natural petroleum— was melted down and poured over the bottom to waterproof the vessel. Lastly, the Ma’adan fetched a sturdy reed pole from the nearby reedbeds to punt the boat across the marshes.

In 1968, long after the now-unknown Sumerians paddled the boat over waters near Uruk, American archaeologist and ethnographer Edward Ochsenschlager visited marshlands near the site of ancient Lagash to dig with an archaeological team. The people who live there now routinely build a type of wooden boat — akin to a canoe—that they call a mashoof. The main means of transportation across the lakes, every family must own a mashoof to move around, gather reeds, and tend to their water buffaloes.

The southern Iraqi marshes that Ochsenschlager visited formed 2,000 years ago and are known to Iraqis by their Arab name: the Al-Ahwar. In the 1960s, an estimated 600,000 Ma’adan lived in secluded villages raised on islets across the Hammar, Huwaizah, and Chibayish Marshes, the three enormous marshland clusters that once made up the Al-Ahwar.

For millennia, Mesopotamian cities ebbed and flowed, and the marshland ecosystems that helped support them fluctuated as well. As climatic conditions changed, wetlands shrank and swelled, dependent on temperatures, precipitation, and seasonal floods. They disappeared and reappeared, and the rivers wandered slowly across the vast landscape. Eventually too far away from water, Uruk—the first city—was abandoned. But those who followed the marshes continued to thrive.

The Art of the Reed

Apart from the wood imported to build their mashoofs and a few other objects, Ma’adan traditional craftsmanship was inseparable from the Al-Ahwar and dependent on the same local resources the Mesopotamians gathered from wetlands. To make any reed object, the Ma’adan start by choosing the most suitable stalks. Gliding over the water in their mashoofs, the Ma’adan harvest them and bring them home, turning them into items with a variety of uses, both functional and recreational.

Reed mats require a type of reed called a jiniba, which has grown taller and stronger than others over the course of the year. The jiniba are skinned, split, and peeled before being pounded with mallets to make them pliant enough for pleating. Then, the treated reed stalks are joined together in tight patterns by nimble fingers, a hard and lengthy task that demands sustained focus. Entire houses, musical instruments, cradles for infants, amulets to protect loved ones from malignant spirits, bandages to treat wounds, and mats crafted from reeds—akin to those found wrapped around skeletons at Abu Tbeirah—are made by generations of Ma’adan while the Al-Ahwar thrive.

Once they crumble, a year and a half into their growth, the reeds are used for fuel. In their prime, they lose their gentle green colour and turn yellow or a greyish beige. The Ma’adan judged such thick and sturdy reed specimens—up to nine meters long, gathered from deep within the marshes. Their thickness and sturdiness is what make them optimal to the Ma’adan for the construction of a large mudhif.

Ma’adan mudhifs were grandly arched reed halls, of sorts, that served as guesthouses for travelers and community centres for Al-Ahwar villages. An elaborate type of structure, large ones could reportedly take around three weeks and more than 170 men to build. Enormous amounts of suitable reeds needed to be gathered and tied together in thick bundles before the Ma’adan could carefully bend and secure them together to create their characteristic archways.

It demanded great labour, but to raise and care for a mudhif was to sustain an ancient tradition: a 5,000-year-old cylinder seal from Uruk, now at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, is carved with the image of an elaborate structure constructed from reeds in the same architectural style.

Women’s Knowledge

It is summer, a lifetime away from the cold, rainy season that comes to the marshes in winter. Little children observe women of the village as they dig below the waterline and stuff their satchels with fresh clay. Diligently, they follow them home. They chat happily between themselves, excited they will soon create their own toys from the clay. The traditional craft process they embark on has barely changed over several thousand years.

Before the silty and wet mass takes on a form, the women fortify it with manure or crushed reeds. They proceed to shape it with their hands. Versatile items emerge from the lumps, like a sculpture from a block of stone: the children craft little houses, boats, and wild animals, limited only by their imaginations. The women make vessels, dishes, and containers for everyday use. Once finished, the women sprinkle the shaped objects with water and place them in the shade outside to dry. The next day, they move them out into the sun: the persistent, powerful warmth from the sun rays hardens the clay and makes the objects ready for use. They seldomly break, and when they do, they can easily be repaired.

As Ma’adan men built mashoofs and mudhifs, Ma’adan women had their own cultural knowledge and craft identity that was dependent on them interacting with the marshland. While the Al-Ahwar thrived, women would create their clay objects and care for their family’s water buffaloes and gather reeds. Every adult Ma’adan knew how to pleat a reed mat, but according to Ochsenschlager, only women knew how to make houseware objects from clay.

Though often romanticized by the West as a contender for the Garden of Eden, building a life in the marshes was not simple. “Western sources often romanticize the marshes as the locus of the Biblical Garden of Eden,” says Ariel Ahram, a Virginia Tech professor in government and international affairs. But every object and structure was made from scratch using natural resources, whose abundance depended on the health of the marshland ecosystem.

When the marshes thrived, there were endless materials that regenerated themselves, and generations of Ma’adan men and women continued to build their homes on the water as the Mesopotamians had done long before them. Nobody would have guessed that a type of ecosystem that had lived on for seven millennia—as ancient as the very first cities, and even more resilient, would shrink to comparable puddles in a mere ten years.

A Changing World

A plastic children’s toy in the shape of an animal bobs in the water. Its stark artificial colours stand out against the soft yellows, greens, blues, and browns of the surrounding wetland environment. A petrol motor chugs somewhere in the nearby distance: the soothing sound of the breeze moving through the reedbeds mixes with mechanical noise. Inside Ma’adan homes, now modern breeze-block housing, where clay housewares were the norm only a few years ago, now more durable plastic containers and porcelain dishes have taken their place. On the bottom they read, “Made in China.” In the quiet Al-Ahwar village where little seems to change, modernization arrived.

For several hundred years the Al-Ahwar and Ma’adan culture, for better or worse, evaded modern development. But, from the 1960s onwards, a journey through the marshes on a traditional mashoof showed ominous signs that the natural environment and Ma’adan culture was changing. The use of materials such as plastic, concrete, and steel exploded, allowing humanity to reimagine and remake human life on an enormous scale.

The same progress, however, threatened to throw older cultures founded on natural resources such as stone, reeds, and clay into irrelevancy. Ochsenschlager reported that several thousand-year-old Ma’adan traditions vanished by the 1970s, made redundant by cheaper market alternatives. Such a fate befell reed mats, clay houseware, and the toys made by Ma’adan children, who pleaded with their parents to buy them more colourful plastic alternatives. It became expensive to construct and repair mudhifs, and those that were built seemed smaller than before.

Overall, the unique, exceptionally long-lived Ma’adan crafts culture, became a shameful symbol of poverty and outdatedness. The traditional making of Ma’adan objects and structures dwindled and changed Ma’adan identity along with them.

War in the Marshes

Once abundant canals are replaced by concrete roads. Cars are soon parked along the streets where, not long ago, boats rested calmly in the marshland water. “In the old days, this whole area was covered by water,” Haji Abdun Mehsin told a British Journalist visiting his Ma’adan village in 1987. For generations, Mehsin’s family specialized in building taradas—a large type of mashoof used by the Sheikhs—local Ma’adan rulers of sorts. “There were no roads and no solid buildings. Everybody used boats to get about—all that has changed.”

Due to the 1968 political revolution, when the socialist Ba’ath Party came to power, and the beginning of the war with Iran in 1980, the traditional Ma’adan way of life has slowly disappeared. Now, the town’s local mudhif sits surrounded by dry land, and boats like mashoofs and taradas have become obsolete. Mehsin opened a grocery store, and his two sons, a teacher and a government technician respectively, do not have any reason to learn the ancient ways of the life he grew up with. For archaeologists, a sudden interruption of a specific craft tradition tells a story as much as an abundance. In the 1980s, after a period of sea change, Ma’adan activity in the Al-Ahwar suddenly ceased.

First, the war with Iraq’s neighbouring country, Iran, forced thousands of young Ma’adan to fight. Those who stayed were removed to the outskirts of Basrah and other big cities, separated from the environment and natural resources that underpinned Ma’adan livelihoods and culture. Abandoned Ma’adan villages were burned down. Then, several years after the last Ma’adan family left, the Al-Ahwar were destroyed.

Saddam Hussein, the then-president of Iraq, ordered the marshes to be emptied and converted to agricultural land shortly after the Gulf War ended in 1991. According to the wishes of the Ba’ath Party, the history of Iraq had to be streamlined and unified and minority cultures assimilated. When he came to power, Hussein promptly turned to Western-educated Iraqi academics, including archaeologists and historians, for help with justifying an intensified political crackdown on the marshes. Together with the government, they planned the overhaul of the Al-Ahwar and Ma’adan culture. Villages were bombed, reed beds burned, and water poisoned and drained. In their prime, the Hammar, Chibayish, and Huwaizah Marshes stretched out over an area 20,000 square kilometres large. Ten years later, they were reportedly ninety per cent gone.

Though the loss of the marshes may seem rather sudden, the stage for this ecocide was set for a long time. After World War I, the Iraqi government , supervised by colonial Britain, sought to bring a modern, industrially productive way of life to the Al-Ahwar. Schools and administrative centres appeared on the fringes of the marshes, along with a modern market economy. Around the same time, British, German, and French archaeologists increasingly arrived in Iraq, keen to uncover Biblical remains. Western explorers, such as Wilfred Thesiger, visited the Al-Ahwar, reporting on his stay to British audiences.

While they once lived sheltered by the marshes, the Ma’adan were now on the global public radar, and as state governance encroached upon them, a poor social reputation began to stalk them like a dark cloud. For hundreds of years, the Al-Ahwar provoked state rulers who were suspicious of the natural camouflage of its tall and dense reed beds and frustrated by the biodiverse, vast marshlands that could not support large-scale agriculture.

According to Jaafar Jotheri, geoarcheologist at the University of Al-Qadisiyah in southern Iraq, Saddam Hussein was no different. “The Iraqi government sent Iraqi students to study abroad. They got their Master or PhD degrees from reputable universities ,” says Jotheri. When they came back, Saddam Hussein gathered them and asked them to rewrite Iraqi history in a way that the Hussein government preferred.

The new story promoted by the government in Iraqi media and in schools, as advised by historians and archaeologists, was straightforward: erase all memory of the marshes. “I did all my studying in Iraq. There was nothing in the Iraqi curriculum cherishing the marshes and the Marsh Arabs,” says Jotheri. “When we talked about the geography of Iraq, we mentioned the desert and the mountains, but we barely mentioned the marshes. We did not know about their culture.”

While much was different and beautiful about Ma’adan culture, such as the relative autonomy enjoyed by Ma’adan women compared to women who lived in Iraq’s modern metropolitan cities, this part of Iraq’s history was deliberately not taught in school, Jotheri says. Ma’adan traditional lifeways were seen as an embarrassing obstacle to the ruthlessly efficient agricultural state machine Saddam Hussein wanted to engineer. Seen by the state as foreigners and outsiders who came from abstract, Eastern lands, the Ma’adan had no claim on Iraq’s revered cultural past, says Jotheri.

Their home, the Al-Ahwar, similarly had no relevance in its ancient, supposedly predominant agricultural success story, says Jotheri. The existence of the fruitful, fabled wetlands of Mesopotamian civilization was repressed and forgotten. “You see the game,” he says. “Saddam Hussein barely did his primary school. He had no history or math or science. From where did he get this knowledge? He got it from well-educated advisors. He paid them well and they rewrote history.” The civil war started there, he says, when the academics advised Saddam Hessein and started to divide the larger Iraqi community. “They helped the government in acting against their people.”

For more than a decade after its destruction the Al-Ahwar was a barren desert, until parts of the area were reflooded after the Western invasion of Iraq. Far from all Ma’adan returned, but thousands did. The reeds, the clay, the animals, and the Ma’adan boat-building traditions came back along with the water. As the Al-Ahwar were resurrected, there was once again a home for Ma’adan culture in Iraq.

False Hope

After the end of Hussein’s government, the Al-Ahwar experienced a cultural rejuvenation in addition to its miraculous environmental resurrection: they were reassociated with Iraq’s powerful national pride. They appeared on Iraqi currency, were portrayed as descendants of the revered Mesopotamians who built the first cities partially from marshland resources, and, in 2016, were granted UNESCO heritage status. In a welcome turnaround, the Ma’adan and the Al-Ahwar were no longer despised but cherished .

Before, “It was a shame to be from the marshes,” says Jotheri. “Now, you are proud to be a Marsh Arab.” Even writing about the marshes was once a disgrace, he added, saying that it’s considered a privilege today. However, today and forty years after the Ma’adan were ousted from their marshes by Iraq’s then-government, environmental calamity means they are forced to leave their home behind again.

In many ways, the gradual assimilation into modern Iraqi culture has made things simpler for the Ma’adan. Everyday needs are no longer toiled for in quite the same way — created from scratch and natural resources. But, conversely, Ma’adan identity as a unique ethnic minority is evaporating along with the Al-Ahwar. Ma’adan craft traditions and culture have never been scarcer: its hallmark objects are largely gone, and the skills to make them slowly forgotten. Ma’adan women mostly remain at home, stripped of their identities as skilled craftspeople by the changing environment, their knowledge no longer passed on.

How a Culture Dies

The hot sun shines relentlessly and the ground is cracked and powdery. The warm wind offers little in terms of a cooling breeze. In January 2023, twenty years after the Al-Ahwar were reflooded and brought back from the brink, once well-used mashoof lay stranded on parched land in what was once the wide, sprawling Huwaizah marsh. Outside Al-Chibayish, a town in the nearby Hammar marshes, traditional wooden canoes sit abandoned in a small, polluted pond surrounded by desert. A bony water buffalo sorrowfully stalks its edges. The lush, watery landscape it naturally thrives in seems like a distant dream.

The current climate crisis, projected to hit Iraq harder than most nations on the planet, worsened aridity, and dire scenes of drought have once more become common across the Al-Ahwar. The water from the Tigris and the Euphrates must be diverted towards the big cities, and what precious few oases remain for biodiversity suffer from salinisation and pollution. At the same time, agonizingly slow global action to address climate change keeps worsening the country’s already dire environmental state.

Some describe it as the death of a culture—an ancient way of life decimated by ecological genocide. In spite of a renewed sense of respect for the Ma’adan, not enough has been done to protect the marshes and the rich cultural heritage that depends on them. This will not change, Jotheri believes, saying that Iraq’s Ma’adan culture is “a dying tradition.” The Al-Ahwar are already a casualty of the climate change that now descends on Iraq, and cannot make a full recovery. “Sustainability and celebrating the marshes,” Jotheri says, “is not considered a real possibility.” When somebody suggests reflooding marshes again, he says, “People actually laugh. We don’t have the required water for our cities. Nobody thinks about climate change.”

Everything was destroyed in one decade and whether there will be a reason for mashoofs and taradas to be built again in the Al-Ahwar depends on the willingness to address climate change. For now, the forced pause of Ma’adan lifeways tells a sad story of cultural and ecological death, driven simultaneously by human greed and desire for betterment.

While the world moves towards becoming 1.5 degrees hotter by 2027, our natural environments continue to grapple with widespread change. For as long as there have been cities, there have been wetlands. Now, as the challenge of climate change arrives, Iraq—and what little remains of Ma’adan culture and the ancient Mesopotamian legacy it nurtured—will need to do without them.