Four suicides and four years later, I revisit what happened at the University of Toronto.

BY ALOYSIUS WONG

PHOTOGRAPHY BY ALOYSIUS WONG

———————————————————–

Trigger warning: This article contains discussion of suicide.

The University of Toronto (U of T) is home to more than 95,000 students across its three campuses. They come from Toronto and Brampton; Calgary and Vancouver; London and Boston; Hong Kong and Doha. These students and their professors form a community surpassing the population of Niagara Falls, Ontario, and they delve into everything from diaspora studies to digital humanities to public health and immunology. It is widely regarded as the number-one university in Canada, and has been listed among the top 25 post-secondary institutions across the globe. Here, the finest minds in the world gather to consolidate their knowledge of the past, solve problems of the present, and lead the way into an uncertain future. Its press publishes approximately 180 new books each year. It is a hub of knowledge, a place of innovation, a factory of research. Every day, hundreds of lectures, seminars, and practicals are held. Questions are asked; answers are given. Cutting-edge information and groundbreaking theories find their way into the consciousness of tomorrow’s leaders. This hour is different.

The day is January 30, 2019; it is ten in the morning. Through patches of cloud, the skies are clear and deep blue, not unlike the official crest of the university. In typical circumstances, I would be learning about international relations. But instead, I swap out my usual sweatshirt for a button-up and make my way to the Planetary Observatory of the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. I’m not the only student missing class; as I tentatively enter the main floor area colloquially known as the library, there’s at least fifty, maybe sixty of my peers who have already gathered. There are guests, too—some even from abroad—but no guest lecture today.

Hugs are offered, and knowing condolences exchanged. There’s a donation box for books in the middle of the hallway, already overflowing. I leave one that I had urgently grabbed that morning from my father’s collection.

Today, there is no expert to turn to for answers. Certitude and clarity have taken their leave; doubt, disbelief, bitterness, and bewilderment permeate in their place. A somber understanding punctuates the air, the words yet unspoken ringing in the minds of those present. Carey Davis is dead. She died by suicide.

The Person

Carey was a brilliant person in every sense of the word. Intelligent and hard-working, she was one of the thirty-four first recipients of the Lester B. Pearson International Student Scholarship. According to the university, it’s U of T’s “most prestigious and competitive scholarship for international students” pursuing an undergraduate degree—covering tuition, residence and all incidental fees for four years. She was passionate about effecting social change, participating regularly in climate change activism and raising awareness about all sorts of social justice issues. Her curiosity and drive for truth led her to practice journalism, first by contributing to her high school paper, and later at U of T’s The Varsity. An avid reader and writer, one of her last pieces was an article titled “When Truth Goes to War,” detailing the narrative struggle between Israelis and Palestinians. Published posthumously in that year’s edition of the Rapoport Journal, it was dedicated to her memory. In the short time I knew her, she radiated kindness and thoughtfulness, while demonstrating integrity and a rare care and concern for the world. She challenged and elevated those close to her, and never failed to strengthen the community at large.

As a self-described bibliophile, I wonder if she foresaw the pain her death would cause as her presence left us suddenly and without warning. It was as if a novel had been left unfinished midway through its most important chapters. With nothing resolved, readers were left to speculate about what might have been.

Carey died the night of January 27, 2019. Her death marked the first reported on-campus suicide at U of T that year. But it wasn’t the first the community had endured, and it wouldn’t be the last. Just six months earlier, in June 2018, a student died by suicide at the Bahen Centre for Information Technology. That wasn’t the last death at the Bahen Centre—a second followed in March 2019, and a third in September. Talking to students and staff, these were far from the only ones. Most U of T students live off-campus and commute, and it is unclear whether or not U of T tracks suicides that do not physically occur on its campuses.

Each of these deaths devastated dozens of students and deeply affected hundreds more. It didn’t matter if you knew the person, or even their name. They walked the same halls, ate the same food, took the same classes, then died in the same buildings where we studied and slept. They were one of us; indeed, they could have been any of us. Those four suicides became a rallying point for the student body to demand systemic change. Nearly four years later, many of us would still attest to the lingering impact of those dark days. With the attention and scrutiny it brought to the university in the months that followed, the question still remains whether the fallout led to lasting change—or simply performative damage control.

The Building

The Bahen Centre, at 40 St. George Street, stands out—a modern mid-rise of concrete and glass in a historical downtown campus. This was a place designed for twenty-first century learning. There are about 300 offices, fifty computer labs and ten lecture halls across its eight floors, with a glass ceiling lighting a large open foyer.

It’s frequently busy. Open late to students, the Bahen Centre is often filled with young prospective engineers and computer scientists labouring over a mathematical proof or a programming hurdle. Such was the case on March 17, 2019. With final exams and projects due in just over two weeks, it was cram season—even if it meant long days and even longer nights, the work had to get done.

Ibrahim Hasan, a second-year computer science student, was completing an assignment in the building. It was about 9 p.m. on the evening of March 17 when Hasan left the Bahen Centre to buy a second dinner. He and his friends had an assignment due the next day, and they needed fuel for a few more hours of work. When they came back, the building had been cleared out. An ambulance was posted outside. “I was here literally five minutes ago,” he thought to himself. What happened?

“This just felt really close to me, even though I did not personally know the person. It affected my entire outlook.” — Ibrahim Hasan

He found a friend sitting outside the building across the street sobbing, as others huddled around him. Instantly, he knew what was later confirmed—a student had thrown himself off a platform high up in the building and fallen. Hasan’s friends had heard the impact. “Usually when things go wrong, they’re far away from you.” Hasan tells me, trying to recall how he felt that day. “You recognize that these things are problems and it’s sad, but it’s not personal. You’re annoyed and wish the world could be a better place—but, at the same time, it’s not impacting your day-to-day life.”

“This one,” Hasan continues, “this just felt really close to me, even though I did not personally know the person. It affected my entire outlook and made me realize—hey, we definitely need a change. There are so many things that we could be doing better—both students and the university.”

Paramedics took Hasan’s friend, still distraught, to the ambulance to help him calm down. Hasan and his study group didn’t know what to do after that. They tried to go back to their assignments. They crossed the street and stayed until 1 or 3 a.m. But they couldn’t get anything done. “Of course, all our assignments got extended after,” Hasan says. “But we didn’t know that at the time.”

The Bahen Centre reopened at noon the next day for classes.

The Parents

A few days later, Hasan was volunteering at the Computer Science Student Union (CSSU) office on the second floor of the Bahen Centre. It wasn’t a large room; there was a TV with a selection of games, two tables to study, a refrigerator and shelf with snacks, and the front desk with a volunteer on shift. Often, the space was quite lively, with about a dozen or more students studying or playing games throughout the day. That afternoon, though, it was just Hasan and one other person when a middle-aged couple walked in with a student showing them around.

He wasn’t expecting them, but given the situation, Hasan tells me it seemed like they were the parents who had just lost their son. The student with them had been his friend, and he was showing them the CSSU office where their son had spent some of his time. “I was standing there,” Hasan says, “hoping they don’t ask, but at the same time wondering if I should say something.”

“I felt inadequate in that situation. These parents probably just sent their kid to get a very good education. I’m assuming that they want some sort of closure or something, but I don’t know what I’m supposed to say to them, right?”

Thinking back to that time, Hasan wonders if student leaders like him should be trained for these sorts of situations. “I just know that they aren’t.” He felt helpless that day.

The student said he wanted to honour his friend’s memory by displaying a set of flowers and a letter he wrote in the CSSU. Hasan, of course, wanted to oblige their request, but there wasn’t that much room. He didn’t want to just shove it into the corner—he wanted to show respect. People should be able to read the letter a student wrote for his lost friend. They ended up clearing the top of a shelf in the middle of the room and putting the memorial there. It wasn’t ideal, but it was something.

They left soon afterwards. Hasan didn’t end up saying anything to the family. He couldn’t find the words.

The System

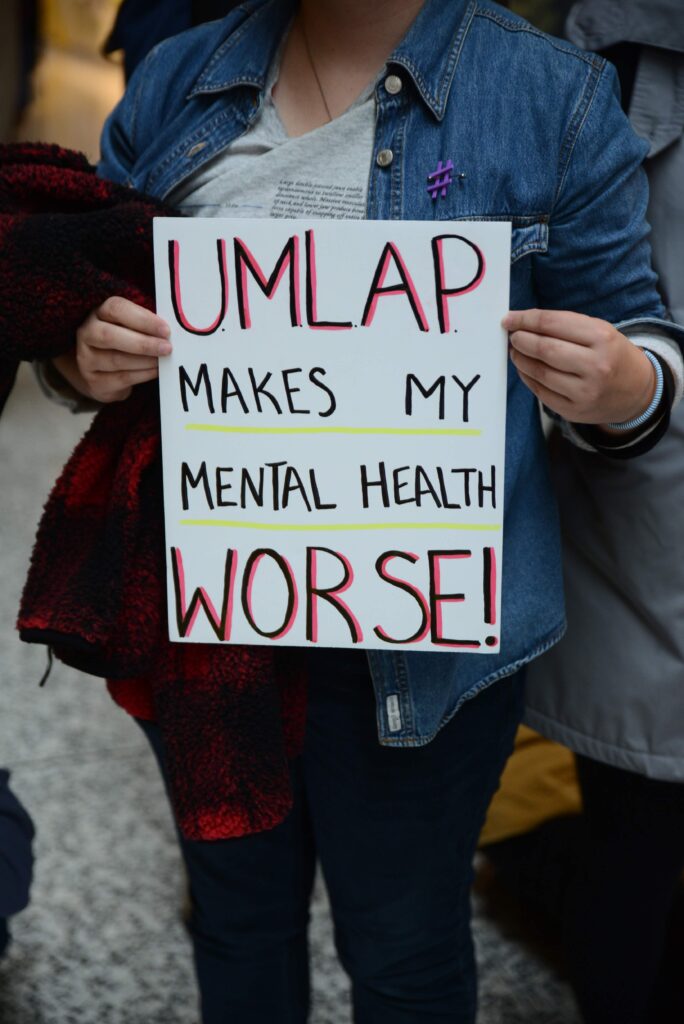

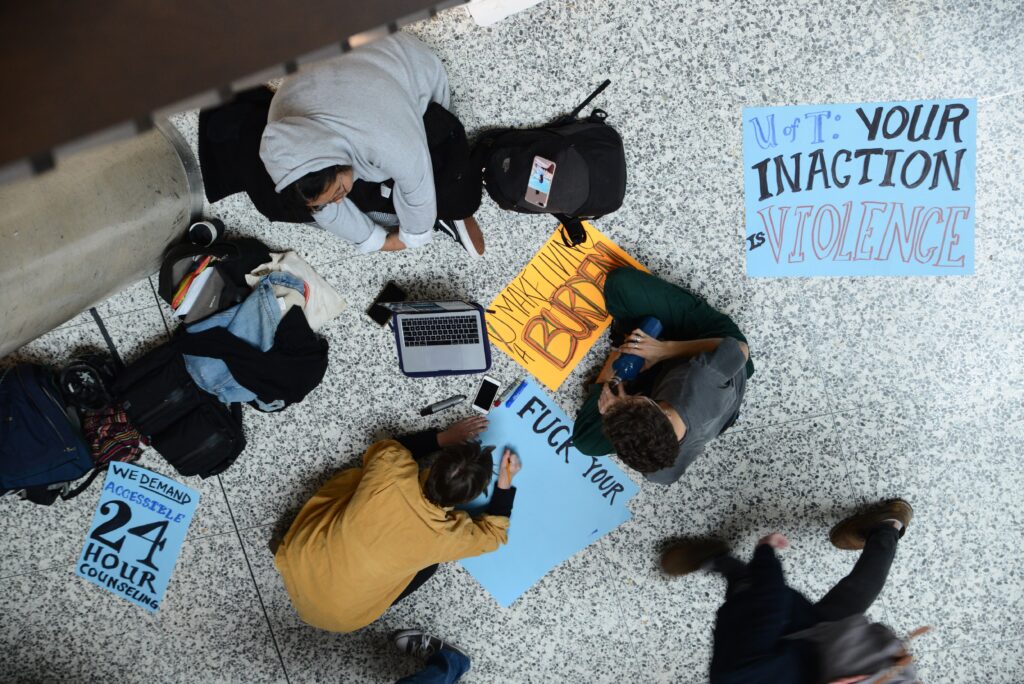

More and more students were finding the series of suicides and the university’s lacklustre response unacceptable. For them, many of whom experienced barriers when accessing mental healthcare at the university, it demonstrated the institution’s apathy toward its students. Student advocates increased the pressure on the university administration, demanding tangible changes. The following Monday, they sat in Simcoe Hall during a meeting of the governing council. Bristol board signs raised common concerns, including shorter wait times for mental healthcare, increased support around high-stress periods such as exam seasons, and more health and wellness staff. Other demands were more specific, such as making twenty-four-hour counselling available and installing physical safety nets at the Bahen Centre.

Catherine Clarke, then a second-year psychology and human biology student, wanted to help. She had lost one of her peers—another U of T student—to suicide just the year prior. Having worked through her own mental health struggles, this was a deeply personal cause. With the hopes of attracting the attention of the university’s governance, she started a petition to U of T and its Health & Wellness Centre to improve student mental health services. She shared it with a friend, expecting at most a hundred signatures. By the time she went to bed that evening, she was excited to see it had sixty-three. When she woke up the next morning, it had 1,400. “I had no idea that there were this many people that were upset by it,” she says. Over the course of several weeks and months, it would grow to become one of the largest civic actions that U of T students and the wider community had taken since 2018. Then, a referendum to implement subsidized student transit pass was held, with nearly 13,000 voters—Clarke’s petition easily doubled that with over 26,000 signatories.

Hello friends! As you’ve heard, a UofT student died by suicide on campus last night. In light of this, and other problems regarding UofT’s (lack of) mental health services, I’ve started a petition to start implementing change. https://t.co/E5Il5y5uIH:https://t.co/MK5j0cFJYa

— Kate (@basicallycathh) March 19, 2019

With several thousand names in hand, Clarke called the office of Janine Robb, executive director of the U of T Health & Wellness Centre, requesting a meeting with her before she contacted the press. Three or four minutes later, Clarke received a call back to schedule a meeting the next day. Their conversation resulted in the creation of a focus group of fifteen students—later named the Health Services Ad-Hoc Student Advisory Group—who would directly advise the Centre on the best ways to address student concerns. It was just one of numerous student groups dedicated to the causes of promoting student mental health and outlining key issues or gaps in care. This included eliminating the annual twenty-appointment cap, ending cancellation fees, and restructuring the website for increased accessibility and resources.

The students later raised concerns about the mandated leave of absence policy instituted in 2018, which allowed the university to place students on involuntary leave should they be deemed a risk to themselves or others. The Ontario Human Rights Commission had already raised concerns that the policy might lead to discrimination and a lack of accommodation for students with mental health disabilities. While we were told repealing or amending this policy was not within the jurisdiction of the Health & Wellness Centre, students stressed that its creation made students nervous about seeking help. International students, especially, were concerned their visas could be suspended if they were no longer actively taking classes.

However, as I quickly discovered during my time as a mental health advocate and student representative, effective changes take time, especially at an institution as large as U of T. Reformatting the Health & Wellness website, for example, required the help and formal approval of the university’s communications team, which delayed the release of the new site for months. In my experience, red tape and the decentralized nature of university services made it challenging to navigate the existing bureaucracy to promote a cause. It was common for each division to have its own personnel, committees, and funding structures. Sometimes, a staff member would know who to forward a request or idea to. Often, they could be as ill-informed of the university’s structure as the students. Envisioning systemic change in such a convoluted system easily becomes daunting.

In the months that followed, some progress was made at various administrative levels. A provostial task force on mental health developed twenty-one recommendations to improve student mental wellbeing, which have been gradually adopted by the university. The computer science program changed its requirements so its students would no longer need above an 80 per cent average in their first-year courses to get in. The university committed an additional $3 million to mental health and launched My Student Support Program, a 24/7 support line for students available in thirty-five languages. The school held conferences dedicated to mental health. Students added mental health officers to their student unions and founded mental health-focused clubs in their immediate communities. But as these programs gradually took root within the institutional and cultural environment of the university, gaps in student care persisted.

The Treatment

The solution for many of these problems seems simple. If you’re ill—mentally or physically—then get treatment. But what happens, exactly, when students do reach out for help? Damien (whose name has been changed due to privacy concerns) is as good an example as any. He had a rough start to his life at U of T. Prior to beginning his studies in September 2018, he had a mental health crisis in Grade 12 and was told he had anxiety. As he began his freshman year, he got what he calls a “pseudo-diagnosis” from a doctor outside the university to help him in his quest for academic accommodation.

Once he went to U of T’s Accessibility Services, he was told to fill out some forms. He asked for help navigating them, but they didn’t have the resources. “Basically, what I was told was, ‘Oh, yeah, here’s the forms. Go fill them out,’” Damien says. At the time, he didn’t have a family doctor or a psychiatrist whom he could go to to fill out the forms. To him, it felt like no one knew what they were doing—inside or outside of the university.

Thankfully, his professors and the registrar’s office helped secure him certain accommodations, even though he hadn’t yet completed the formal documentation. When he finally landed a meeting with an accessibility counsellor at Victoria College during his second semester, it went well. “It was a good first experience,” he says.

This positive outcome turned out to be a one-off event, and Damien says the first semester of his sophomore year was “a fucking complete mess.” He switched programs six times, and was “completely steamrolled” by different professors and departments in the process. One class didn’t accommodate him properly, and another didn’t have lecture slides while the instructor was barely audible. He dropped them both. “I was distraught,” he says, “so I tried to ask for help.” He went to the dean’s office at his college and asked to speak with the campus life coordinator. She was busy.

So, they had him speak with another staff member. “I have never met a man so incompetent in dealing with mental health,” Damien says. “I essentially told him, ‘Hey, man, I really want to kill myself. I have no idea what I’m doing.’ And he said, ‘Do you need a career advisor?’ And I just was like, ‘Are you fucking serious?’ I just sat there listening to him for about an hour. That’s how long he met with me for some reason—without letting me leave.”

The staff member did set up a meeting with the career advisor right then and there, but Damien never showed up. To his credit, he did keep asking for help. He went to one of his friends, who was a commuter don at the time, responsible for improving the experience and overall well being of commuter students at the college. His friend took him back to the dean’s office and got him to meet with the campus life coordinator. She, in turn, took him to the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). The psychiatrists there prescribed a massive up in his medication and the campus life coordinator referred him to a crisis group at the university, which he found helpful. Things seemed to be looking up. Alongside the crisis group, the university also had him begin regular meetings with one of their psychiatrists.

For U of T writ large, though, things were about to get worse—again.

The Fall

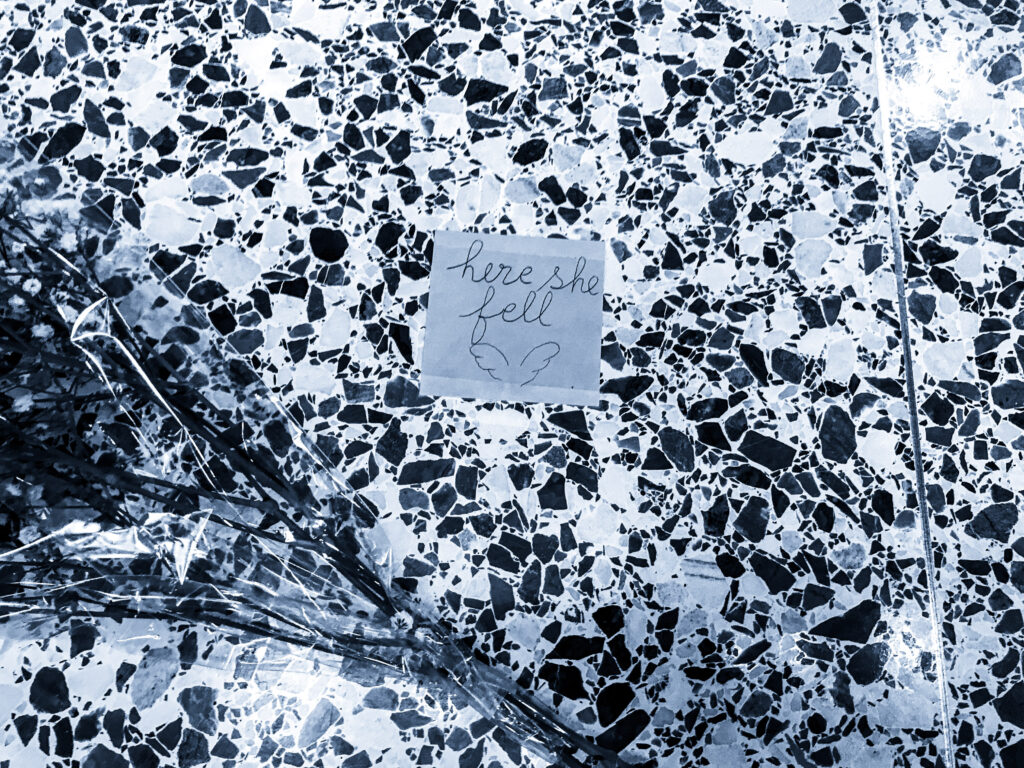

It was September 27th. The 2019–20 academic year was in full swing, and freshmen had begun to find a rhythm to their new life. Midterm season was around the corner, however, and the drop deadline for courses was approaching—a particularly stressful time of year. For Guy Olivier Musafiri, who was homeless and living at Scott Mission near the Bahen Centre and spent much of his time there, it had been a Friday evening like any other. Most students had left the Bahen Centre for the weekend. Musafiri was walking down the stairs to make his way back to Scott Mission when he saw the body of a young woman on the ground. The building was otherwise empty, except for a young man on the phone with a few of his peers standing several feet from the body. “I saw the body, but at the time it was just an injured person in need of assistance,” he says. “That’s what I was thinking—maybe she broke her leg. And I was thinking it was an accident. Something happened and she fell.”

There wasn’t panic. Nothing stood out. Otherwise, Musafiri describes it as a quiet and peaceful evening. “But, thinking back, why would she be so quiet? If she broke an ankle, why would she be still?” he says. There was no blood, no commotion. “Everything looked like it was fine,” he says. “Which probably was also what was wrong in her life. She was in distress, but she did not receive any help. I’m guessing that on the surface things looked normal. Even at the time of her death, everything looked normal,” he says with a dark laugh. “It saddens me.”

He tells me about the events of that night in a café not far from campus. As he recalled it over two years later, he suddenly took off his glasses, furrowed his brow, and let the silence sink in for a few moments. “To be honest with you, I’m angry,” he says, finally. “If everything looked normal but someone died in extreme pain, something terribly wrong is going on.”

The weekend after the death, the third on-campus suicide of that year, the university erected temporary physical barriers at the Bahen Centre. Now permanent, a large metal sheet with small circular holes blocks the view—and the danger—from the fourth to eighth floors. But it was too little, too late. Many students felt betrayed that this exact barrier, which they had spent months advocating for, was implemented by the administration over just two days. It felt like this death was preventable. What if the barriers had been up even a week earlier? One 2016 South Korean study found that nearly half of suicide attempts leading to hospitalizations were the result of sudden inclinations, even if subjects were otherwise experiencing low-intensity suicidal ideation. Young people were particularly likely to attempt suicide impulsively. Given these findings, it seems that a simple change, like a physical obstacle, might go a long way in averting a suicide attempt.

Some evidence for this can be found within the broader history of Toronto. The Prince Edward Viaduct System, commonly referred to as the Bloor Viaduct, used to be the second deadliest suicide bridge in the world, surpassed only by the Golden Gate Bridge. But after 2003, when the city implemented the Luminous Veil, an architecturally artistic barrier around the bridge, the number reduced drastically, though not immediately. A 2010 study in the journal The BMJ found that, while the barrier prevented all suicides from that particular bridge, the overall rate of suicide by jumping in Toronto remained unchanged. But a later 2017 study in the same journal revisited the case with additional data, and found that the Luminous Veil had, in fact, reduced the number of suicides by jumping, without any increase in deaths by other means. The physical barrier didn’t, of course, solve suicidal ideation or mental distress, but it did seem to force those sudden and powerful pulls of the void to pass.

The Administration

In the years since 2019, the grief and anxiety shifted from the mental health crisis to managing remote learning and student supports amid a global pandemic—and then relearning how to adjust back. However, when revisiting the administration’s follow-up since 2019, it is still difficult to get concrete answers on what has tangibly changed for students accessing mental healthcare on campus. The Otter submitted multiple requests for interviews with the Health & Wellness Centre and their oversight body, the Office of the Vice-Provost, Students, which a representative for the university declined “with gratitude.” While they did not directly answer our inquiry as to how many of the twenty-one provostial recommendations have been implemented, a spokesperson told The Varsity in October 2022 that “80 per cent of the task force’s recommendations have been implemented, including same or next-day in-person and virtual counselling appointments at campus health and wellness centres.”

“In line with recommendations provided by the Review Committee on the Role of Campus Safety, the University is working to improve Campus Safety’s approach to students in mental health crises.” https://t.co/zYLkjJFunf

— The Varsity (@TheVarsity) November 4, 2022

In an email to The Otter, the university’s media relations team pointed to an online navigation tool that is now in place to help students connect with relevant mental health services. They wrote that OHIP is the primary care provider for students in Ontario, while the University Health Insurance Plan allows international students to access this coverage as well. The email also highlighted that students are required to have private health insurance for mental health, whether through their families or their student union. (Undergraduate students at the St. George campus, for example, are covered by the University of Toronto Students’ Union for fifteen visits per year for private mental health counseling, up to $100 each).

But merely outsourcing the responsibility of care is insufficient. Seventy-five per cent of mental health problems are established by the age of 24, and suicide remains the second leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 24. Meanwhile, the Canadian Mental Health Association reported in 2020 that the average wait time for counselling and therapy in Ontario is sixty-seven days, with some waiting as long as two and a half years for care. For many students, on-campus counselling and mental healthcare remains the most accessible and viable option. And every day that institutions shift blame and responsibility between their departments, instead of working towards solutions, is another day that another young person seeking help can fall through the cracks.

The Memory

“She wanted to scream, she wanted tears to tear down her cheeks in red fury, she wanted the ice of the railing, the softness of lips, the wonder of a mind ignited by curiosity, the audacity to question, the swelling heart transcended, the tracing of delicate touches, she wanted to feel. But there was nothing. Less than that,” reads an excerpt from a short story Carey wrote and published on Medium. “How enticing Nothing is.”

These words haunted me. I read her story months later, and wondered if that had been a sign, a cry for help, or if it was just part of the story. I replayed every interaction I’d had with her, trying to find clues, desperately needing answers. But I hadn’t known her that for that long, or that well—what did I know? I had had the privilege of being perhaps a good acquaintance over the few weeks when we had been in the same program. We had spoken to our professor together once after the first class, and we’d had the occasional conversation since. She had served me coffee once at Caffiends and we had caught up briefly. That was it. That was the last time I saw her.

“She’d be in awe of her classmates’ projects and successes.” — Cheryl Davis, Carey’s mother

Looking back, I can now acknowledge that Carey’s death had affected me much more than I recognized at the time. I told myself then that I should be able to carry on as before. But after Carey’s death and the sudden heart attack of another friend, I was a ball of righteous anger, grief and confusion. Returning to any sort of normalcy was impossible. I directed that energy into helping organize the rallies outside Simcoe Hall. I joined the advisory group Clarke founded, and whenever I had the opportunity, I tried to alert staff and faculty to the cause of student mental health. I reached out to friends in a panic, paranoid that if I didn’t, something terrible would happen again. Yet, nothing seemed to quite be enough, and by the end of the fall term I burnt out, going from doing everything to struggling to do anything at all.

Everywhere I went there seemed to be some connection to her. Fellow environmental justice advocates remembered her spirit and contributions to the movement. The staff at Caffiends set up a small memorial with tributes from the community. Carey, during her time contributing to The Varsity, had even interviewed Jo-Ann Davis (no relation) about running as a Liberal candidate in the 2018 Ontario election. A year later, at the victory celebration for Chrystia Freeland’s reelection, I saw Jo-Ann again and remembered Carey’s article. I broke the news to her. Her face sunk. So much for a night of celebration.

When people shared memories of Carey that were new to me, it was bittersweet. I could feel closer to her memory, but at the price of knowing more about how much she meant to the people in her life. How unnecessary and avoidable it all felt. If she could bring so many people together in death, I wonder how many she would have united had she lived.

After Carey passed away, her family set up a non-profit in her memory called The Carey Projects. It carries on Carey’s legacy by supporting suicide awareness and education, as well as funding University of Toronto undergraduate student teams that propose solutions to systemic global issues. Their goal is to support one project each year from the university’s Munk One program—an integral part of Carey’s first-year experience at U of T—with guidance and added implementation from Audacious Futures, a social innovation–minded consultancy firm that Carey worked for. To date, they’ve received about over $87,000 in donations, which has funded two projects so far, including an initiative to ease water scarcity in Ihuanco, Peru.

☁️ The AWA Project (founded by Munk One alumni) uses fog-harvesting nets to provide water in Ihuanco, Peru. They received support from The Carey Projects to make the idea a reality! See more in this @munkschool blog post. #mymunkone https://t.co/1GiP4dwhL5

— Munk One (@mymunkone) January 14, 2022

“The importance to us in supporting these students is multifaceted. It’s a way to honour Carey’s passion of social justice in communities of need, sustainable environmental solutions, as well as a way for us to support projects that she would have potentially been a part of implementing,” Carey’s mother, Cheryl Davis, said in an email. “I can assure you, she’d be in awe of her classmates’ projects and successes.”

It has now been four years since Carey died. For me and many others, it feels like a lifetime ago. Clarke is going to medical school at McMaster University, having completed her degree in psychology and human biology. Hasan graduated and landed a job as a software engineer in New York City. I’m now completing my master’s in journalism—an interest Carey and I both shared.

“No institution should be so stubborn that they only work toward change when one of its own dies. No life lesson is worth a life.”

After that fall, I finally sought out professional help to work through my grief. Over the next year and a half until graduation, I met with a therapist and worked through the regret of choices not made, the guilt of surviving while others didn’t, and the discomfort of having questions that will never have satisfying answers. Certain memories can still bring back the pain and loss—things never simply go back to the way they were before. But there’s now a distance, and a sense that this is all firmly in my past, not my present.

I’ve grown. But only because I had to. No one should have to lose a loved one just to be reminded to cherish their friends and family. No institution should be so stubborn that they only work toward change when one of its own dies. No life lesson is worth a life.

The Sky

With pandemic restrictions eased, students are back on campus. A sense of normalcy and familiarity is returning to the university’s ivory towers. It’s almost as if nothing has changed. The sky is blue. Residences are full. Meal halls are crammed with trays of food and exam stress. Every hour, thousands of students shuffle from classroom to classroom. They debate the intricacies of epistemology, bioinformatics, and dark energy as they rush from Spadina to Bay, Bloor to College in the ten minutes between classes.

Lectures and tutorials are back in the Bahen Centre, and people walk past the spot where the young person died, the note Musafiri placed to mark it long gone. The memorial Hasan helped set up in the CSSU office has been cleared, as have the tributes students made for Carey in Caffiends. The halls are sanitized, free from germs, aerosols, and their own history. The rooms where the dead ate, slept, laughed, and cried have new tenants, largely unaware of the stories of those who came before.

———————————————————–

If you or someone you know is in distress, there is help available. You can contact:

- Canada Suicide Prevention Service phone available 24/7 at 1-833-456-4566 (call) | 45645 (text, 4 p.m. to midnight ET only) talksuicide.ca/parlonssuicide.ca

- Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868 | Live Chat counselling at www.kidshelpphone.ca

- Good2Talk Student Helpline at 1-866-925-5454 (call) | 686868 (text “GOOD2TALKON”)

- Ontario Mental Health Helpline at 1-866-531-2600

- Gerstein Centre Crisis Line available 24/7 at 416-929-5200

- Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention: Find a 24-hour crisis centre

For non-immediate care, students can also access on-campus supports:

- University of Toronto students can access on-campus mental health services by contacting the U of T Health & Wellness Centre at 416-978-8030 (select option #5), or emailing mentalhealth@utoronto.ca

- Toronto Metropolitan University students can access on-campus counselling by calling 416-979-5195 or emailing csdc@torontomu.ca

More information about The Carey Projects can be found here.

Many people interviewed for this piece were friends, colleagues, or acquaintances from my time as a student at the University of Toronto.