BY TAREK TAHAN

ART BY S35

———————————————————–

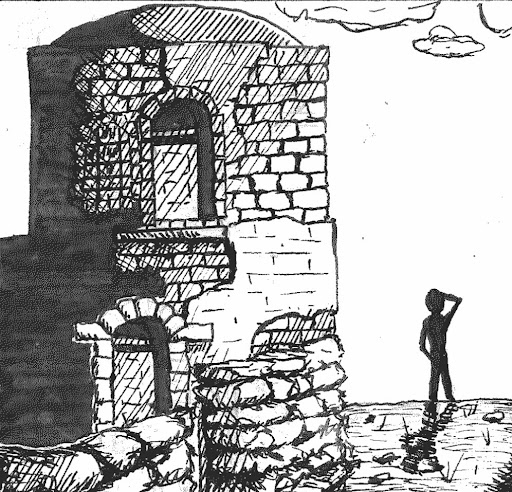

Four generations ago, my grandparents were displaced during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. None of my family has been able to permanently return, and few have even visited. My grandparents fled to Lebanon by foot, where they faced an entirely different form of institutional and social exclusion as Palestinians. To add to their struggle, the subsequent 15 years of the devastating Lebanese Civil War left both physical and psychological scars. In the 1980s, my dad and a few of my uncles found themselves in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, making a living building oil tankers.

My Journey to Canada

Fast forward 20 years to August 20, 2000. I was born in Jeddah, as was my brother three years prior, and my sister three years later. Year by year, the future looked dimmer. The travel document for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon effectively left my family stateless, since Saudi passports are usually not granted to foreigners. One of my uncles once called the travel document for Palestinian refugees a “useless piece of plastic” because of how difficult the document made international travel.

When I was 6 years old, my family and I immigrated to Canada from Lebanon during the second Lebanon–Israel war. My mom recalls us crossing into Damascus, Syria’s capital, and lining up for hours at the Canadian embassy just to get our visas and paperwork processed. She recalled how the woman working at the embassy sneered at my mom’s accented English. My mom replied, “Canada is known as a country of immigrants, is it not?” The lady fell silent. We took the next plane to Cyprus, where we stayed at one of my uncle’s summer villas before flying to Newark International Airport in New Jersey.

We stayed at my aunt’s home in New Jersey, before crossing into Canada and arriving at a Motel 6 in Mississauga. One of my earliest memories was celebrating my sixth birthday at Chuck E. Cheese down the street. Although I was young at the time, this place was distinctly different from the Middle East. For one, the landscape was unlike anything I’d seen before. Back then, I remember Mississauga having a lot more forest and a lot fewer skyscrapers. What was developed was well-polished, lacking the layers of history found in the Middle East. But the biggest culture shock was the society. My surroundings and social circles were smaller and overwhelmingly white.

In the Middle East, racism and discrimination were normalized and overt. The post-1960s movement toward racial equality in North America seemed to have skipped the Middle East. Growing up, it wasn’t uncommon to overhear schoolchildren speaking disparagingly of their housekeepers, usually of Philippine, central and east African, or South Asian descent.

“Growing up, I had trouble pinpointing the central elements of Canadian culture…There’s an understanding that almost every Canadian’s ancestors came from outside North America.”

Meanwhile, in Mississauga, it appeared that everyone treated each other with dignity and respect. I remember being shocked that I was playing with South Asian, Chinese, Filipino, Polish, Croatian, Lebanese, English, and Irish kids at recess and having lunch together. While I had always heard of the stereotype that Canadians are polite, as evidenced by our love for apologizing, it felt especially true when I first came here. We are so polite that I initially thought racism in Canada did not exist. But racism does exist here, it’s just latent. I always felt the Middle Eastern part of me was inferior in my Canadian surroundings. I felt compelled to conform to this home and forsake my other homes. Direct racism, however, manifested itself only when students shouted ‘Allahu Akbar’ at me in the school playground, or when I was pulled aside, at only 10 years old, during an airport security check at Orlando International Airport when returning from a Disney World family vacation.

My Journey to Allyship

In Grade 4, my family and I went out to the Applebees down the street from St. Xavier Church to celebrate my first communion. While everyone dove into the nachos and spinach dip, I was distracted by the posters around the restaurant depicting Westerners alongside exaggerated portrayals of Apache warriors. When I asked my dad who those people were, he explained that they were Indigenous people but that I’d never seen them because they weren’t around anymore.

They were the same people I was learning about in school. In grade school I was taught about how Europeans came to Canada and started the Hudson’s Bay Company, trading furs and weapons with the Iroquoians and Algonquins. Although we took field trips to reconstructed longhouses and learned about many Indigenous customs, the impression I got was that Indigenous peoples only existed in folkloric legends and magically vanished long before anyone could remember. At the same time, I remember reading Indigenous names such as Hurontario, Huron Park, and the name of my city itself: Mississauga.

When my dad told me that the Indigenous peoples of North America weren’t around anymore, I didn’t understand him. I hadn’t yet realized that the Canadian school system glossed over this country’s national shame: the spreading of Old-World diseases that decimated entire populations, the true extent of abuse at residential schools, and the almost complete erasure of millennia-old cultures. For a long time, it flew right past me—a kid who was preoccupied with what it meant to be ‘Canadian.’

Growing up, I had trouble pinpointing the central elements of Canadian culture. I once asked a friend’s parents about what foods were distinctly Canadian and their reply was “maple bacon.” There’s an understanding that almost every Canadian’s ancestors came from outside North America.

Developing this understanding also meant learning some unwritten social rules, the big one being that you can’t just ask people, “Where are you from?” I tried that once with a classmate who was visibly racialized. It was a common question back in the Middle East, but he was confused by my question and responded by saying that he was born here. My mom later informed me it was rude to ask questions like that because here everyone is Canadian.

A Watershed Moment

As I conformed to Canadian culture, I began feeling disconnected from my first home. My parents made sure we visited extended family back in Lebanon each summer, but I had developed an internalized dislike towards our ancestral lands. It didn’t have the same polished look I’d grown accustomed to in Mississauga. For me, Lebanon had become inferior to Canada. While visiting, I would constantly complain about the lack of running electricity, the lack of traffic laws, and the high levels of poverty.

“The Wendat were the first to settle in what is now the Greater Toronto Area—before the Senecas, the Mississaugas, and global immigrants.”

The Palestinian and Lebanese aspects of my identity only began to cement at the end of my Grade 9 year, in 2014. In July of that year, while visiting Athens, I watched newsreels on television of airstrikes destroying buildings in Gaza. I asked my dad and uncles what was happening. “Israelis are attacking us again, with an American blessing,” said Uncle Hani. Later that night I opened up my dad’s computer and typed into the Google search bar: “What is happening in Gaza?” Little did I know, I would fall down a rabbit hole of YouTube videos explaining how Palestinians lost their lands. That following September, my research into Palestinian history began to grow as celebrities started to speak up. When I travelled back to Beirut during the summer of 2015, I asked my grandmother, “Why did you leave?” Every time, she would fall short of answering, shaking her head and only softly murmuring in Arabic, “We had no other choice.”

Unlearning

Throughout the rest of high school and into university, I regularly attended cultural events to learn more about Palestine. In January 2020, when I was in my second year at the University of Toronto Mississauga, I attended a Canadian politics lecture where the professor assigned us an essay. We had to write on either the 1970 October hostage crisis in Quebec carried out by the Quebec Liberation Front or the recent Wet’suwet’en protests. I chose the latter.

In my research, I found a photo of mini-Palestinian flags fluttering alongside Wet’suwet’en flags at railroad blockades, even though there was not a single Palestinian at the protest. Suddenly, it felt like my Palestinian identity had found a connection. Palestinian and Indigenous peoples share an understanding of forcible separation from their land and cultural practices. So, seeing our flags at the Wet’suwet’en protests wasn’t as strange as I first thought. “Folks who have come from other places in the world are working alongside us,” says Amy Desjarlais Waabishka Kakaki Zhaawshko Shkeezhgokwean (White Raven Woman with Turquoise Eyes) who is Ojibway and Potowotomi from Wasauksing First Nation.

Despite the COVID-19-induced closures, my family and I took a road trip to the Six Nations Reserve. I called a gift shop to see if it was open, but the lady told me they had to close for several hours because they were waiting for hydro. As we drove past the remote trailer houses and log cabin smoke shops, it felt like I was driving through an impoverished country. It was unlike anything I’d seen in Canada. The clerk at a hunting store and I had a brief conversation, where she told me that both her parents were residential school survivors. I fell wide-eyed and silent.

Later that night at home, I entered “settler colonialism” into Google. Surprisingly, several other countries besides Canada popped up, such as Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Israel, the US, Russia, Ireland, and parts of Japan and Scandinavia. I also searched, “how to support Indigenous people.” Among the results were the names of several small businesses, including one called Beaded Dreams. Two weeks later, I had a dream catcher hanging in my room.

Immersion into Indigenous Cultures

Following the summer of 2020, I was inspired to learn new languages while watching people on YouTube effortlessly master dozens of languages. Feeling indebted to the inhabitants of my Canadian home, I decided to learn an Indigenous language spoken in Canada. I considered Cree, Anishinaabemowin, and the Six Nations languages of Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora, before choosing Wendat.

I chose it because the Wendat are considered to be the original inhabitants from Lake Ontario’s northern shore to Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay. The Wendat were the first to settle in what is now the Greater Toronto Area—before the Senecas, the Mississaugas, and global immigrants. In learning the Wendat language, I relied mostly on dictionaries written by French missionaries in the seventeenth century as the language had gone nearly extinct around the mid-eighteenth century.

Without any fluent speakers around, my practice remains limited to talking to my dog, Gucci. However, in trying to show my solidarity, I’ve made mistakes. I once called a Wendat cultural centre in Quebec to register for online language revival classes, but the secretary told me that the classes were reserved for Wendat. In May 2022, I was given membership to one Indigenous centre in Toronto, only to be revoked. When I asked the head of the centre why he did that without warning he replied sternly, “The centre was for natives of Turtle Island only.”

While learning the language, I searched for someone from the Wendat community in Canada who would be willing to speak with me. It took weeks of back-and-forth email exchanges with the band council office in Wendake Reserve near Quebec City, which is the only one in Canada, to find researcher Jean Phillipe Thivierge. He was skeptical of my efforts, saying, “You don’t have any sort of obligation to speak the language. It is our path to go through.” He suggested that before trying to learn Wendat, I must first focus on learning about the Wendat culture and modern history. Thivierge also mentioned how the language is meant for the Wendat, rather than being something for anyone to master. He explains, that I am trying to master his ancestral language without ever having met a Wendat person. “It’s too much, too soon,” Thivierge said. “Go baby steps, but don’t try to be more Wendat than the Wendat themselves—that’s not your duty.”

“Learning to adapt to different environments forced Dabat to pick and choose which cultural traditions to hold on to and which to abandon, but he eventually learned to balance the two.”

These barriers were frustrating at the time, but I now understand the importance of allowing Indigenous people to exercise their right to govern Indigenous spaces and language. It reminds me of my family dealing with my grandparents’ displacement from their village of Al Bassa during the Arab–Israeli war, and the denial of their right to return.

Defining Home

My father once told me that he grew up watching Westerns. But he and his brothers would sympathize with the Indigenous, who were portrayed as villains, over the cowboys because of our Palestinian history of oppression. It seems like just as it was for my father, engaging in solidarity work with Indigenous people was a way for us to bond with our new home and escape the stigma of feeling like outsiders. I tried explaining this feeling to a friend once, but they didn’t understand what I meant. I was saying that my people and Indigenous people have both felt like outsiders in their homes.

My dad and I aren’t the only ones I know of who have felt this way. My brother’s friend, Wissam Geahchan, who is a Lebanese-Palestinian-Canadian, moved to Canada in 2006 when he was 9 years old. Geahchan and I agree that we feel more accepted and welcome in diverse cities like Toronto.

Just a few months ago Geahchan was in Weyburn, Saskatchewan. While in a bar, the waitress bantered, “You are not from around here, are you?” When he asked her what made her suspect that, she said, “Well, you don’t have the pale white skin we do.” Geahchan said to her, “This is Canada. We are all Canadians, but at some point, we all came from somewhere.”

When talking to me, Geahchan said, “I kind of sit in the middle. I am not white enough here, and there, we’re not Middle Eastern enough.” There’s also our family friend, Jadd Dabat, a Palestinian activist who has worked with First Nations communities. While he was born in the US, he split his life between Saudi Arabia and Canada intermittently from the early 1990s until he settled in Canada permanently in 2016 to pursue his post-secondary studies. He continues to visit his parents’ hometown of Hebron on the West Bank of the Jordan whenever he can. “When you’re shifting between different countries, your definition of home keeps changing,” Dabat says. I understand that. Moving through several countries before coming to Canada meant that I kept changing my definition of home, too.

Learning to adapt to different environments forced Dabat to pick and choose which cultural traditions to hold on to and which to abandon, but he eventually learned to balance the two. Over time, Canada felt more like home to him, but there were still certain things to come to terms with, including the fact that he currently lives on the Wendat and other Indigenous people’s ancestral homelands.

Discovering what Indigenous people experience on reserves throughout Canada motivated Dabat in third year at the University of Toronto to reach out to Indigenous groups and organize solidarity panels. The panels discussed socio-economic inequalities, such as drinking-water advisories in First Nation and Inuit communities across Canada, and restrictions on free movement for Palestinians. Dabat says his main takeaway from organizing these panels is that when oppressed people form alliances, it can be mutually beneficial. “It’s power in numbers at the end of the day,” he says. “You feel that you’re not alone.”

While I am forever thankful to Canada for providing my family with a safe place to call home and an escape from potentially perennial statelessness, learning the history of Indigenous people in Canada made me feel complicit in settler colonialism. I learned that what I was doing to Indigenous people was what was done to my grandparents. Reconciling these realities—and my identities—has been difficult, and I’ve stumbled along the way. But, I’m committed to learning the history of my new home.