My best friend left Mormonism

BY SAM JABRI-PICKETT

ART BY CALLIA SILVERTON

———————————————————–

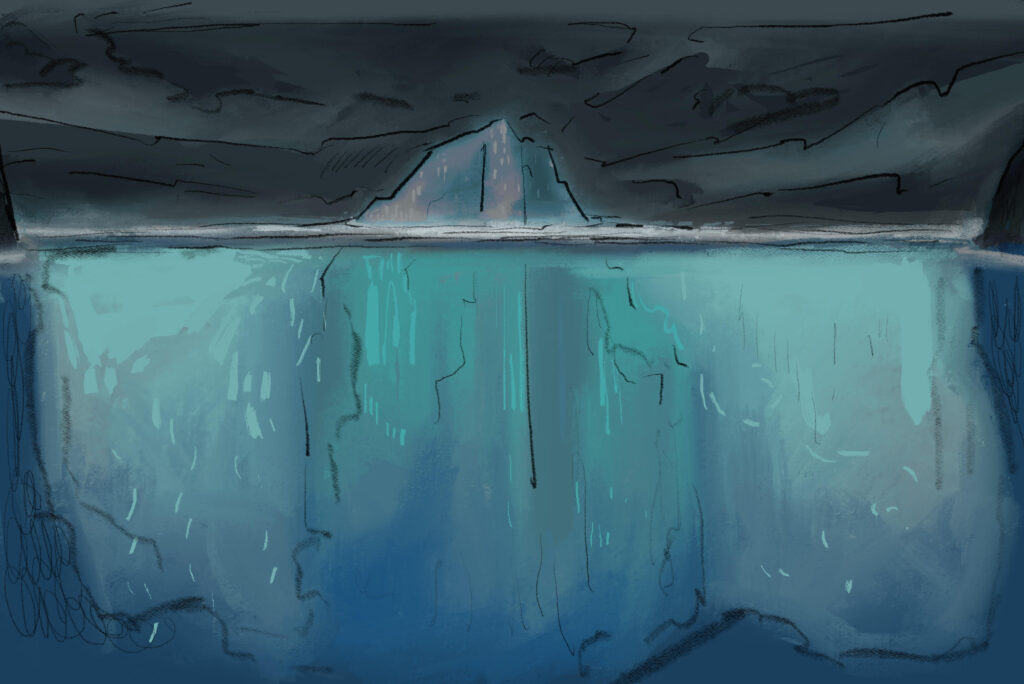

I had little clue that my first conversation with William would bring me here. We had messaged but hadn’t spoken face to face in almost a decade. But that closeness we had as kids when you call someone a brother, doesn’t just go away. When we saw each other for the first time in eight years, the conversation flowed just as easily. I knew we were still the best of friends. Despite our friendship, or partially because of it, William has embraced his new identity as an atheist.

While he would try for twenty years to personalize his faith, desiring to stay in the LDS despite his parents’ departure and his wife’s decision to remain, adapting the church doctrines to fit his needs simply wasn’t enough. His only recourse was walking away.

Fifteen Years of Friendship

As a Mormon, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), six-year-old William Smith had a duty to maintain his faith in God by feeling the presence of the Holy Ghost. The Holy Ghost would convey the light of God to him, and from that light, he would receive personal revelation. This is the case for all abiding Mormons. But Smith’s conviction in his faith, referred to as ‘testimony’ in the LDS, was not weak from a young age, it was non-existent. In a bid to repair his faith, his church leaders instructed him to question these doubts, but those questions only spawned more answers that led Smith down a path away from the LDS. At age eighteen, usually between finishing secondary school and getting married, members of the LDS who plan to remain members of the church, are expected to go on a mission and spread the church’s teachings. His current wife, Catherine, went to the Philippines and Smith’s brother, Andrew, flew to Guatemala.

Meanwhile, Smith was assigned to suburban Ohio. “Wasted time,” he says, comparing himself to those friends who finished their undergraduate degrees and were moving further ahead in their professions. “This is your fault,” he says, jokingly levelling blame at me, an avowed atheist.“I was fascinated by you. I didn’t think people like you existed. That they could exist.”

My background was what made me so fascinating to Smith. I didn’t think it was as worthy of interest as he did. I was born to a lapsed Catholic and a Muslim who’s been in a mosque twice. My father attended St. Michael’s College School from Grades 9 to 13, attended mass every Sunday and occasionally on Wednesday, and then stopped the day he turned 18. My mother was born in Syria to a typical Sunni family, one that attended Mosque only if their cosmopolitan party schedule allowed—which it rarely did. Where Smith and I grew up in the United Arab Emirates, multi-ethnic heritage was fairly common. “You were someone that was fulfilled without religion,” he says. “That was fascinating to me.”

The 2021 Canadian Census found, for the first time, that a plurality of Canadians, 34 per cent, identify as ‘atheist’ and ‘not religious.’ Taking the top spot reserved for Catholicism since confederation, religion’s decline in Canada is of little surprise to Smith. For over twenty years Smith would try again and again to feel true faith while following the teachings of Joseph Smith, the LDS’s founder. Finding that doing so also meant agreeing with the many outdated doctrines and covenants of the church, however, it became inevitable that Smith would depart the church altogether.

Smith calls himself an atheist now, a term that would have filled him with dread as a boy. He was raised to believe it was impossible to have a happy and whole life without the LDS Church’s form of Americanized Christianity. His struggles as a former member of the LDS encapsulate the feelings of Canadians toward religion and the country’s overall decline in religiosity. While Smith’s experiences don’t reflect those of every non-religious Canadian, his issue with outdated teachings may relate to other formerly religious atheists. The LDS Church’s inability to confront its past and practices, including rampant racism, misogyny, and textbook queerphobia, contributed to Smith’s departure. He says, “Returning for me now, is impossible.”

Census 2021

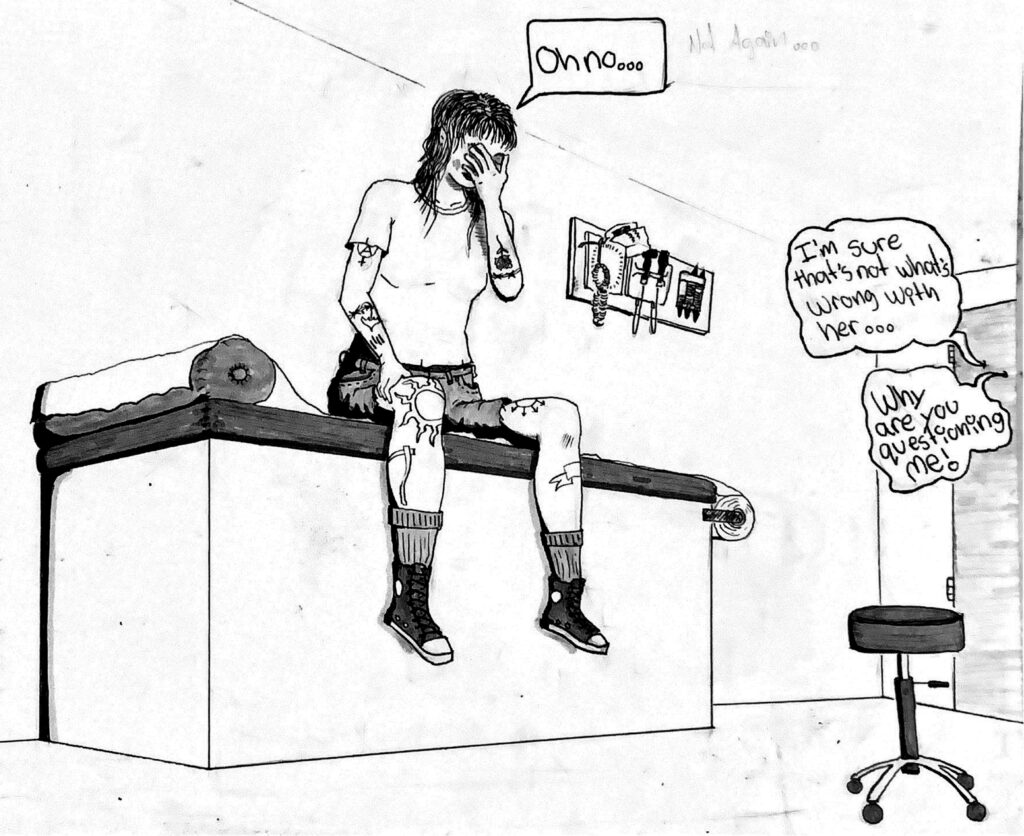

When I visited a Mormon church in Toronto, the ideals I heard espoused by members were the same as those that drove out Smith. The building I went to is the largest Mormon church in metropolitan Toronto, its concrete steeple and façade imposing and better suited to the federal triangle in Washington, D.C. Kitty-corner to a Real Canadian Superstore and across the street from the Ontario Science Centre, I expected more than a drab Protestant church. Inside, the carpet was a faded pastel green, every surface and shelf decorated with textured corduroy wallpaper and a horde of blond-haired and blue-eyed Jesuses. After a tour with a pair of missionaries from southern California—Sisters Jones and Langford, who offered unprompted explanations of how dating works and when people of my age group are welcomed at activities—I settled into a back corner pew for the service. Underdressed in khakis with my sleeves rolled up and tattoos exposed, I stuck out in the back as I took notes, splitting my focus between the sermon and, out of curiosity, trying to feel some moment of faith just as Smith had.

I rose to stand out of respect for the hymns as well, later shouldering my coat and camera bag to climb to an upper-level room for Elders quorum. My first thought was that the air conditioner was running far too strong for early March, and my second was one of shock as I was directed to a waiting seat. They were expecting me. With unvarnished words but respectful diction, the leader of the men’s meeting of Mormons, Rob Clendenning, brought his brethren to order. Clendenning—a bishop—is less a preacher in the meeting than he is the meeting’s referee, ever ready with the whiteboard to illustrate a concept, or the TV remote to run a clip of a past LDS leader’s wisdom.

That day, the brethren discussed ‘Ways to Resist the Adversary,’ with Clendenning and a handful of his fellow over-forty men agreeing to speak with me after the Elders quorum ended. When I mentioned the results of the 2021 Canadian Census, Clendenning lamented the decline of religion more generally, not because he did not know that religion was falling off a cliff, but because it reminded him of his son, who was “struggling with his faith.”

“People are finding community elsewhere. It’s a shame,” one man says. I asked them about the LDS’s response to a decline in membership (members are those who pay tithes). “Secularist and Marxist upbringings rob people of real community and friends with common values,” one of the men explains. “But God’s children will always know where the true community can be found.”

The Desert

It was a bright September day, three weeks into the school year. I’d just turned eleven. I was looking forward to spending my morning snack break like how I spent every lull between lessons—reading, eating while reading, and then squeezing in a game of British Bulldogs. Instead, I almost lost my dog-eared copy of Percy Jackson and the Titan’s Curse as my sister, Keats, plunged from the ether to drag me across the playground. “Here! I’m done!” she said, throwing up her arms before sprinting to her friends.

I looked over my shoulder and tilted my head up at a tall blond boy with a nervous smile. I was an awkward, scrawny kid still waiting for a growth spurt, but Smith was like no one I’d ever seen; tall and blond with blue eyes. He looked like something out of a kid’s Abercrombie catalogue. And he wanted to hang out with me? “Keats said you’re twins?” I nodded, hesitating to take his outstretched hand. What kind of kid shakes hands? “You’re Canadian, too?”

My eyes went wide. “I’m from Burlington!”

“I’m from Raymond!”

“Where’s that?”

“Calgary. Well, near Calgary.” Smith looked over my head. Some of our classmates were playing rugby on the ‘playground’—a sheet of asphalt the size of a soccer field ringed in by sun-bleached porta cabins. I looked on warily, having bloodied my knees enough for one lifetime on that grey and black turf. “Do you play?”

I shook my head. “I play hockey,” I said. No one in my class played. Smith shook his head. It was then that I wondered what kind of freak my twin had left me with. What kind of Canadian didn’t play hockey? “I play video games.”

“Halo?” I asked and he grinned. We were friends. Inseparable, my parents say.

Smith learned about my religious background over the following days and weeks. But, our closeness did not stem from religion or our shared nationality. He was just easy to talk to. “There was always a disconnect between you and other boys your age,” my mother says. “Everyone played soccer; you didn’t. Everyone played rugby, but you didn’t. Those things mattered to you before Will. For the first time I could remember, you came home and you were excited.”

It was an odd thing, speaking with my mother about my friendship with Smith. I remember interactions where my parents warned me about him and that he would try to convert me. My parents were joking, I later learned. But I was certain there was a core of true worry in them. I would learn from Smith that he was asking me so many questions for a reason. As a child, he hoped to learn about what was possible and what might work for him, so he could make his faith his own—deconstruct it and, in the process, personalize his relationship with God and the divine.

Yet the LDS Church and faith were not trained to aid his personalization. Far from it, as Smith sought ways to permit himself to explore his faith in greater depth. “I knew that in other religions, like in Christianity, someone could go to an ecclesiastical leader of some kind if they had doubts, but I didn’t know people had those doubts,” Smith says. “Now it’s easy, but then, I couldn’t wrap my mind around how someone could be happy and not Mormon. Or happy and not religious at all.”

O Father, Where Art Thou?

When I spoke to my father, it became clear that the level of faith personalization Smith hoped for was common, and sometimes encouraged, by the Catholic church. When I asked him questions about his religion growing up, my father said, “I was raised Catholic?” You wouldn’t know it to look at him, that this tattoo-covered lefty journalist was once, as he says, a practicing Catholic. Church twice a week, a sermon every morning at school and a pro-life pin on his lapel. It was because of my dad that times would emerge when I believed that Smith and I should hang out less.

When my dad left Catholicism, it wasn’t in some blaze of glory. He just stopped going to church, sitting in respectful silence while his parents blessed their meals. “I started looking at everything with a critical eye,” he says, explaining that he would go to church more on his own, as well as places beyond his usual experience.

It was at that same time in Smith’s life when he should have been expanding his friend group and growing as an individual that existing LDS doctrines drove him back into the faith, making his continued membership implicitly contingent on his doing a mission. Not doing so would isolate Smith from family and friends, and keep him from the fledgling romances that define young adulthood for many LDS members. “I was told by Nolan to focus on other things for a while,” Smith says, speaking of his mission leader in Ohio, Nolan Danes, “to let things sit and to not do anything.” In choosing to stay, though, Smith could remain a part of the only community that had always been a constant in his life, lying to himself until he believed.

Learning about my dad’s experience encouraged Smith to ask more questions to the church’s leaders. In the summer of 2015, aged eighteen and expected to leave for his mission, Smith had yet to decide if he was going to go at all. As he had when he was young, he thought going to his father, would provide the answers.“He asked me what I wanted,” Smith says. “He knew I hadn’t decided, but he was curt. He rarely spoke like that around us, and never to us.”

Smith’s father told him to just figure it out because he was running out of time. “Unbeknownst to me, he was experiencing some of the very same doubts,” says Smith of his father. “He felt pressured to give me the answers the institution wanted him to give me, but as a father he wanted to give me the answers he was passionate about.”

Smith chose to go on his mission. When he was all set to leave for Ohio, just as I was starting my degree at York University, we started talking again over Facebook Messenger. He convinced me that he was stronger than ever in his faith. “I believe in the teachings of my church, and my faith in God and Jesus are solid. But many of our ‘beliefs’ are heavily influenced by tradition and a misinterpretation of ‘truth’ which has become accepted as doctrine. Yes, we believe in modern revelation from God and also through a prophet and apostles, but they’re still just as human as any Joe Schmo on the planet and they make mistakes.”

Hearing this, to be frank, blew my mind. Smith was doing what almost every one of our religious friends always said they would do but either overcorrected or failed to do—he was personalizing his faith. Hearing this at the time shocked and surprised me, but I was so proud of him. But, all along, Smith felt nothing. “I was lying to myself and others,” he says. “I can recall times where it’s possible I felt the Holy Ghost, but I seriously doubt that those experiences were genuine.”

Deconversion

After he finished his mission, Smith decided it best that he should try recommitting to his faith. About to get married and advancing within the LDS, Smith decided it did not matter if he believed or not. Faith would come as he became a priest, using his story to guide other members while pushing back on some of the Church’s conduct that unfairly isolated marginalized groups. First, he would have children and become his household’s priesthood holder—ordained to lead the religion and perform religious rites within his immediate family. By age thirty, he might be a bishop like his father and his father before him, and by forty a Stake President—the highest authority for 5,000 card-carrying Mormons. From there, it would be a few years as a mission leader, sending his children on missions and seeing them married with children before twenty like him. And from there, the sky’s the limit.

In the LDS Church, the people with Smith’s liberal, progressive beliefs who remain members have created a kind of trickle-down effect. In Smith’s view, these changes have not been coming fast enough, and by signing onto a life of the priesthood, he would be agreeing with everything the church had ever done—which, to Smith, meant every act of violence and persecution against Indigenous or queer people, and existing LDS doctrines that perpetuate misogyny, queerphobia, and racism.

With that revelation, Smith had to step away, frank in his explanation of his feelings. “I was deeply uncomfortable with several of the LDS Church’s policies and practices, so it is a relief to step away and have opinions and values that are entirely my own and not a reflection of a much larger institution.”

Blame

Growing up, I was often angry with Smith. His religion kept him from childhood activities, like sleeping over if my sister had friends over. But, in Grade 9, Smith told me about a crush he had on a girl. He’d confessed it to his dad, who expressed disappointment. It broke Smith and after seeing him exposed and vulnerable, I consoled him. He was honest, and in hindsight, I respected that. In 2018, it was my turn to return the favour and be honest with him.

At the time, I needed Smith’s help with a genealogy project—the LDS Church runs one of the leading genealogy and family history databases—and as we talked it started feeling wrong that I hadn’t told him I was bisexual. He had shared so much with me about his religion, life, and his struggles with his parents’ separation, and the move away from his friends in the UAE. He had bared so much of himself, and I wanted to return that vulnerability. I knew doing so would give him all the power over the future of our friendship, but his reaction eased all my anxieties and showed me exactly the kind of man he was becoming. “I think you’re one of the greatest friends I’ve ever had,” he said in our Facebook Messenger chat in response to my coming out. “I’m assuming you were resistant because of my religious views? My parents raised me far differently than many other members of my faith, and I’m glad for it.” And all that love and acceptance, he went on to explain, came from the LDS.

The reclamation of love from religion is a common one, but with Smith there was always a barrier between us built by his fear and, without me realizing it, my upbringing and opinions on religion. Yet he accepted me, all while I looked down on him for believing and trying to have faith for twenty years.

New Faith

In the winter of 2021, before he chose to identify as an atheist, Smith tried for the last time to connect with his faith. He entered the Edmonton Temple with his wife, finding his seat and taking the sacrament tray. Holding small cups of water and cubes of white bread, he passed the tray to Catherine without taking it himself. In doing so, he declared to himself that he was no longer a Mormon.

A new sense of peace overtook Smith during the sermon. He later said goodbye to his wife as she went to bear her testimony in the Women’s Relief Society, the women-only meeting for members of the LDS Church, and dropped off their two-year-old son at daycare. Smith gave Elders quorum a wide berth before escaping to the solitude of his car’s passenger seat. Looking up at the church, he felt that he had lost so much time, in his view, to outdated doctrines. “I would spend so much time reading the scriptures that I would have a spiritual experience,” he says. “But I don’t believe any of them came from God.”

As much as Smith was afraid growing up, he is certain of himself now, his faith broken down in favour of new faith in himself. Though at times he considers trying again, knowing that to question is good enough, the experience of departing the LDS church was the best thing for him. He says, “There’s no pressure to be people we don’t want to be anymore. We can talk about things and share opinions and thoughts that aren’t clouded by what we think the church wants us to believe.”

“I have realized I don’t have faith in God,” Smith says, his actions proving as much. Beyond his process of deconversion, he still feels connected to the LDS Church through his family. He doesn’t blame his church leaders for his lack of faith, nor does he place the bigotry of the LDS Church at the feet of regular members. However, Smith does believe that most Mormons won’t go through the motions of religious ritual, as he did. After all, to Smith, they are still supporting an institution that perpetuates systemic racism and queerphobia. “I really hoped the leaders of the LDS Church would change their policies surrounding queer people,” he says. “This has not happened, nor do I think it ever will.

“But I have changed. I have become my own person.”