BY LIDIA RAJCAN

ART BY S35

———————————————————–

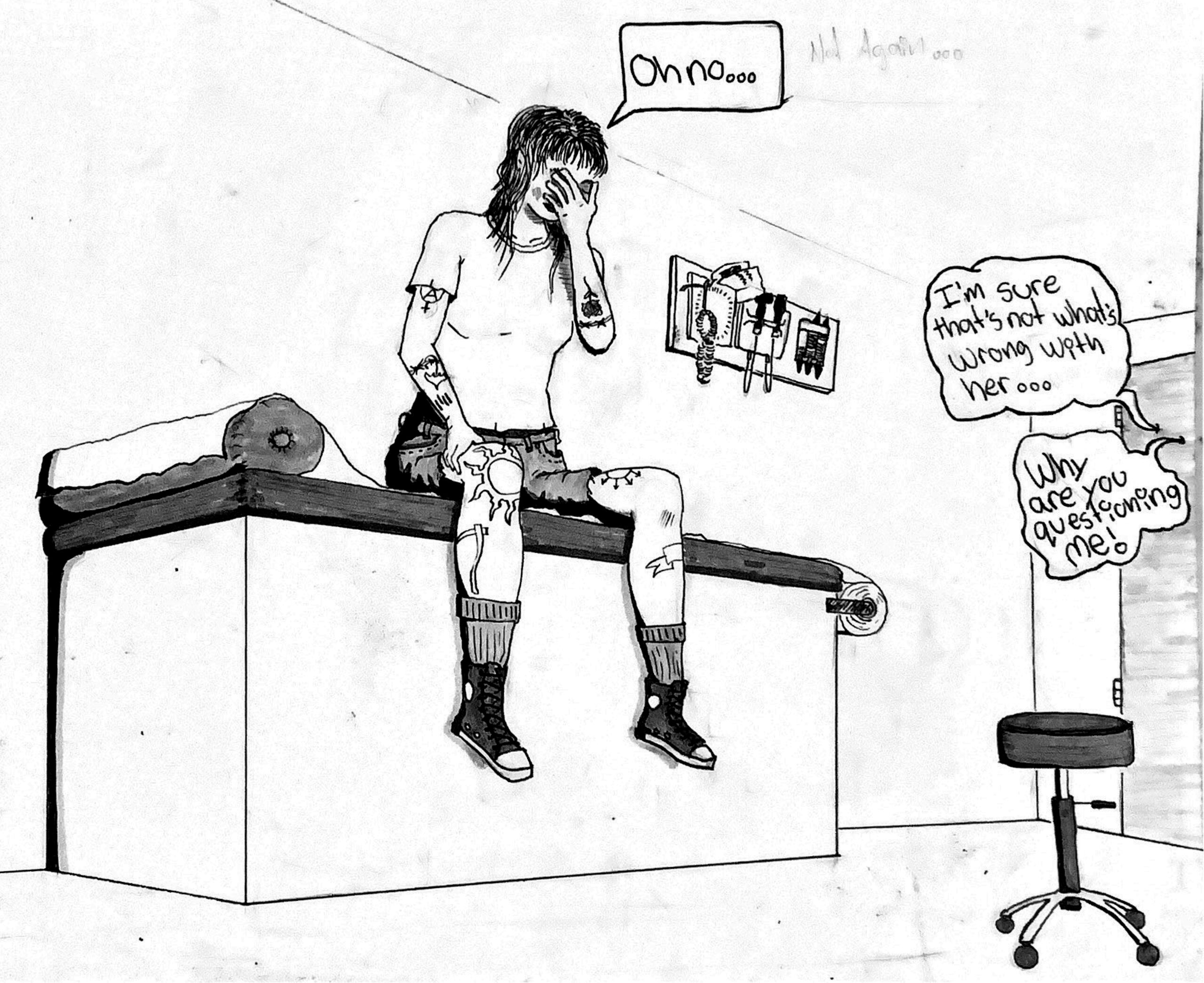

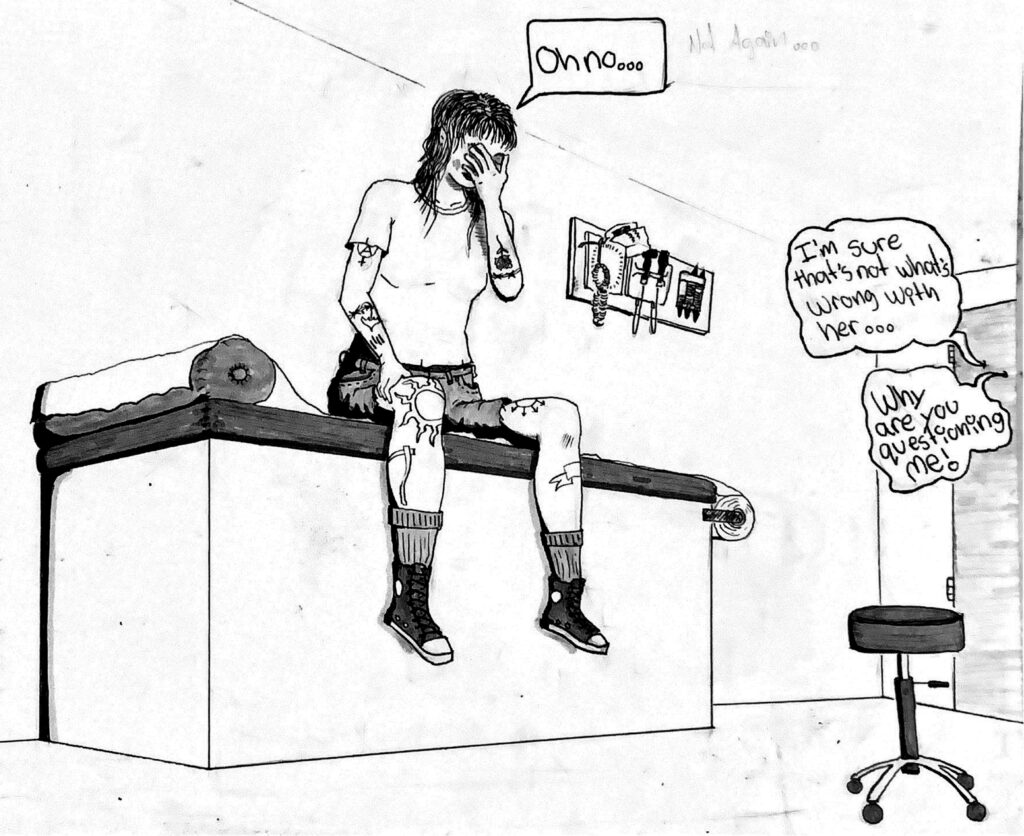

The doors of Guelph General Hospital slid open as Taylor Taylor made her way into the emergency waiting room with her husband, Paul Taylor, just behind her. It was 2011 and the two were in their early twenties. They had concerned, frantic looks on their faces. Taylor was in pain. Her lower abdomen was throbbing, she was uncontrollably vomiting, and she had no idea why. Even the feeling of her baggy sweatpants and sweatshirt against her body hurt. Her menstrual cycle was just about to begin, but the pain had never pierced and burned as much as it did that day. Taylor and Paul waited five hours before being ushered into an available room. The couple’s one-year-old son was at home with Taylor’s in-laws. Sitting down in the two available chairs on the far side of the hospital room, they looked over to the doctor who stayed right by the door. “He didn’t move from where he was standing,” Taylor recalls. His arms were crossed, and his body language was rigid. “I tried not to overthink that,” says Taylor. “But then he asked me a couple questions, cut me off a few times while I was explaining how I felt, and then left the room.”

“He didn’t do an exam,” Taylor continues, “didn’t put his hands on me, didn’t push on my stomach, didn’t do an internal exam, didn’t order an ultrasound.”

Upon returning to the room, the doctor entered with a nurse who looked visibly distressed. Her cheeks were stained with tears, which Taylor, looking back, assumes must have come from disagreeing with the doctor’s medical decision. The doctor, still rigid and cold, crossed his arms and said, “You probably have gonorrhea.” Stunned, Taylor waited for some kind of clarification. “You probably have gonorrhea,” the doctor repeated.

“I’ve been with my husband now for three years. I’ve not been with anyone else while I’ve been with him and I have had very few partners before him,” Taylor says. She went on to explain that she had been tested consistently between every partner and that her last viral testing was clean. “Well, I don’t know you and you don’t know me, so for all we know, you could be lying,” said the doctor. At that moment, she froze. Humiliated, confused, and lost. No words came to mind, no matter how hard she tried. She couldn’t believe what she was hearing. Tears streamed down Taylor’s face as the nurse stepped forward and administered an antibiotic shot meant for gonorrhea. With her heart racing, face burning, and tears still falling, Taylor left the hospital.

“It felt like the least dignified form of healthcare I’ve ever received,” Taylor recalls. “It just felt like he went, ‘Oh well here’s some tattooed-covered young girl in here with her boyfriend and she has pelvic pain so it’s an STD,’” Taylor says about the interaction. The emotional toll of this hospital experience has stuck with Taylor for a long time. It’s followed her to, unfortunately, many other appointments she’s had; to every specialist, doctor, or practitioner interaction since.

Taylor currently works as a scrub nurse in the OR, so when she looks back at her early experiences dealing with hospital visits and doctors as a patient, she understands that world a bit better. And research supports Taylor’s anecdotes. Gender bias in health care is widespread and can happen at any stage in one’s medical process. This bias inevitably has an impact on patient care and diagnoses. When a woman enters a doctor’s office, her symptoms are less likely to be believed or taken seriously. There are also significant gaps in medical research pertaining to women, which leads practitioners to have a lesser understanding of how symptoms of various medical conditions present in women.

“She wanted to learn how to maneuver within the healthcare system…She never wanted to feel so helpless again..”

The healthcare system is ill-prepared to address women’s health. This enables the misdiagnosis and mistreatment of many women seeking help. Also, women’s healthcare doesn’t have the same scientific backing that men’s healthcare does. A 2018 Hindawi literature review on gender bias in health care revealed that doctors often view men with chronic pain as ‘stoic’ or ‘brave,’ while viewing women with chronic pain as ‘emotional’ or ‘hysterical.’ Duke Health, a health research centre out of Duke University, reported that “one in five women say they have felt that a health care provider has ignored or dismissed their symptoms,” suggesting that “women’s perceptions of gender bias are correct.” A historical belief in men making the best subjects for medical research drastically slowed women’s healthcare by leaving doctors with a limited understanding of the health of female and intersex people. Substantial consequences often take the shape of delayed diagnoses, inadequate symptom management, avoidance of medical care altogether, and medical actions that increase the risk of abuse. In the worst cases, women die.

The Trouble With Bias

By the next day, Taylor was not feeling any better. The shot had not helped and the pain stayed as severe as it had been initially. Taylor came back to ER. Her symptoms had grown worse to the point that she struggled to walk. A different ER doctor sent Taylor straight to emergency surgery due to an ovarian cyst. The cyst was bigger than a grapefruit and had taken over Taylor’s entire pelvis, something that the previous doctor had missed entirely. “It was actually so large, that had he pressed on my abdomen—he didn’t even need to do an internal exam,” Taylor says. “You could actually feel the cyst on the outside of the abdomen.” Following the surgery, she felt instant relief. Eventually, though, she just felt angry. Angry that the cause of her pain had not been found the first time, and of the humiliation she felt forced to endure. This interaction in the ER sparked an idea for Taylor: I’m never allowing this to happen to myself again. She had felt incapacitated by her ER experience. She wanted to learn how to maneuver within the healthcare system. She wanted to know how to communicate with doctors and voice her symptoms. She never wanted to feel so helpless again. Taylor researched and investigated her medical symptoms. She discovered that plenty of other women had experienced similar issues dealing with the healthcare system. Their symptoms or pain, when it came to reproductive health, had been either misunderstood or ignored entirely.

Holly McKenzie, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Saskatchewan whose research includes reproductive and sexual justice, says, “We need to push for comprehensive sexual health education, not only within schools but also by providing our medical experts with the information necessary to approach their clients in a way that’s patient-centred and safe.” Giving upcoming generations of doctors the support needed to better understand women’s health is necessary, says McKenzie.

A comprehensive research article published by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) highlights the need for more research into reproductive health and disease. According to the NLM’s analysis of PubMed publications, “The number of research articles published on non-reproductive organs is 4.5 times higher than the number published on reproductive organs.” And, when it comes to the two most researched reproductive organs (breast and prostate), the focus is mostly on non-reproductive diseases such as cancer. As for funding and grants, NLM’s analysis of databases from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the National Institutes of Health in the United States shows that grants for non-reproductive organ research are six to seven times higher than for reproductive organs. For NLM, such a long-standing lack of research into reproductive health and disease means that “the acute and chronic healthcare burden caused by reproductive pathologies is likely to continue increasing.” This gap in research has a disproportionate impact on those with uteruses, given that twenty per cent of pregnancies, for example, require medical attention. Political and social pressures play a significant role in perpetuating stigma and slowing down the process of achieving better reproductive health care. “Menstruation is one function that has faced stigmatization that persists today,” the article by NLM notes. Women often feel too embarrassed to talk about this natural process or to even complete essential tasks such as purchasing menstrual products at local stores. Under-researched female experience bleeds through Taylor’s story. Our healthcare system lets women down and leaves them at risk. According to an article that appeared in Time, “Women are more likely to be offered minor tranquillizers and antidepressants than analgesic pain medication.” They are less likely to be referred for further diagnostic investigations than men are, and women’s pain is much more likely to be understood as having an emotional or psychological cause as opposed to a bodily or biological one.

“Unfortunate Women”

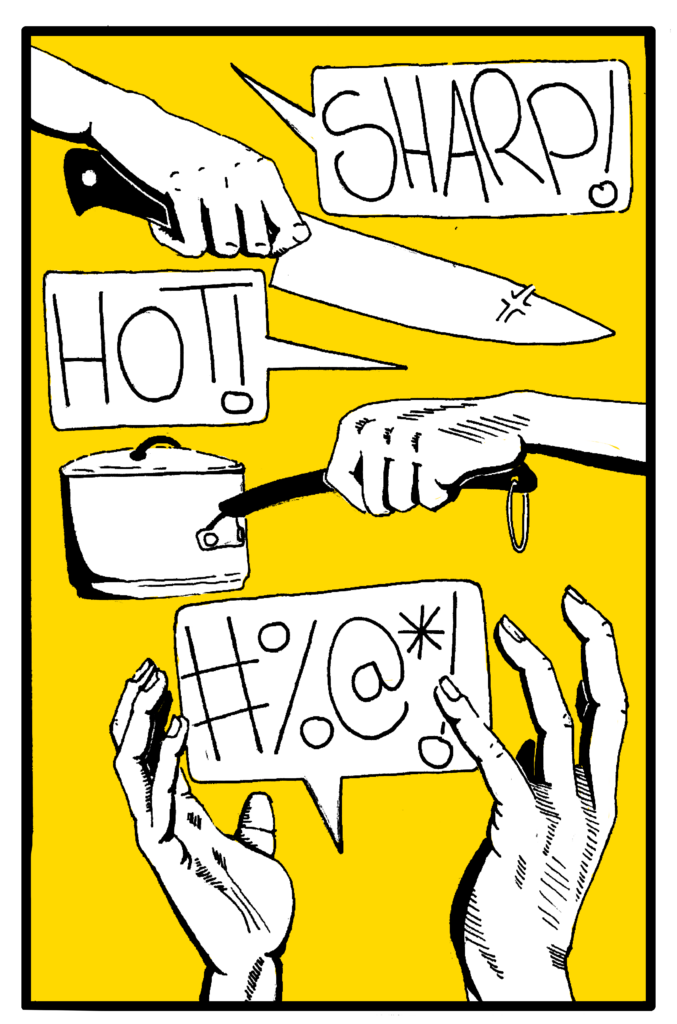

Taylor’s reproductive health issues began years earlier, during her first period. As a young teen living in Guelph, she spent two weeks out of every month at home; the pain from her menstrual cycle was unbearable. She had severe cramping, heavy bleeding, and blood clots. Taylor went to her family physician for help only to be recommended a generic form of the birth control pill. “You’re just one of those unfortunate women who has really bad periods,” Taylor recalls her physician saying. “It planted a seed in me very quickly that there wasn’t any help,” she says. “This was what it was and don’t complain about it because it’s normal.”

Taylor used the birth control pill for most of her teen years, but she developed persistent migraines from sustained use. So, Taylor’s family physician put her on a contraceptive injection known as Depo-Provera instead. The negative effects were immediate as Taylor’s moods changed significantly, feeling constantly angry and depressed. She was struggling so much to the point that her husband, Paul, pushed her to seek help from a professional. Taylor went back to her family physician and was told, blankly, “That’s how women are when on birth control.” Her developing distrust of the healthcare system only grew. Neither her pain nor her birth control experience was recognized no matter what she did or how many times she asked for help.

Jessica Rollings-Scattergood, a gynecologist based in Fergus, Ontario, says she hopes for scientific findings to evolve non-hormonal birth control methods (where hormones are not altered through birth control). “There is a huge skepticism around hormonal birth control,” says Rollings-Scattergood. Evolving this and educating patients on their myriad of options would go a long way to improving patient care. McKenzie similarly notes the importance of early education about birth control and the reproductive system. Women need to know and understand how their bodies will develop, what they may need in these circumstances, and what is abnormal. An article published in The Guardian about women’s healthcare included a quote from a public health researcher at Monash University in Australia, who said, “Essentially, we’ve ended up with a healthcare system, among other things in society, that has been made by men for men.” Due to the lack of research and awareness around women’s health, doctors may fill knowledge gaps with “hysteria narratives,” where emotional instability is usually to blame for pain.

Endless Pain

After her ovarian cyst removal in 2011, Taylor started getting recurrent endometriomas, which are cystic lesions typically found on the ovaries; they indicate a severe stage of endometriosis, never go away, and need to be surgically removed. “I was having surgery every three to four months,” she says. “It was usually the same pattern—I’d wind up in the ER, the situation would be reviewed and I would end up being scheduled for surgery a couple days later.”

“Taylor’s quality of life during this time, which consisted mostly of surgeries and pain, worsened.”

Reading up on her constant endometriomas led Taylor to believe that endometriosis was the source of all her pain. Endometriosis is a disease where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside of the uterus. It can cause severe pain in the pelvis and might start at a person’s first menstrual period, lasting until menopause. The constant surgeries gave Taylor a thorough understanding of the OB-GYN and gynecological staff available in Guelph. And after settling on a gynecologist she felt comfortable with, Taylor began what would turn out to be a six-year process to receiving an endometriosis diagnosis. This diagnosis would allow her to get more accurate treatment and, ultimately, excision surgery. Her gynecologist “was not everybody’s cup of tea,” she saya. “He was not the most liked physician in the world, but what drew me to him was he seemed thorough.” The doctor was short and abrupt. He was not overly welcoming or warm in any sense, but he made sure to listen. For Taylor, it felt like he heard her and pondered everything she said before suggesting a change or new treatment. He stayed informed and her symptoms were never dismissed or viewed as unimportant, which helped Taylor better understand her body. She felt like even without a diagnosis, someone was hearing her and telling her that the things she felt were real. Her pain was not made-up or irrational.

Even if they never got to the bottom of her struggle, Taylor now had someone in the healthcare industry who saw her suffering, her pain, and her trauma, and got to work trying to help. “He ended up removing several ovarian cysts for me over the next little bit while I was trying to figure out the endometriosis portion,” says Taylor. When she asked her family doctor to be referred to an endometriosis specialist, he said, “Well, I don’t see any basis for that.” Taylor had brought with her a sheet of paper outlining endometriosis symptoms—a pain journal—and a symptom tracker of all the things she had been experiencing over the last couple of months including her abdominal pain, excessive bleeding between and during periods, and body pain beyond her pelvis. “It feels futile,” she says. “You’re in pain and you’re frustrated.” Even after doing the legwork of picking a specialist and bringing documentation, her family doctor still pushed back against referring her to an endometriosis specialist.

It took a long conversation, but Taylor eventually got her referral. It felt freeing. While waiting to hear back from the specialist, Taylor had a cyst that needed to be removed. The gynecologist Taylor usually worked with was unavailable. She ended up going with a different surgeon to remove it. The specialist Taylor was supposed to see also asked the surgeon to take a biopsy of tissue. This was the only way to prove she had endometriosis and receive treatment.

Taylor’s quality of life during this time, which consisted mostly of surgeries and pain, worsened. She became so physically ill that it hurt to hold or even touch her young son. Merely sitting him on her lap made her skin feel like it was burning. “I don’t feel feminine, I don’t feel beautiful, I don’t feel smart, I don’t feel healthy,” says Taylor. “It drains everything from you.”

Taylor got her surgery but was frustrated when she didn’t hear back. She called the specialist’s office and asked how much longer it would take. They said, “‘Oh, your referral’s on hold—we didn’t receive a biopsy.’” Taylor dropped to the floor, phone still in hand, she felt her heart racing and let out a few spurted gasps for air, and just cried. They never took the biopsy. “The physician who did the surgery for the ovarian cyst forgot,” says Taylor. This put her referral off for another year, allowing the disease more time to grow.

Heather Thomas, a surgeon at Groves Memorial Hospital in Fergus, says that knowing who you are talking to is important for marginalized groups, especially women. Any first-time interaction with a new doctor allows for a lot of relevant information, like your medical history of reproductive health issues, for instance, to fall through the cracks unless you come prepared to spell it out for the practitioner you’re given. “You might not feel comfortable disclosing personal information because you don’t know them,” Thomas says. Or, you might not know what to disclose. This, she says, is why increasing education around healthcare is so pertinent.

The kind of detail that a patient needs to reveal to a walk-in clinic doctor is much more extensive, and not everyone knows this. In these situations, marginalized groups suffer the most. Their symptoms are disregarded and ignored. Communication is minimal, and finding a solution moves farther out of reach than it should.

After interacting with the healthcare system for some time, people like Taylor start to realize how little they may know about their own reproductive health. Learning about the side effects of birth control after years of being on it is too late to receive adequate care. And learning about diseases that impact women of reproductive age when they are experiencing them comes too late. Understanding how to manage these symptoms, and understanding what happens to the female body at every age, is crucial. If we don’t educate early, we risk late diagnoses and missed opportunities to improve the long-term health of women. We risk exacerbating the stress that comes with being a patient in the healthcare system.

“Though she was scared about what this could mean for her health and future, seeing her doctor in tears helped her realize that he cared deeply and wanted to help her get better.”

Surgeries, medication, new prescriptions, jumping from physician to physician, and potentially never knowing the cause of one’s pain are all issues that plague women struggling with their health. When we fail to fund reproductive health research and educate women on their health experiences, we inflict pain. Taylor was unable to be the mother she wanted to be because of her pain. She was unable to be the partner she wanted to be. She was unable to enjoy the simple things in life for the better part of ten years. All she wanted was for somebody to listen to her. Endless pain should not be her reason for being as strong as she is today.

The Excision

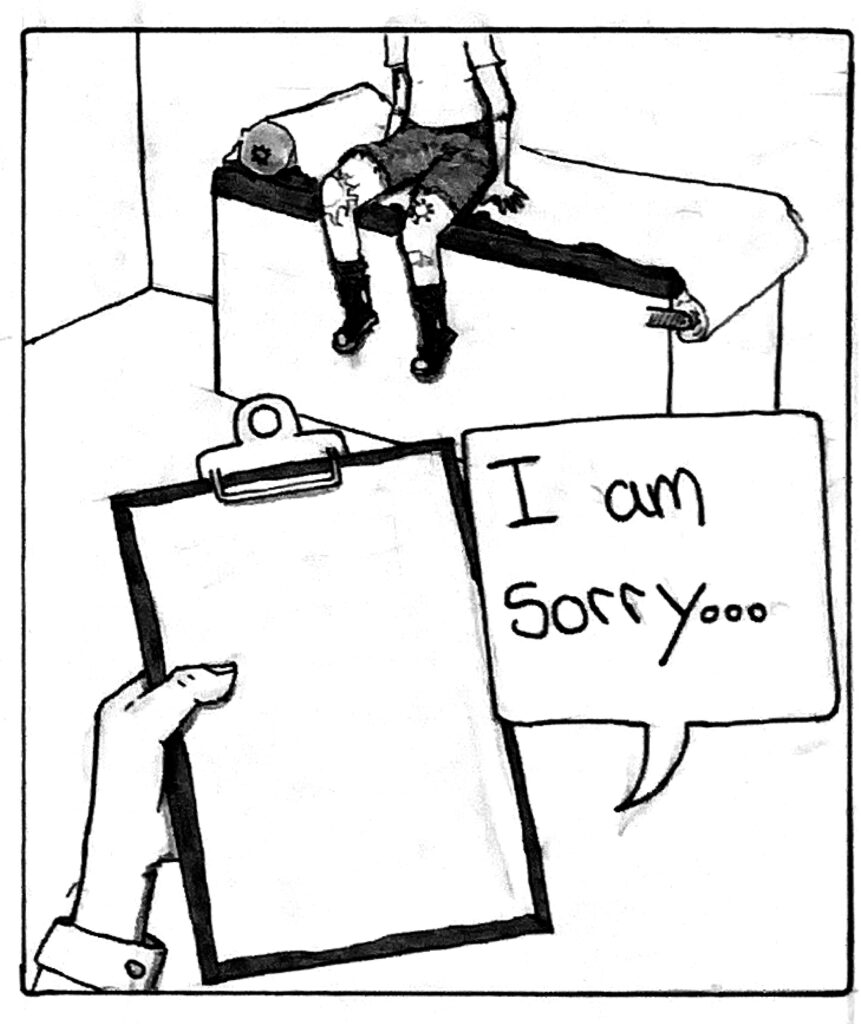

During the stress of not receiving a biopsy Taylor was also a student in nursing college. She was in the midst of exam season when, during one of her exams, Taylor’s professor pulled her out of the classroom. The teacher said, “You look really unwell. What’s going on?” Taylor responded, “I’m in a lot of pain. Something’s going on and I don’t know what it is.” The teacher took Taylor’s vitals. “My blood pressure was super high,” she says. “My heart rate was through the roof.” After denying Taylor’s suggestion to drive herself over to the hospital, the teaching staff called Taylor’s husband instead. “I was diagnosed with ovarian torsion. There was a giant cyst on my ovary that had actually twisted my ovary.” She was rushed into emergency surgery. She was twenty-two at the time, with a son who was now three years old. After the surgery, Taylor’s gynecologist walked into the room. “He had come in to tell me that he had removed my ovary,” Taylor says. “He started crying.” Since he had never really been the warmest, Taylor knew this time was especially serious. She was now short one ovary at a young age. Though she was scared about what this could mean for her health and future, seeing her doctor in tears helped her realize that he cared deeply and wanted to help her get better. If anything, it revealed to Taylor that she had been right to trust him with her health. He said, “I’m so sorry that this is happening to you.”

“That was the first time I really felt like there was actually something wrong, she says, “and what I was experiencing wasn’t normal.”

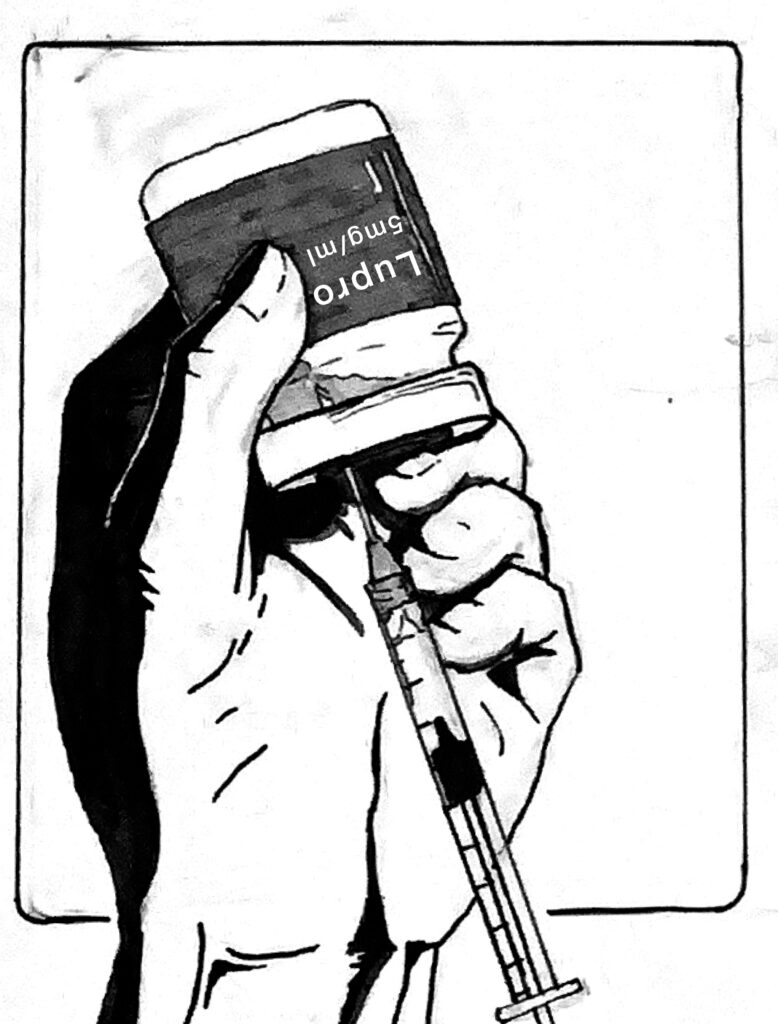

Two weeks later, Taylor got the call from McMaster Hospital. She was going to be seen by a specialist there. In the meantime, she was placed on Lupron. A brand of leuprolide, Lupron is a highly invasive prescription injection used for managing endometriosis-related pain. It forces the patient into chemical menopause by suppressing all of their hormones. Taylor was on Lupron for six years. “That medication gave me my life back.” She had to go off of the medication eventually since her estrogen had been suppressed for so long that she began to develop osteopenia, which caused her to have low bone density. With no other options available, Taylor was put on the waitlist for excision surgery. She was told that the wait could be around two years and it was. Taylor got a cancellation spot. She dropped everything and secured some time off of work, but she had the lingering fear that this might not make her pain go away. “It is a full psychological warfare,” Taylor says. “Like, ‘Am I just mentally ill at this point? Do I have some need to be fixed? Is something wrong with me?’ You start believing that.”

Taylor’s medical team debriefed her after the surgery. The spread of the disease was extensive; she had endometriosis on her left ovary, the whole left side of her pelvis, her posterior cul de sac, and the back part of her uterus. Her bowel had to be excised; she was close to needing a colostomy bag, but luckily did not. The surgery removed both of her fallopian tubes, rendering her effectively infertile. She was almost 30 years old. Her bladder and ureters were completely encased in endometriosis and needed to be stripped entirely and put back into place

Here We Go Again

The goal for Taylor following her excision was to remain symptom-free for five years. However, as she approached the four-year mark, all of her previous pain returned. “I just started the oral form of Lupron, Oralissa, and I am currently waiting for neurosurgery and excision surgery,” Taylor says. The endometriosis is suspected to have spread and wrapped around her sciatic nerve, potentially causing irreparable nerve damage throughout the body.

In recent years, the specialist Taylor used to see retired and a younger surgeon took over his practice. This transfer has been “an absolute nightmare.” For Taylor, the specialist is, in a nutshell, “the reason why people have such a problem with healthcare.” She had to have a cyst removed about a year and a half ago, and when the clinic got the report, he called her in and said, “Why did you have this removed, it was a hemorrhagic cyst. You could have functioned with this.” His suggestion made no sense to Taylor. “That was literally why it was removed,” she replid. “An ER physician said, ‘This needs to come out, you’re bleeding into your abdomen.’” The specialist was unsympathetic. “‘You and I both know she’s not a specialist so we can’t trust her opinion’.”

When Taylor spoke to me last year about her long ordeal, she had ended her working relationship with the replaced specialist. “I am actually, after being with the same clinic for ten years, in the midst of being referred to a new specialist,” she says. “So, we’re in it right now. It’s all back to square one with dealing with the healthcare system again.” In recent months, she’s found a new specialist and is set to have another excision surgery in a year.