Our pets are sicker than ever. Will the pet food industry listen?

BY MATTHEW HANICK

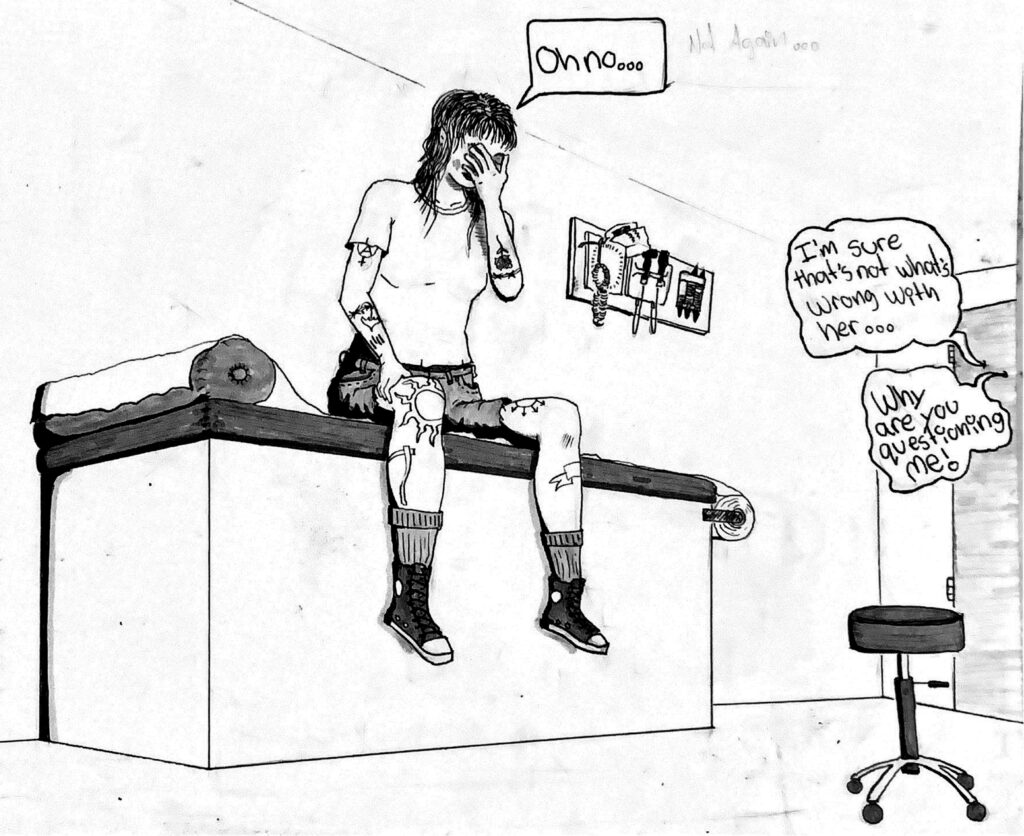

ART BY CALLIE SILVERTON

———————————————————–

Anna Sankar had always wanted a dog. Her heart fluttered as she was greeted by frantic yips and wagging tails at the animal shelter. Among the sea of hopeful faces, one stood out—a nine-year-old husky lab mix whom she named Axel. From that moment on, they were inseparable.

Owning a dog wasn’t easy, but it gave Sankar a newfound sense of purpose. Axel was a voracious ball of life, but soon enough the pair settled into a routine. As a first-time pet parent, raising Axel, whom she considers a son, gave her worries typical of an overprotective mother. Sankar began asking herself questions like: Is Axel eating enough? Is Axel getting enough exercise? Is Axel truly thriving? These fears for her son’s well-being inspired Sankar to learn about canine nutrition.

Initially, Sankar relied on her veterinarian’s advice—but as she did more research, she found herself swaying further from it. She soon became disappointed in the quality of her vet’s preferred brand, which was full of carbohydrates like corn, wheat, and brown rice. “I’ve realized that both for dogs and us, going back to the most natural source is probably the best way to go,” says Sankar. After reading more on the subject, Sankar began feeding Axel grain-free pet food: a high-protein, high-fat, and low-carbohydrate diet that recreated the feeding habits of dogs’ carnivorous ancestors: wolves.

After making the switch, Axel’s health improved immeasurably. He seemed happier and more energetic. Once dull and prone to shedding, his skin and coat now appeared thick and glossy. Sankar noticed subtle differences, too. Axel sneezed less and was far more affectionate. Sankar was confident she had made the right decision.

Then Axel died—suddenly. Sankar had left him alone for one moment, and then he was gone. She says, “It was really unexpected.”

Sankar is one of countless pet owners who have recently decided to take their pets’ health and nutrition into their own hands. Some believe that modern dogs and cats have been pampered for too long and are now paying the price with disastrous health outcomes.

The pet food market is a multi-billion-dollar industry dominated by a few major companies. In recent years, these companies have leveraged their financial power to sponsor leading veterinary medical organizations and conduct research through their own private institutions. While established companies offer a broad range of traditional, grain-inclusive products, new boutique, exotic, and grain-free companies focus on niche diets that mimic natural carnivorous diets, responding to the rise in diseases among cats and dogs. Although it is modelled after cute puppies and darling kitty cats, don’t be fooled: the pet food industry is cutthroat, competitive, and, of course, highly territorial—with implications that making the wrong choice could harm your pet.

Fat Cats and Big Dogs

Fifty-nine per cent of Canadians own a cat or dog. It’s easy to understand why—owning a pet can bring comfort, routine and structure to daily life. A 2016 study found that pets offered individuals emotional support, security, and a sense of purpose in their lives.

Thanks to a steadily rising trend known as “humanization,” the tendency of humans to attribute human-like qualities and behaviours to their pets, people have become increasingly attached to their animal companions, blurring the boundaries between pets and family members. As we develop increasingly personal emotional connections with our dogs, their sudden deterioration comes as an even greater shock. The downside of treating pets like people is that owners forget to care for them as animals.

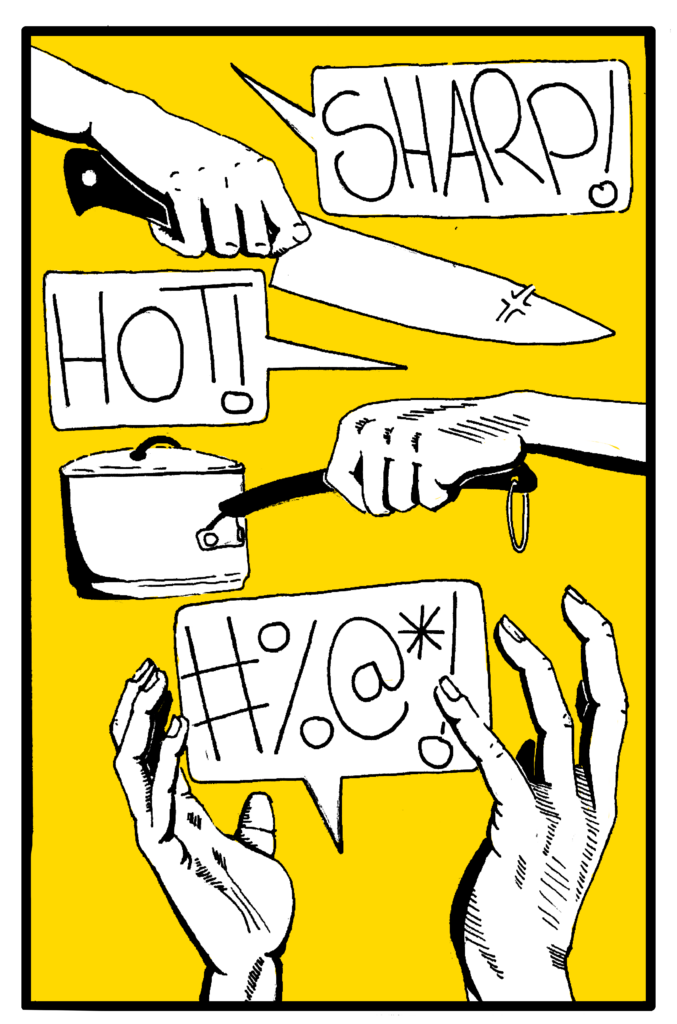

Pet obesity is a silent epidemic in North America, affecting fifty per cent of dogs and sixty percent of cats. According to VCA Animal Hospitals, overweight cats and dogs tend to die some fifteen per cent earlier than their regular-sized companions and are more likely to experience increased rates of diabetes, cancer, arthritis, and other chronic, non-communicable diseases. Animal advocates argue that, like in humans, small animal obesity is made possible by staples of the modern Western diet: carbohydrates, processed foods, and sweets.

“How can it be that all these dogs are obese,” asks Daniel Schulof, CEO of KetoNatural PetFoods and author of Dogs, Dog Food, and Dogma, “when it would seem like the easiest thing in the world to control?” In 2014, he set out to find the answer. An Ironman triathlete and ultra-marathoner, he began researching canine obesity upon learning his dog Kody suffered from it despite receiving athletic levels of exercise. Schulof’s realization took him by surprise—wasn’t he doing everything he could as a pet owner to show his love and care? Schulof soon learned that Kody was among millions of cats and dogs suffering from a preventable disease.

Across the board, carbs are the most common ingredient in pet food, often making up more than half of the product by weight. The most glaring reason why is that these inexpensive ingredients—corn, wheat, barley, oats, and rice—are some of the most fattening on the planet. When pets eat these foods, their insulin levels spike. Insulin, which helps control blood sugar, also signals the body to store fat. Just like in humans, high insulin levels lead to weight gain in dogs.

Not all carb-containing foods cause the same spike in insulin. Different foods impact blood sugar in various ways and are measured by the glycemic index. Cereal grains tend to have some of the highest GI scores, while legumes, peas, and lentils score much lower. However, veterinarians strongly believe that grains are essential for a balanced diet and largely determine what’s recommended for our pets. “Just like in human nutrition, there’s a whole bunch of food cults,” says Kate Shoveller, a professor of animal biosciences at the University of Guelph.

“Just try to imagine the public backlash that would ensue if it were revealed McDonald’s owned the research facilities producing much of the world’s nutritional science and wrote the textbooks being used in medical school.”

– Daniel Schulof

Schulof says vets rely on the ‘calories-in, calories-out’ methodology of weight management, where changes in weight are determined by calories that are consumed as food and burned from exercise . But are the ancestors of gray wolves and African wild cats built for this lifestyle?

“There’s data on the fact that dogs and cats select much higher protein diets than what the average commercial provides them. So, if we went out into the wild, these animals would prefer meat,” says Shoveller. However, veterinarians don’t necessarily think the wild animal diet is the ideal diet for pets. Schulof says that food production companies love carbohydrates more than pets, and they have worked with regulators, researchers, and veterinarians to keep them at the forefront of our pets’ diets.

According to Bloomberg Intelligence’s Pet Economy Report, the global pet food market, which is currently valued at US$350 billion, is projected to grow to US$500 billion by 2030. The top food companies have made a fortune by marketing their products through veterinarians who, in turn, promote them to their clients. If this strategy seems familiar, it’s because it was borrowed from the human-based pharmaceutical industry.

Hill’s Pet Nutrition, a pet food company that produces cat and dog food focusing on specific health needs, was acquired by the multinational consumer products corporation Colgate-Palmolive Co., which still owns it today. Traditionally known for oral care products, the leap into pet food might seem like a departure. However, upon acquiring Hill’s, Colgate experienced success by recreating the same campaign, which involved promoting its dental products directly to consumers through their dentists. Colgate opted to apply a similar strategy to its newly acquired pet food line, highlighting to the public that Hill’s dog food had earned the endorsement of veterinarians.

Hill’s experienced a meteoric rise in sales, soaring from US$40 million in annual revenue in 1982 to nearly US$900 million by 1997. Hill’s had cemented its brand identity by concentrating on marketing initiatives tailored for veterinary professionals. The company broadened its product range by introducing a complete line of “prescription” pet food products, similar to medications. Even though these products are labelled as prescription diets, they do not have FDA approval and have been involved in numerous legal disputes for misrepresentation.

The success Hill’s experienced by building inroads with the veterinary community became the blueprint. Mars Petcare (Royal Canin) and Purina (Pro Plan) recreated this with their brands. Most pet food brands belong to five companies, each as prominent, influential, and consolidated as its human-parent company. The top five include Nestlé-Purina Pet Care, Mars, Inc., Hill’s Pet Nutrition, J. M. Smucker and General Mills. Together, these companies are responsible for more than eighty percent of the pet food market.

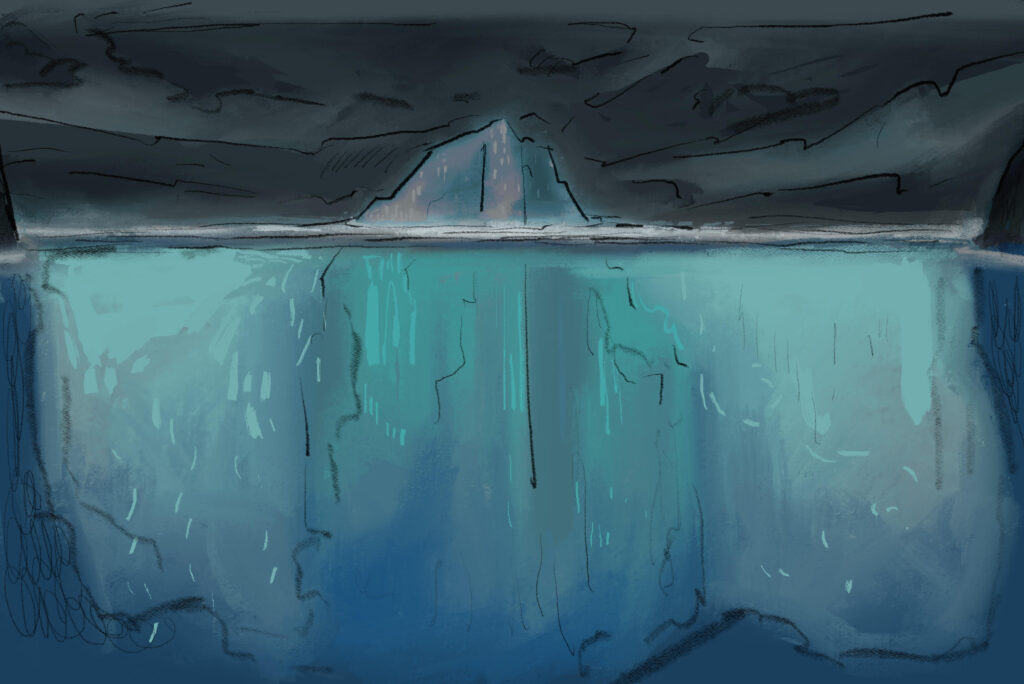

Most of the published research on animal nutrition is conducted at private research institutions owned by pet food companies like Hill’s Pet Nutrition, Nestlé-Purina, and Mars Inc. Many of them have, over just the past few years, used their massive financial influence to sponsor the most influential veterinary medical organizations publicly. For example, in 2017, Mars, Inc., the owner of Royal Canin, bought VCA Animal Hospitals, a network of over 1,000 veterinary hospitals in the United States and Canada.

Schulof says giant food producers normalize the use of ingredients by swaying information on animal nutrition in favour of profit. Mars Inc. owns the results of its research, and it’s up to them to decide what to submit for publication in a peer-reviewed journal and what to keep for itself. Schulof sums it up best in his book: “Just try to imagine the public backlash that would ensue if it were revealed McDonald’s owned the research facilities producing much of the world’s nutritional science and wrote the textbooks being used in medical school.”

Even though cats and dogs can often digest carbohydrates without problems, Schulof says they still cannot do so without gaining weight, nor do they require such high quantities in their diets.

Both wildcats and gray wolves are carnivorous, meaning they only eat meat. The grain-free movement in pet food seeks to replace starchy cereal grains with alternative carbohydrates that resemble the diet of their wild ancestors. Instead, grain-free foods primarily consist of meat, bones, tendons, fruits and vegetables. Schulof says that by removing grains, this diet offers a cleaner and more natural ingredient list that could help address issues like obesity in dogs.

In 2017, grain-free foods experienced robust growth, tripling from six years prior to make up forty-four percent of that market. But then the unexpected happened.

Hour of the Wolf

In July 2018, Valerie Jait walked up and down the aisles of her store, Global Pet Foods, a Canadian pet food and supplies retailer specializing in natural and holistic pet food and treats. Before the store opened, she made sure each display looked right, the floors were clean, and the dogs had fresh water. Jait took pride in her work, arriving early and working a nine-to-five shift alongside her employees. Although she helped manage four locations across the city, she was typically found on the sales floor.

Not only was Jait a knowledgeable salesperson, she genuinely enjoyed talking with pet parents—but not that day. Out of nowhere, the FDA released an update warning of increased rates of heart disease in dogs eating “grain-free” pet food—the same pet food brands that lined Jait’s shelves. Panic ensued on the sales floor as customers stormed in, screaming, demanding answers. The fallout was swift and severe.

A disease included in the report was canine dilated cardiomyopathy, or DCM—a heart disease that makes it harder for the heart to pump blood buildup of fluids in the chest and abdomen. While certain large breed dogs have a genetic predisposition to DCM, the FDA expressed concerns amid reports affecting smaller breeds. Reports that were sporadic between 2014 and 2017 spiked after the agency notified the public about the potential diet issue in July 2018. Between 2018 and 2019, the FDA received 517 reports of DCM, with 222 of these reported between December 1, 2018 and April 30, 2019.

The FDA investigation suggested that while the underlying cause of DCM is unknown, the majority of cats and dogs listed in connection to the disease were eating grain-free diets. Even though it wasn’t until the following year that the FDA released a list naming sixteen brands that were linked to the spike in heart rates, the damage was already done. Shortly after the follow-up report in 2019, Canadian media outlets picked up the story, reiterating the sixteen brands and prompting salacious, condemnatory headlines.

The general impression that grain-free dog food causes DCM remains in the consumers’ minds due to this harmful media campaign that targeted everyday pet owners. “It scared me a little bit,” says Sankar, “because I was feeding Axel a grain-free diet. It was Blue Buffalo, and he passed away suddenly. They did a chest X-ray, and they did say that he had an enlarged heart. I automatically thought that it was because of the grain-free diet.”

Following the investigation, industry experts have reported huge losses in sales for grain-free pet food in the U.S. and Canada. Before the FDA’s investigation in 2018, grain-free pet food sales were growing at an average annual rate of 8.4 per cent. However, by the end of 2019, the growth rate had reversed, and the sector was contracting at a yearly rate of 5.9 per cent. “Pet food is not usually a national news topic,” says Schulof, looking back on that time. “It’s rare for a pet food story to cross over into the mainstream. DCM did that.”

The FDA’s announcement of the investigation took many in the pet food industry by surprise. But those closest to the subject were mostly suspicious. “As you can imagine,” says Schulof, “there are all these brands that make grain-free pet food that are primed to be skeptical of this investigation, to be looking for anything that smells off.”

Here, Schulof’s experience as a litigator led him to file a Freedom of Information request with the FDA to get the internal records related to the DCM investigation. In early 2019, the government agency began sending him documents, a process that took three years to complete. “I started reviewing them,” he says, “and it became clear that there was stuff that had taken place that was non-public, fraudulent, and tied to specific bad actors. There were very specific things that folks did wrong that misled the FDA to launch this investigation, and it wasn’t publicly reported.”

In the U.S., almost half of pet owners admit that they have no idea how much their dog should weigh. More than ninety per cent of the clinically obese dogs in the United States belong to owners who wrongly believe their dogs are in average condition.

After reviewing the files, Schulof claims veterinarians at Tufts University allegedly bombarded the FDA with reports of DCM in dogs consuming grain-free diets to create a false link between the disease and grain-free dog food brands. He claims Hill’s used its extensive distribution network, including free veterinary education and incentive programs, to convince the public that grain-free diets were causing widespread health issues in dogs.

Given the significant role of cereal grains in many pet food recipes, Schulof suggests there is a clear conflict of interest in advancing research that suggests carbohydrates make dogs fat. Moreover, there is a clear incentive to produce research that discounts grain-free foods. The regulatory, scientific and academic communities significantly influence public perceptions.

Despite the success of companies like Mars Petcare and Hill’s Pet Nutrition, North America’s dog population has never been less healthy—experiencing increased rates of diseases. Schulof believes the state of our pet’s health has worsened since these companies built connections to veterinary research. “The notion that more than half of the dog owners in the county are either too stupid,” Schulof writes in Dogs, Dog Food, and Dogma, “to provide proper care for our fur babies strikes me as both fanciful and, frankly, insulting.”

Even though there has been no scientific link between grain-free diets and DCM, veterinarians safely rely on the fear-driven possibility that one could exist to dissuade customers from buying food elsewhere. If, as Schulof argues, digestible carbohydrates play a central role in causing canine obesity, then veterinarian-endorsed brands—despite their self-styled image as best aligned with veterinary health—would be largely responsible for North America’s canine obesity epidemic. Why, then, won’t veterinarians consider this new science?

Canada’s Kennel

Before Dr. Stuart Owen retired in 2021, clients at McGilvray Veterinary Hospital in Toronto frequently asked him what they should feed their pets, hoping that changing their diet might help them escape their present fate. But, to their disappointment, he would not give them a straight answer. “I would always get involved in their personal situation and then try to make some general recommendations, as opposed to saying, I think you should buy Royal Canin,” he says. “I just never did that.”

Regardless of these companies’ true intentions, a significant hurdle for many Canadian pet food firms remains establishing the same level of trust as their American competitors. “We want to be able to make sure that our pet food actually meets current, good manufacturing standards and that the pet food is appropriate for particular animals of their breed and species in that particular stage of life,” says Kris DeAngelo, associate director of Michigan State University’s Institute for Food Laws and Regulations. “The [U.S.] industry works with the FDA in terms of being able to craft those.”

Canada, on the other hand, is a different story. “You’ve got the Canadian Pet Food Manufacturers Association, but there aren’t standards coming in, even in terms of inspections for imports. You’re just relying on countries like the United States,” says DeAngelo.

An important legislative distinction between the United States and Canada is that the FDA considers pet food to be food, while the CFIA does not. For this reason, it is not protected under the same provisions or treated with the same care. “Having that very different definition of food means that they totally escape the same kind of regulation,” says DeAngelo. The absence of specific laws or regulations means there are no guarantees regarding the quality, protein sources, or calorie content of dog or cat food. Canada’s regulations cannot keep up with the increasingly complex pet food market. In a 2018 study that appeared in Canadian Veterinary Journal, studying Canadian-specific dry dog and cat food brands, only nine of twenty-seven foods met all nutrient content claims listed in their guaranteed analyses. The lack of nutritional standards and a pre-market product review for pet foods has left the Canadian industry susceptible to insufficient diet formulations and deceptive product marketing. Naturally, many pet owners have come to rely on American. products and compliance standards. Canada’s veterinary community has done so and is given little reason to stop.

“Historically, diets have definitely been carb heavy,” says Dr. Owen, “because it’s a lot more expensive to put protein into a diet. There’s been a tendency to put carbs in to get their calories and their [nutritional] requirements that way.” While certain brands use ingredients that may not be optimal, they are affordable for the average consumer.

“I am not comfortable telling every pet owner that the obstacle to pet ownership is money,” says Shoveller. “I don’t think that’s fair. The possession of pets enhances the quality of people’s lives. How do we tell a single mom with three kids that she can’t have a dog because she can’t afford it? That breaks my heart.”

Although Schulof and Dr. Owen can seemingly agree on this point, the difference lies in whether pet parents bear some responsibility. “A lot of the overweight issues come from animals being overfed in the first place,” says Dr. Owen. “I don’t think there’s much question about that. People tend to give their dogs lots of extra treats and they feed them a lot [more than needed]. I would say a lot of dogs, especially in Toronto, just don’t get that much activity.”

“It’s very hard as a professional to recommend a lot of the boutique diets as there is often not much science to back up their claims,” says Dr. Owen. “There are probably well over 1,000 available dog foods on the market. It’s impossible to know them all, so I only recommend diets, usually the big three, because of the research they’ve done. There’s no question that the large companies control the information, but I do believe it’s not like it was twenty-five years ago. I mean, it was either Hill’s or nothing.”

Grain-free Does Not Equal DCM

“I don’t know why there is a team grain and team grain-free out there,” says Sankar. “Different bodies process things differently—there’s no one-size-fits-all.” For that reason, there is no one miracle pet food diet or brand. In the U.S., almost half of pet owners admit that they have no idea how much their dog should weigh. More than ninety per cent of the clinically obese dogs in the United States belong to owners who wrongly believe their dogs are in average condition. The concerns over grains or grain-free overshadow the poor state of our animals today. The effort to promote a connection between grain-free diets and canine DCM shifted the public’s attention away from other significant diet-related health issues in dogs. Schulof wants to undo this and remove the blame from unsuspecting pet owners, burdened by sick pets, back onto the manufacturers who he believes made them ill in the first place. But along the way, problems related to canine health have become worse since traditional companies started influencing the veterinary community.

Pet parents should not be blamed for giving an extra treat now and then when the science behind the food is fundamentally corrupt and broken. Due to Canada’s lack of pet food regulation, U.S. pet food manufacturers influence the market and operate without accountability. Canada’s pet food regulations are outdated and insufficient, but because of the lack of federal laws, it has been challenging for consumers and veterinarians to regain trust in Canadian pet food companies. “At the end of the day,” says Sankar, “you can take the advice of somebody, but you still need to do your own research.”