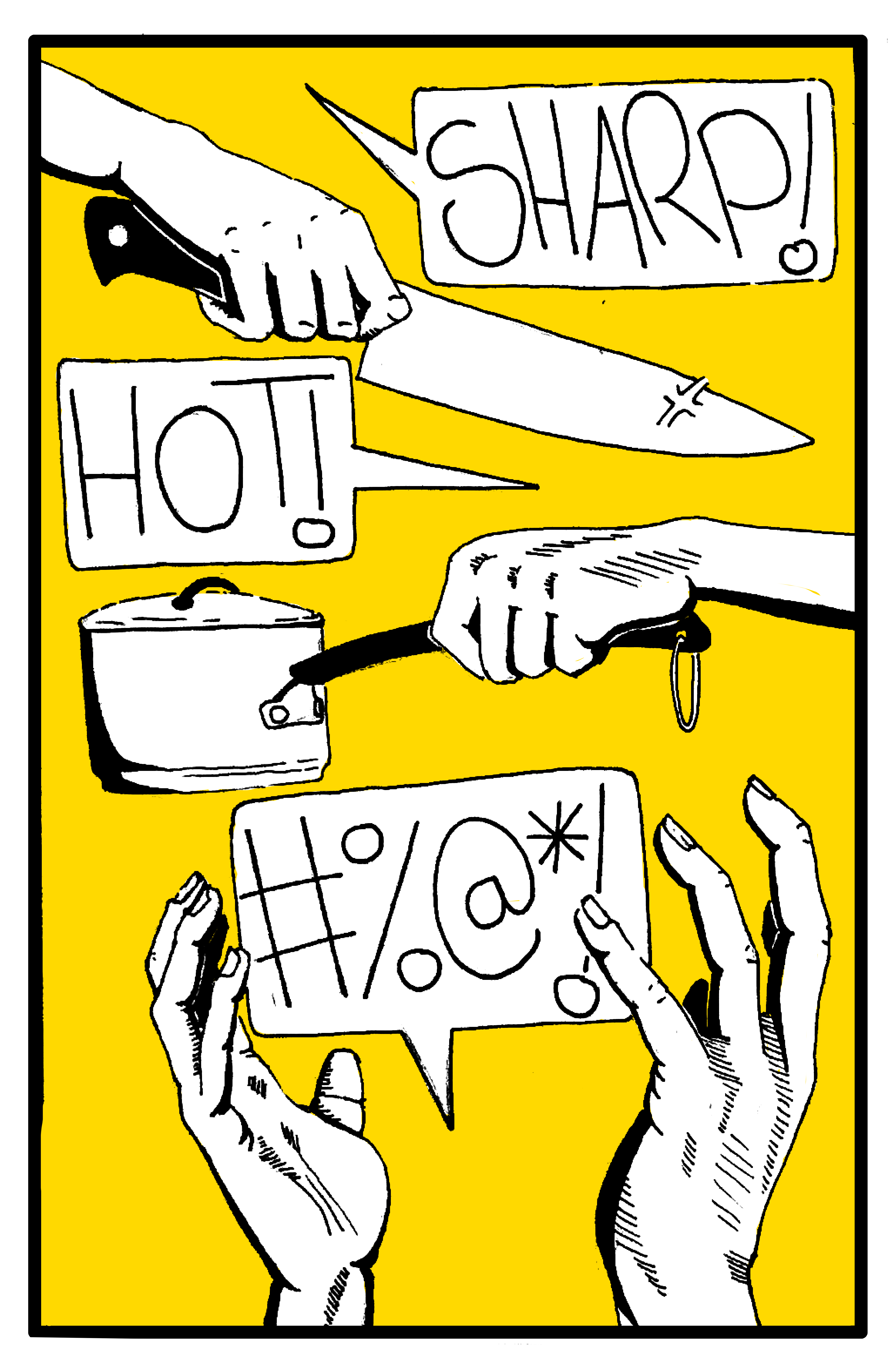

Professional cooks and servers have faced abuse on the job for decades. It’s time for change

BY HANNAH MERCANTI

ART BY S35

———————————————————–

It started as a part-time restaurant gig—a way to pay the bills. Five days a week at four p.m., twenty-year-old Yusra Khalil opened the doors to the gilded entrance of Verity, a membership-only women’s club in downtown Toronto.

She walked through the lobby, headed for the club’s restaurant, past the robotic smiles of the security guards and secretaries. Like Dante, she descended further into hell—in this case, the sparkling world of the bourgeoisie—before reaching the change rooms of George, one of Toronto’s premier fine-dining restaurants. Known for its “double-blind” tasting menu, each course is

customized according to the guest’s preferences, which can add up to twenty different original dishes. George offers diners up to ten courses for a maximum of $180, featuring signature dishes like fresh wagyu beef paired with artichokes and black olive caramel.

Upon arrival, Khalil donned her black button-up and crisp Banana Republic pants she’d invested in. She swivelled around to the mirror and slicked back her red curls into a tight, forehead-pulling ponytail, ready to prepare for the upcoming dinner service.

On a bustling Friday evening, George serves hundreds of guests. From the opening of the doors at 5:30 p.m. to the last slam in the early morning hours, server assistants like Khalil run around serving food, bussing tables, and ensuring the restaurant’s high standards are met. Executive chef Lorenzo Loseto cares deeply about the dishes he creates, with a special penchant for their presentation. Dreamy, elegant white plates seemingly float out of the kitchen with edible floral arrangements perched on each handcrafted dish.

Achieving this level of excellence requires food runners like Khalil to use their spare time to rub little circles of diluted white vinegar onto the freshly washed plates. This ensures the dishes are rid of any leftover water stains. And all employees, regardless of position, are expected to know the entire menu by heart, capable of describing the vision behind each of Loseto’s creations.

At the start of her shift, Khalil would look around for the other food runners, specifically her coworker Amelia, who served as Khalil’s secret source for insight about the kitchen’s mood—Amelia’s ex was friends with the chef. She needed to ask her a question that would determine the energy for the rest of her shift, and the moods of everyone else working that night. “Is Chef in a good mood?”

If Amelia answered yes, tension that Khalil wasn’t even aware of would lift off her shoulders. The service ahead would be nothing to stress over, and she might even crack a joke with Chef. But Amelia answered no, cold fear seeped into her veins, internalizing the stress she was about to endure. When Chef was in a bad mood, the environment was different. No chatting in the kitchen. No wrong tables. And definitely no backtalk. The panic induced was not in vain—they were doing what it took to make it through a shift.

As service workers and watchers of kitchen dramas like The Bear might know, abusive work practices are common in the restaurant industry. From chefs having their wounds forcibly cauterizing on stove tops to burning each other’s hands in the fryers for “fun,” research shows that work practices that are considered normal in kitchens—which, in many other contexts, would be regarded as abusive or hostile—are accepted or even expected by many restaurant chefs. In extreme cases, chefs may believe they have to suffer to learn, which ends up defining their entire professional identity.

The line isn’t drawn at physical violence, either. As female chefs and servers are loathe to report, there is an obvious locker-room energy in largely male-dominated kitchens. Jen Agg, a Toronto-based restaurateur, writes that along with the assumption that lower-level chefs follow orders, new chefs feel obligated to be a team players, which can manifest in a variety of unsavoury ways. Witnessing a head chef make sexual comments about a female employee can influence the entire culture in the kitchen, essentially giving others permission to mimic abusive behaviour.

From being followed into the walk-in cooler for a ‘little kiss’ to having her ass grabbed, nothing surprised Taylor.

Female chefs and servers have to listen to male coworkers make sexist or sexual comments. Gay men and women have to endure their lives and identities being transformed into workplace jokes. Even straight, white men can’t escape the abuse that permeates kitchen culture. Intense service periods and high demands on chefs to quickly dish out meals lead to violent outbursts, which have unfortunately become imbued in kitchen culture.

If You Can’t Take the Heat . . .

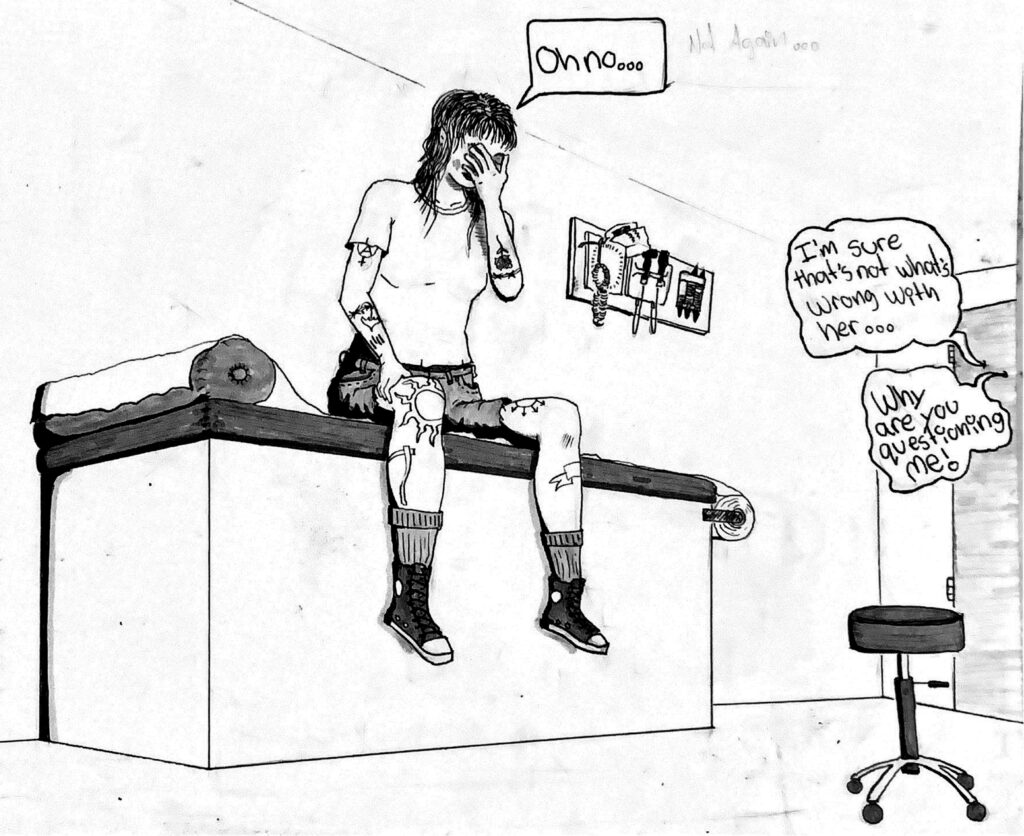

Khalil’s voice catches as she recalls the incident that made her quit her job at George. One day, while doing a quick change, she noticed something unsavoury on her Banana Republic pants. A little hole looked back at her from the mirror, right on her butt.

Khalil wasn’t a rookie. She understood what the expectations were in fine dining, and it certainly wasn’t having a hole in your pants. As sweat began to bead on her forehead, she had Amelia check if the hole was noticeable. As she flashed her a confident thumbs-up, Khalil figured she was in the clear. So, she slipped them on and went about her tasks, happy to put the hole—and the fact that she wouldn’t have to cash in her tips to buy new pants—in the back of her head for the night. But she wasn’t that lucky. “I was walking up the stairs and my manager, the front-of-house manager, was behind me and said, ‘Yusra, I can see your butt!’” She went cold, but left it for the time being, and continued to work her shift. Until he brought it up again. And again. Finally, she couldn’t ignore him any longer. She took a deep breath and asked if she could talk to him.

As they entered the office, Khalil quickly jumped to her defence. She told him that she wouldn’t be spoken to like that, especially not at work. Her manager responded by smirking and saying, “I’ll stop when you buy new pants.”

Not every woman working in restaurants experiences blatant harassment like Khalil did, though many report experiencing its misogynistic culture. The main reason men tend to dominate professional kitchens is that they are thought to possess the skills and resilience that women do not. But it may be less about qualifications than it is about systemic workplace sexism.

Rachel Taylor, a chef who has been cooking since childhood and working in restaurants since she graduated culinary school, has witnessed a variety of abuses. From being followed into the walk-in cooler for a “little kiss” to having her ass grabbed, nothing surprised Taylor. And like many other young chefs, she wanted to fit in and be liked by her coworkers, which meant not reporting anyone for sexual misconduct or other wrongdoings.

It isn’t uncommon for women in the culinary industry to be treated as less than their male colleagues, despite women historically doing the majority of domestic cooking. It doesn’t matter where they rank in the hierarchy, women are frequently relegated to tasks considered less prestigious, such as preparing vegetables or assembling pastries—even in restaurants owned by women.

Silenced

When she left for her exchange in the tiny Italian town of Piedmont, Taylor worked under Massimiliano Musso, the chef at the Michelin-star–rated restaurant and hotel Ca Vittoria. During her time there, she remembers him speaking to her only once: telling her to work “nice and faster.” During dinner services, while the team scrambled about their stations to impress guests and satiate the chef, Musso wasn’t exactly practicing what he preached. Instead, he could be found at the back, screaming wildly at his elderly grandmother, who was washing dishes for them.

Rejecting anything, speaking up, or complaining is unacceptable. When faced with the choice of either reporting an unsavoury coworker or losing their job and potentially never working in the industry again, many prefer to just shut up and take it. This is especially true since the majority of the victims are already disadvantaged in these environments, with women and queer people taking a significant brunt of the abuse. The fear of being blacklisted from the culinary world, or having their career sufficiently ended by calling out an influential person in the industry, is enough to keep them quiet almost to the point of protecting the system. Consequently, the abuse persists.

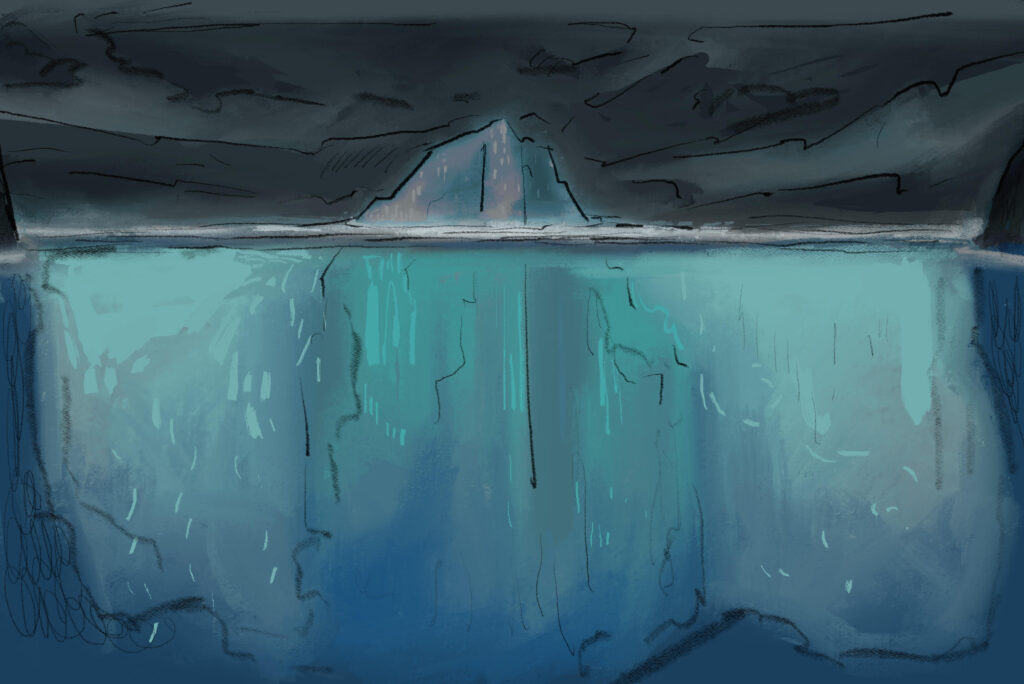

Research has shown that the brigade set-up—the traditional organization of modern high-end kitchens—is not at all beneficial to the mental health of the chefs or staff working in these kitchens. On the contrary, the brigade directly contributes to bullying and psychological harassment, prioritizing structure and efficiency over worker needs. The inherently rigid, uncompromising demands of the brigade have been linked to the stress, pressure, and tyrannical environment common in modern restaurants.

Weary Waiters

Kaitlynn Lewis stood at the back door of Amica Stoney Creek. She was waitressing at the chain retirement home, which boasted a variety of “five-star” amenities, including daily fine-dining experiences for residents.

Wearing a creamy white button-up, black vest, and ascot, Lewis unlocked the backdoor to the building’s staff entrance with her key fob. Apprehensively, she opened her iPhone and looked up the day’s schedule. Slowly, she read to herself, crossed her fingers, hoping she wasn’t scheduled with the sous chef. “I had so much anxiety about it,” she says. It had been a week or so since they had worked together, and she hoped her good luck would continue and creep into this week. Unfortunately, as she read, her hands began to shake and her breathing quickened. They were both scheduled on the same day.

In Lewis’s experience, the energy in the kitchen is typically determined by the supervisors and cooks, and less by the waiters themselves. “I would be berated or made fun of or just get in trouble because that was something [the sous chef] did often.” Lewis wasn’t the only one targeted. Each server experienced it to some degree, but in Lewis’s memory, she got it “the worst.” Eventually, it got to the point where her mental health was being negatively affected outside of work. “I had already been in counselling for unrelated reasons, but every single time I went to therapy, I would be talking about the sous chef.”

A chill penetrated Lewis’s light blouse as she entered the industrial walk-in fridge, which housed everything from diabetic-friendly, sugar-free Jell-O to bulk containers of bread-and-butter pickles. The frigid air hummed around her, and as Lewis got her bearings, she remembered what she came in for in the first place: a piece of cake for a resident who hadn’t been interested in the dessert offered that night. She searched through the white cardboard boxes until, finally, she landed on the right one. Quickly, she slipped the piece out and onto a cake plate, whisking the dessert away to be served.

Unless you are at the top of the food chain, your power is almost none, especially if you’re just a line cook.

Little did she know, tension was brewing in the kitchen behind her. When she walked back through the double doors, there he was, waiting for her in a stained chef’s jacket. He stood there, imposing and holding an empty, white cardboard box.

“Why would you put this back?” He yelled. “It’s empty!”

As the kitchen swirled with noise around them, Lewis was taken aback. “He was implying that I did it and that it was on purpose, and I was just being lazy.” In the background, plates destined to arrive at her tables sat on the metallic pass, being momentarily kept warm by the finger-burning heating elements installed in the kitchen. Dumbfounded, she began formulating a response that would hopefully satisfy the sous chef and get him out of her face. “Well, sorry,” she stuttered, “but I didn’t do that.” Grumbling, he walked away, leaving Lewis to replace the box.

This was more than just a single bad day. It was built into the culture of Lewis’s workplace, like so many other kitchens. In a study about suffering in kitchens, the concept of enduring physical harm as an expression of identity came up frequently with the interviewed chefs. One went so far as to say, “The staff should be able to sustain some level of abuse, you know, because that’s just the job.”

Behind the Line

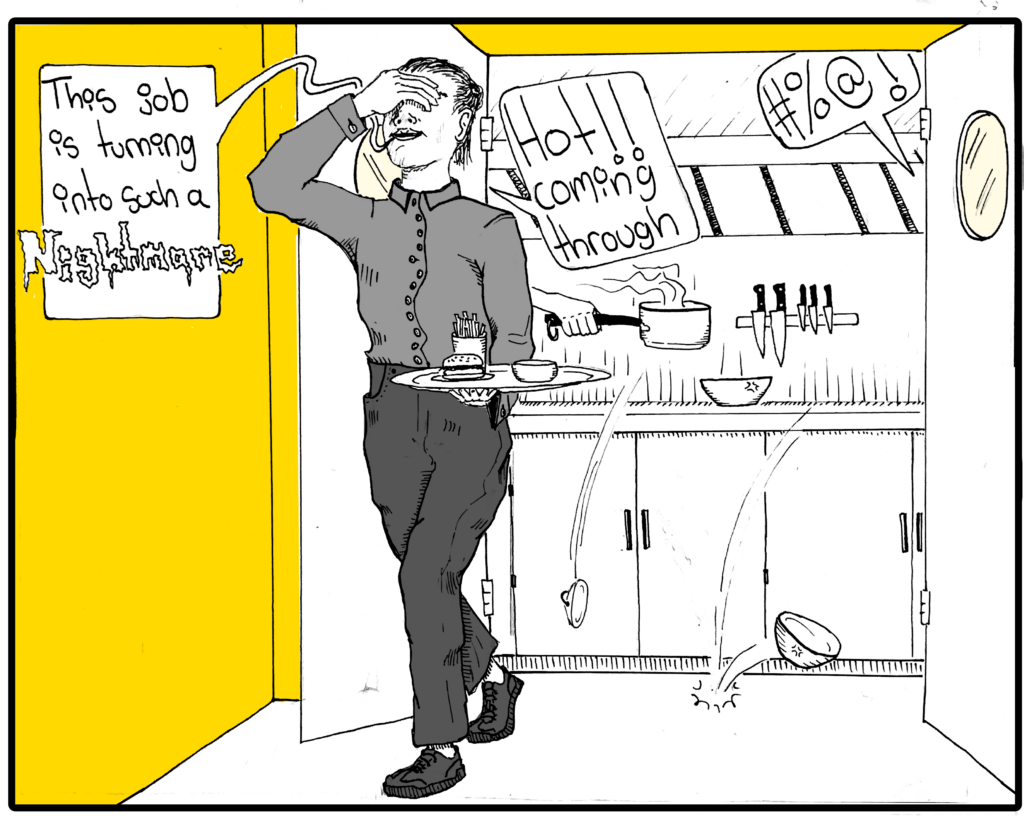

When Michael Karant was employed at Marbl, a lush, modern American steakhouse fittingly decorated with tons of marble, he existed as a jack-of-all-trades. He’d worked almost every position: dishwasher, busser, chef. Karant recalls the prep days where he and the other cooks made their way through pre-service tasks. This always prompted what seemed like incessant torment from their head chef. “He would say, ‘Why are you not doing this? Why are you taking so long on this? Why are you not done that yet?’”

“If you’ve ever worked in a kitchen, you do understand just how exhausting of a job it is,” Karant continues. Often, chefs work significantly more than the standard forty-hour week. And if they work in a busy kitchen, there is constant pressure to get things done perfectly the first time. “You’re working in a hot, dirty environment. People will get burns and cuts—it’s a daily thing—and you just expect everything to be done as you would have it done. And when it’s not, you just get frustrated.”

Kitchens seldom provide chefs with windows, personal space, or control over the temperature. Acknowledging that environment, where chefs are overworked, overstimulated, and burnt out, Karant sympathizes with the toll it can have on those leading the kitchen. Although he understands why chefs lose their tempers, he says it’s not the only way to manage emotions in a kitchen. “If you have a chef that you know will be firm when needed, you will just do your job calmly,” he says. “You won’t be afraid of getting yelled at.”

A study conducted at Cardiff University found that this environment—chefs separated from the general public, working long hours, spending the majority of their time at the restaurant—creates a “parallel moral universe” where abuse and violence are the expected and accepted norm. The chefs interviewed in the study reported that they would never endure the abuse they face in kitchens in any normal scenario, but once they walk through those swinging doors, all bets are off.

David Courpasson, a French sociology professor located in Lyon, says in an article for The Guardian that people who want to stop bullying in kitchens should make the swap from the cramped, isolated brigade to an open-concept kitchen. According to another chef interviewed for the same article, in open kitchens, diners can see what the chefs are doing and hear what they’re saying. Because of this, chefs have to maintain a level of cool-headedness and professionalism that simply isn’t required in the traditional kitchen environment.

Matt Davis, a chef with thirteen years of culinary experience, echoes this idea. As wrong as harassment and verbal abuse is, he believes it stems from the intensity of the job. “In the rush of things, where you’re firing fifteen plates at one time and everybody’s stressed, the pressure is extremely high. And then people will yell,” Davis says. He recalls life in his early twenties, which revolved completely around the restaurants he worked in. “Unless you are at the top of the food chain, your power is almost none, especially if you’re just a line cook,” he says. “If you’re not a sous chef or chef, there’s not much you can do. You can take it, shut up, and deal with it.”

While group therapy may not be a realistic answer for most kitchens, other solutions include having an official policy on harassment in kitchens.

Once you’re there almost every day, the kitchen and the people in it have a way of becoming central to your life. Even on his precious two days off, Davis would sometimes go to the restaurant to visit coworkers. In many restaurants, servers and chefs alike are expected to pull long shifts that frequently creep into the early hours of the mornings. “It was all I would do,” he says. “My life revolved completely around the restaurant.”

Although harassment may be embedded in kitchen culture, there are solutions. “All brigades should have mandatory group therapy,” Davis says, laughing. A lot of the time, he says, disagreement in kitchens simply comes from miscommunication, or no communication at all. In the heart of a busy service, chefs are more likely to yell and get angry than to communicate and discuss what is going on, which seems to be the larger issue. “There’s not a lot of people I know that stay calm through and through,” he says. “We expect a lot of chefs and cooks to perform way above average efficiency when, a lot of the time, it’s not reasonable.” When a five-person team is asked to present 400 perfect dishes a night, he says, it’s more likely than not that someone will be pushed to their breaking point.

While group therapy may not be a realistic answer for most kitchens, other solutions include having an official policy on harassment in kitchens. Many smaller restaurants are unlikely to have full-blown human-resources departments, which could help in setting policy that outlines acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. As well, chef/instructor Lucy Godoy notes that training is a major part of solving this problem. “This is where culinary education comes in,” she says, “to foster a new generation that welcomes critical thinking and a much kinder kitchen environment.”

Out of Sight

In the year since she left George, Khalil has all but abandoned the world of fine dining. She’s a photographer and has been practicing her craft for years now. Initially, she was energized and enthusiastic about her chef career. She figured she could practice on the colourful and extravagant dishes in her workplace. That dream has now been put on the back burner.

Khalil sits in her room typing as her cat contentedly purrs on her bed. “I did enjoy it,” she insists. “We spent so much time there, and we were like a family.” She likens it to Stockholm Syndrome, saying, “I loved everyone because I was there all the time.” Nevertheless, her once well-used button-up shirt and ripped pants sit at the back of her dresser, collecting dust.