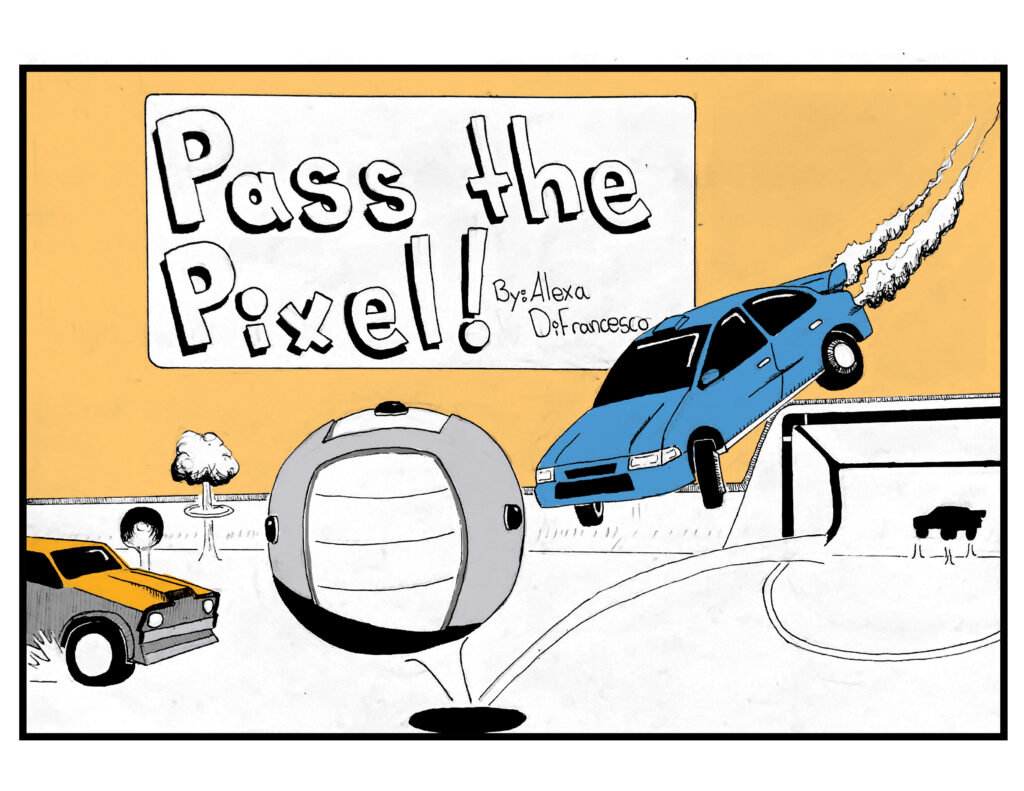

How college players cash in on the expanding Rocket League industry

BY ALEXA DIFRANCESCO

ART BY S35

———————————————————–

Making Cars Fly

If you’ve ever been in a room with flying cars, you’ll know the air is humid and there are a lot of potato chips. Such a place exists in Windsor, Ontario at St. Clair College. Once a year around mid-March, you can spot groups of twenty-somethings huddled over computer screens, trying to make cars fly. They do this, not for invention or to save the day, but for an even more noble cause: to chase a ball.

This morning, there are around fifty of us. Players are dressed in running pants, jerseys, and sweaters that boast their school’s emblem. Media teams wear black and carry professional cameras. Newscasters wear button-up shirts and dress shoes, although the Twitch stream they’ll speak on later won’t show their feet. “The Americans are stopped at the border!” someone yelps from across the room, taking shots of an energy drink.

The creator of this chaos is Rocket League, a video game that is essentially indoor soccer in five-minute rounds. It has elements reminiscent of a demolition derby, granting players the ability to jump mid-air, pick up speed boosts when driving over marked spaces on the field, and destroy cars they collide with. Working in teams of three in this tournament, players hit a ball that’s much larger than their cars toward their opponent’s net to score goals.

I’ve come to St. Clair to support Durham College’s Rocket League team, Durham Lords, which consists of professional players Daniel “jordan” Bholla, Alexis “Xocion” Guyennon, and my boyfriend, Mervyn-Dallas “Wildfire” Smith. It’s an achievement in itself that they’re good enough to be invited to today’s tournament. Although there are more than ten varsity teams in the province, only two others were asked to play in this tournament: Conestoga College and St. Clair itself. Today, they’ll compete against five of the best teams North America has to offer, the furthest travelling all the way from Ohio. The prize fund? A modest $2,650.

A decade ago, a tournament like this wouldn’t be possible. At the time, Rocket League was a newcomer to the esports scene. The game was released publicly in 2015 as a sequel to the popular game Battle-Cars, but when the Rocket League’s San Diego-based developer, Psyonix, observed the popularity of matches on live-streaming platforms, the company marketed it towards esports.

When Rocket League went free-to-play in 2020—from its original price of twenty dollars, the game’s number of players spiked. Although Rocket League no longer lets players see how many registered users it has, it offers a one-word status to measure how many players are online at a given time. The current word? “Amazing.”

It is amazing. With its unchanged “E for Everyone” rating, Rocket League has birthed a new wave of esports hype. This family-friendly appeal brings in sponsorships from brands like 7-Eleven, Ford, BMW, Lamborghini, and Nissan. The most popular global annual Rocket League tournament, Rocket League Championship Series (RLCS), reached a monumental peak in 2023, racking up just under half a million online viewers. Even the Rocket League betting scene is hot, featured on popular betting websites like GGBet and Thunderpick.

Unlike traditional sports, all of Rocket League’s best athletes are college students or people not old enough to be in college. To them, Rocket League is a solace. Their tournament rooms are light and clean, and, at first thought, so are their reputations. They’re role models, in the scene for cash and fifteen minutes of fame, but to be inspirational too. To them, this tournament at St. Clair is a paradise, an avenue to finally meet the people they’ve played with online for years. “Everyone talks to each other whether they win or lose,” Smith says as he sets up his computer. “There aren’t any friend cliques. No one’s enemies.”

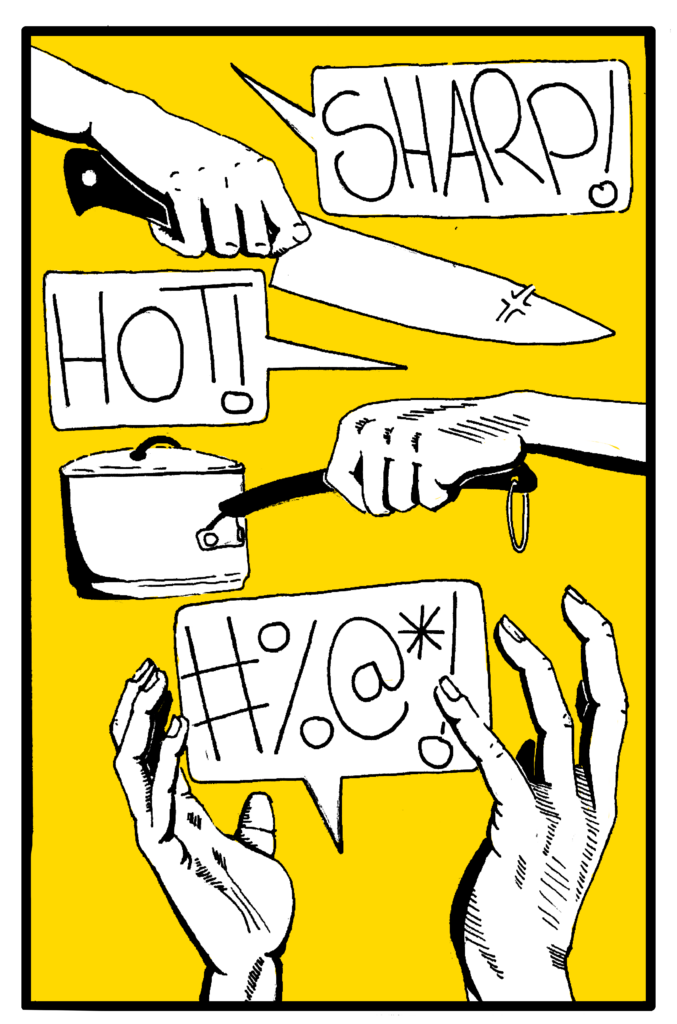

A player from an opposing team approaches Smith as he says this, shoving him into a desk. Smith’s arms hit the keyboard in front of him, hard enough that there are angry red marks on his forearms when he lifts them. His opponent sneers, “You 400-pound, chip-eating, fat fuck.”

The Driver’s Gambit

NTwo luxury vehicles meet in the middle of the midnight sky. They bounce off the tall ceiling netting and crash onto the field below them, landing on fluorescent green stems. Of course, they’re not dented after the crash—these are supersonic acrobatic rocket-powered battle cars, with octanes painted rich shades of red in patterns comparable to a turtle shell. They have black tinted windows, crisp white Nike swoops on their hoods and the Team Canada’s 2018 FIFA World Cup emblem painted onto their doorless sides. Their engines sometimes sit on their roofs. The cars become fragments, and then just disappear. They’ve almost crashed head-on, but their drivers aren’t worried. In game, there’s no hefty insurance premiums.

Rocket League players have years of professional, virtual driving experience. To avoid crashes, they have to rely on their instincts. They’ve memorized their vehicles’ function, which includes shortcuts to different skills. They trust that their instincts will protect them, even in in-game accidents like fiery car crashes. Giving up control is even easier because they’ve customized their cars’ gears.

Most Rocket League players can play on Xbox, Playstation, Nintendo Switch, or PC. Professionals play on PC, where the cars are controlled by keyboards. Look at the keyboard on the device you’re reading this story on. Drag your finger along the top row of letters, starting at W. Skip over E, and stop at Y. Try again in the second row, but stop at F. But find a way to reach N, because it’s involved too. This is what it takes to make a car drive, but only with your left hand. Your right hand grips your mouse. Left button, right button, wheel. Jump, boost, rear view. Now, your car’s flying. But don’t look down on your moments of doubt. Your eyes need to always follow the ball or the other team could snatch it from you.

These nitpicky mechanics are what separate Rocket League from other video games. In Call of Duty, for example, Guyennon says that players memorize mechanics that will transfer over to other gun games. But in Rocket League, athletes learn everything from scratch without taking away any transferable skills.

“It’s so hard to perfect that it leaves you so much room to improve at all times,” says Guyennon. One summer, he spent two hours a day practicing flip resets, a trick that involves all four car wheels hitting a surface to regain a flip mid-flight. To master the skill, Guyennon watched YouTube videos of professional players’ gameplay. “Using repetition in training is the best way to improve at the game,” he says. “I would watch, then go into training and spend hours just replicating things that they would do in game.”

Because Rocket League mechanics are constantly evolving, this learning curve continues even when players go professional, like Guyennon eventually did. It’s this learning curve that has convinced some players that Rocket League transcends the difficulty of other video games. In fact, they consider their skill to be at the calibre of chess masters. Yes, chess, the centuries-old game whose gameplay has sprouted a field within psychology and whose move combinations are described in The New Yorker as “dizzying, more than the number of atoms in the universe.” A YouTube video by Bard’s base camp compares Rocket League gameplay to traditional chess strategy. “I play both Chess and Rocket League . . . RL helps me with the visualization of moves in Chess multiple moves into the future,” writes a Redditor. Someone online estimates that, to become a Rocket League professional player, the average person would have to dedicate 17,000 hours to the game, as opposed to the 10,000 hours needed to be a chess GrandMaster.

“Chess and Rocket League are both decision-based games, but Rocket League has mechanics that need to be mastered, not only decision making, which makes it more difficult,” a Redditor agrees.

Their comment is met with upvotes.

Victory for Bholla

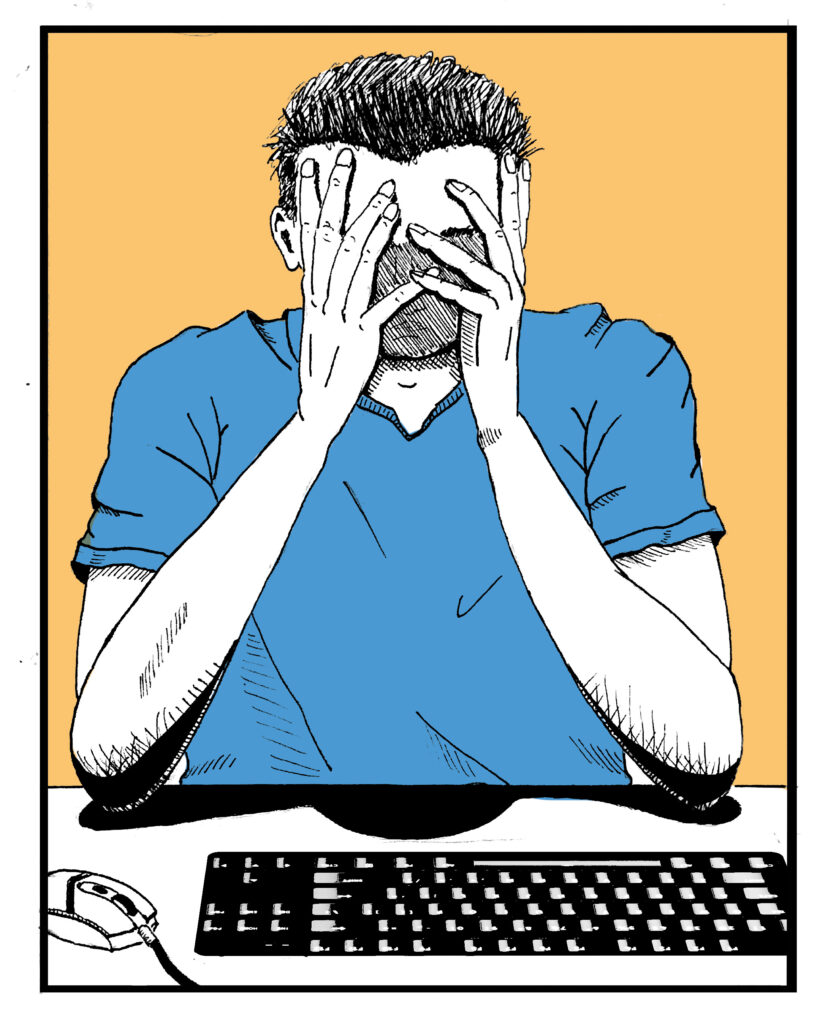

Bholla sits in the dark in front of his computer. His head is buried in his hands and his heart is pounding. There’s no one around but a select group of friends and teammates who are on a Discord call, occasionally yelling or grunting. It’s better this way. Bholla doesn’t want anyone physically in the room to witness his agony if the game doesn’t go his way.

The year is 2020, and Bholla is watching the championship round of Rocket League Rival Series (RRLS), North America’s most elite junior Rocket League tournament. Bholla and his team finished their season ranked first, but barely, from a points system. The second-ranked team, which trails only a few points behind Bholla, are finishing their last game. Their defeat would send Bholla’s team to win the tournament—and its modest $67,000 USD prize pool, enough for a downpayment on a house. It would also promote them to RLCS, a professional league, making them a professional team. Their victory would send Bholla’s team packing, leaving them to grieve and to prepare for another season of being just below professional play.

Game five. Overtime. The ball flies towards the netting. Bholla’s body shakes, his feet tapping against the cold floorboards beneath him. He holds his breath. He looks away, then zeroes in on the screen. Bholla is watching the second highest-seeded team play—if they score, they knock his team out of the victory spot. When the team he needs to win finally scores, his teammates’ roars are overwhelming. Bholla falls to his knees and cries tears of joy. Screams. He stays there, in the fetal position for five minutes, sobbing into his shirt.

For Bholla, it was more than a victory. A year earlier, he had dropped out of high school in hopes of pursuing Rocket League professionally. Initially, his family protested, even threatening to sell his gaming consoles, but Bholla became good fast. After a couple of months, after he showed his loved ones his first contract, and the dollar sign attached to it, they quickly became supportive. The 2020 victory solidified Bholla’s choice to gamble on himself. “It was so huge for me,” he says, “because I stopped going to school for this.”

After that win, Bholla’s life changed. At seventeen, he became the top Rocket League player in North America, accumulating an overall prize pool of $30,000 USD. Bholla would have won more tournaments, his coaches insist, if there were more skillful players on his teams. He got his own Liquipedia page, the esports equivalent of Wikipedia. At tournaments, excited strangers stop him as he’s about to play onstage to ask him for photographs or autographs. Fans message him, insisting that he inspired them to pursue Rocket League careers. If his big break hadn’t happened when COVID-19 was at its peak, Bholla would have been invited to compete in in-person competitions in Madrid, London, and Amsterdam.

After a few years of playing professionally full-time, it was time to go back to school. Bholla took two years to earn his high school diploma. Then, he contacted Durham College, a school in Oshawa, Ontario, which had previously reached out to him. He was signed to a full-ride scholarship within months. His mission? To put Durham College on the map.

Durham College’s esports teams are sponsored by Lenovo, a Chinese-American technology company currently worth about $13 billion, and Monster Energy, a multi-million-dollar energy drink company. With these deals, varsity players can expect branded mouse pads, water bottles, socks, sunglasses, bandanas, computer bags, and uniforms. In exchange, brands get access to student bodies that they can advertise to. Durham College esports manager Bill “Bluewinters” Ai says that building brand recognition amongst these students is “one of the biggest goals” for these companies. “We compete at a very high level,” Ai says, “ and our online presence can build connections.”

Smith remembers when he first got a sponsorship with Monster Energy through Durham College. Every month for two years, a case of twelve Monster Energy drinks was delivered to his doorstep. He watched from his window as a big black truck with the neon green Monster logo spray painted on its side approached his parents’ house. An unusual sight in Ajax, Ontario, it drew attention from his neighbours. “I felt like the GOAT,” Smith remembers. “I felt that I achieved something.”

“Do you think it’s worth it for these million-dollar companies to partner with you?” I ask him. “How much brand awareness can a college team bring them?”

“I have a lot of fans, so it’s worth it.” Smith says, shrugging. “I’d say I have about fifty.”

Training Grounds

Joel “ShadowR” Cresswell stands over a group of teenagers sweating through their t-shirts. He’s in Durham College’s Esports Arena, and it’s the first day of varsity Rocket League tryouts. He should be looking onscreen at the players’ gameplay, but he’s not. He doesn’t have to. He chose who would make the team weeks before tryouts even started.

Every year, approximately fifty students try out for the three-person collegiate Rocket League team. They’re begging for a chance to represent a team in a game they’ve played for years. “You can bring someone in who doesn’t know anything about video games, and they’d be able to understand that the cars go into the net by one team, and they need to win,” says Justin “Jcubed” Janulewicz, a caster. College esports, he thinks, have done a really good job of presenting video games in a professional manner to the public for the spectators. “It becomes a trickle-down effect. You have your kid who watches it, and they say, ‘I want to try playing Rocket League for my school.’”

To determine who makes the cut, colleges use a ranking system that orders players based on their end-game leaderboards. Ahead of tryouts, coaches use these systems to gauge the skill set of their prospective players. Then, they determine whether players with the highest skill sets fit the playstyle of the small team or if their playstyles mesh with existing varsity players. “But if we have a really standout player,” says Creeswell, “we’ll mix and match other team members based on how they fit into that.”.

“Chess and Rocket League are both decision-based games, but Rocket League has mechanics that need to be mastered, not only decision making, which makes it more difficult.”

– A Redditor

To help varsity players maintain the skills needed to compete at a high level, Ontario schools have built esports arenas on their campuses. The first was Lambton College in Sarnia, Ontario, which erected the Lambton College Esports Arena in 2017. In 2022, St. Clair made a historic $23 million investment into a 15,000-square-foot arena, sponsored by Nexus. In the same year, esports arenas have popped up in three other Ontario schools—Durham College, Conestoga College and Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU). Gaming computers, competition stages, broadcast studios, soundproof streaming rooms, and virtual reality lounges are just some of the training ground amenities players expect when playing for their school’s team.

Cresswell says these spaces are smart investments because they allow schools to train their teams to perform in high-stress environments. “When you’re competing in an in-person event with another team, your competition is physically sitting on the other side of the arena,” Cresswell says. “You might be used to people watching you online, but when people are physically watching you, you can really feel the eyeballs and have to keep composure.”

Janulewicz says it’s good to have verbally aggressive players in the Rocket League scene “because of how they get people riled up.” Janulewicz insists that onstage play is healthy because it forces players to own up to the insults they spew online. It’s common for players to scream at each other across the stage because of these insults. This, Janulewicz notes, is a cultural element of the game, “although there’s a limit of fighting players have to reach before we have to physically pull them apart.”

“It’s great to see a team hold their opponents accountable for playing overly confident,” he says. “It’s good to see teams rub their opponents’ faces in it when they beat them.”

Training Grounds

Joel “ShadowR” Cresswell stands over a group of teenagers sweating through their t-shirts. He’s in Durham College’s Esports Arena, and it’s the first day of varsity Rocket League tryouts. He should be looking onscreen at the players’ gameplay, but he’s not. He doesn’t have to. He chose who would make the team weeks before tryouts even started.

Every year, approximately fifty students try out for the three-person collegiate Rocket League team. They’re begging for a chance to represent a team in a game they’ve played for years. “You can bring someone in who doesn’t know anything about video games, and they’d be able to understand that the cars go into the net by one team, and they need to win,” says Justin “Jcubed” Janulewicz, a caster. College esports, he thinks, have done a really good job of presenting video games in a professional manner to the public for the spectators. “It becomes a trickle-down effect. You have your kid who watches it, and they say, ‘I want to try playing Rocket League for my school.’”

To determine who makes the cut, colleges use a ranking system that orders players based on their end-game leaderboards. Ahead of tryouts, coaches use these systems to gauge the skill set of their prospective players. Then, they determine whether players with the highest skill sets fit the playstyle of the small team or if their playstyles mesh with existing varsity players. “But if we have a really standout player,” says Creeswell, “we’ll mix and match other team members based on how they fit into that.”.

To help varsity players maintain the skills needed to compete at a high level, Ontario schools have built esports arenas on their campuses. The first was Lambton College in Sarnia, Ontario, which erected the Lambton College Esports Arena in 2017. In 2022, St. Clair made a historic $23 million investment into a 15,000-square-foot arena, sponsored by Nexus. In the same year, esports arenas have popped up in three other Ontario schools—Durham College, Conestoga College and Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU). Gaming computers, competition stages, broadcast studios, soundproof streaming rooms, and virtual reality lounges are just some of the training ground amenities players expect when playing for their school’s team.

Cresswell says these spaces are smart investments because they allow schools to train their teams to perform in high-stress environments. “When you’re competing in an in-person event with another team, your competition is physically sitting on the other side of the arena,” Cresswell says. “You might be used to people watching you online, but when people are physically watching you, you can really feel the eyeballs and have to keep composure.”

Janulewicz says it’s good to have verbally aggressive players in the Rocket League scene “because of how they get people riled up.” Janulewicz insists that onstage play is healthy because it forces players to own up to the insults they spew online. It’s common for players to scream at each other across the stage because of these insults. This, Janulewicz notes, is a cultural element of the game, “although there’s a limit of fighting players have to reach before we have to physically pull them apart.”

“It’s great to see a team hold their opponents accountable for playing overly confident,” he says. “It’s good to see teams rub their opponents’ faces in it when they beat them.”

Reinventing the Wheel?

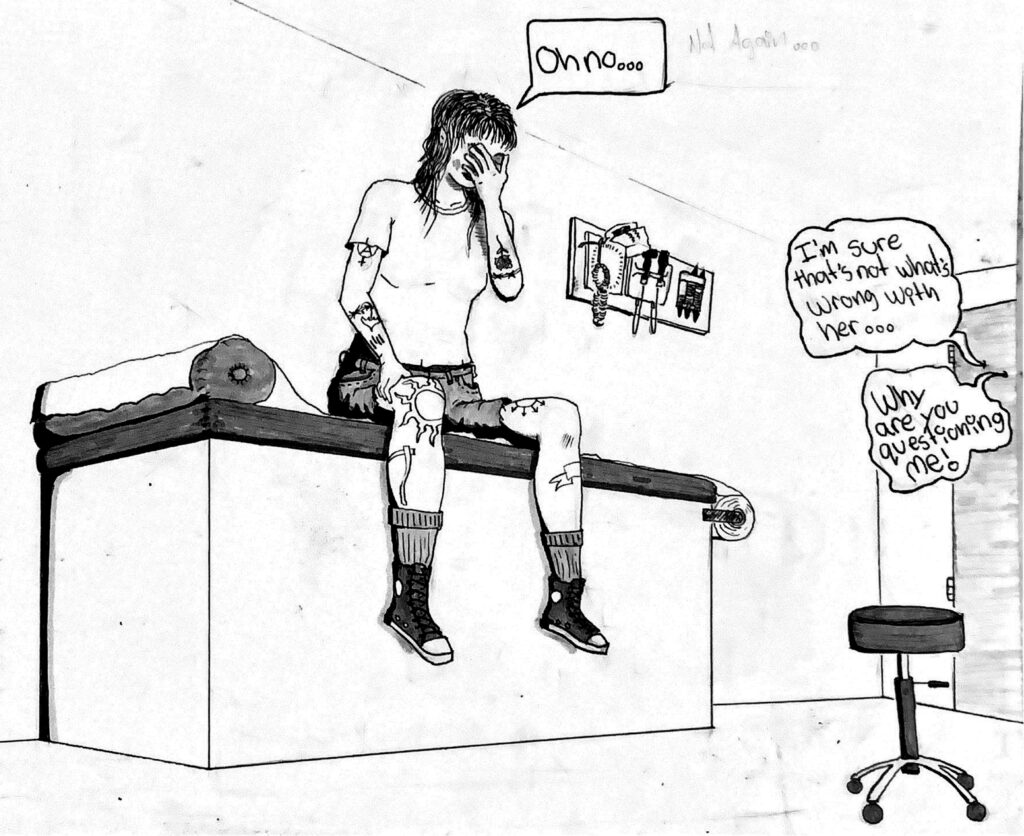

Jeff “DangerTaco” Skalamera sits in his bedroom in Chicago, Illinois, his cell phone pressed against his ear. The University of Illinois student is suffering from a major depression, which is about to reach its third year. He feels unsatisfied with the balance between his passion for Rocket League streaming and the responsibilities that come with the social psychology PhD program he’s enrolled in. His school is tired of it too. A few weeks earlier, when a program administrator demanded he make the choice between his doctorate or Rocket League the answer was simple: Rocket League. “They wanted me to do more, to be more productive on my own,” Skalamera remembers. “I told them, ‘I’m down to do whatever you guys need me to, but I don’t want to go above and beyond.’”

Now, on the phone, the administration team prohibits Skalamera from continuing with his preliminary exam, the precursor for his dissertation process. “The dean said, ‘We thought about what you said, and we do not find that acceptable,’” Skalamera recalls. He was also cut off from his university paycheque, which he got for being a teacher’s assistant and research assistant.

“I took a hard look at myself and decided that Rocket League was the calling point,” says Skalamera, who’d already authored studies published in prestigious journals like Oxford Academic. “I had lamented how graduate school took up so much of my time. I couldn’t really focus on producing Rocket League content the way I wanted to. I couldn’t focus on casting with energy every single day.”

“You can bring someone in who doesn’t know anything about video games, and they’d be able to understand that the cars go into the net by one team, and they need to win.”

– Justin “Jcubed” Janulewicz

Recently, Ontario has been encouraging kids to pursue esports full time, like Bholla and Skalamera did. In the past five years, esports business administration and marketing programs have popped up at colleges such as St. Clair, Lambton, Seneca, Mohawk, and Algoma. In 2022, the provincial government supported these programs in the form of $1 million over two years in scholarships for postsecondary students enrolled in them. While the numbers may seem high, the rationale behind these decisions is simple: the gaming industry is the largest segment of Canada’s entertainment industry, contributing more than $5.5 billion to the Canadian economy in 2021. In the same year, the gaming industry directly supported more than 55,000 full time jobs in Canada.

Now at the highest level of Rocket League casting in Canada, Skalamera relies on contracted freelance work to pay his rent. He works on average once a week because the broadcasts he works for aren’t budgeted. When younger people ask him for advice on how to incorporate Rocket League into their future careers, he gives them a reality check rather than encouraging them to follow his path: he says being an esport athlete is a “strange and not ultimately sustainable career for many people.”

Skalamera considers his advice greatly before offering it. He knows that the circumstances are tricky. If most players want to take the first step in making it big, they’re running out of time. The minimum age to play Rocket League is only thirteen, which gives players three years to get good at it before they can become a professional at age sixteen. The average age of professional Rocket League players to compete in RLCS, the highest level of competition, is eighteen. This younger demographic of players, bitterly dubbed “cracked kids” by older generations for their ability to rapidly adapt to Rocket League’s changing gameplay, often beat out older professionals on the scoreboards, forcing them into retirement in their early-twenties. “It’s easier for young kids that are thirteen to learn than it would be for an old professional to get better,” says Sebastien “Seb” Martin-Schultz, a Rocket League caster and content creator.

However, Andrew Fedurko, program coordinator for an esports administration program at Mohawk College in Hamilton, maintains that a career in Rocket League is sustainable for people of all ages. The key, he says, is the overlap between the existing sports entertainment market and esports’ entertainment market. Esports, he says, is the eighth largest industry in the world.

Fedurko brought up the gaming center at Toronto’s Exhibition Place grounds, which is owned by Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment. The centre hosts both sports tournaments and professional sports teams, like the Toronto Raptors Uprising team. “You’ve got this beautiful facility across the street from where Toronto FC play,” Fedurko says. “You’ve got the Toronto Marlies playing in the exact same building and you’ve got esports in there. Why are organizations that are worth billions of dollars exploring this? Because of that overlap in sports and esports.”

Even if Mohawk students decide that esports isn’t the career path for them, Fedurko says that the esports administration program was designed to give students skills that focus on communication, leadership and decision-making, all of which are transferable to other business sectors. These skills include managing professional teams, market research, interpreting analytics, social media marketing, and producing gaming events. If students decide to stick with esports, they aren’t just limited to becoming professional players at graduation. Mohawk’s program teaches its students how to become managers, broadcasters, video and audio mixers, script writers, and more after graduation.

As for the shape of the esports industry, Fedurko insists that we’re in the middle of an esports winter, where a lot of the larger companies have seen layoffs because they’re not yet sure of how many roles they need. “That’s really healthy, actually, because the business model wasn’t sustainable,” says Fedurko, comparing the industry to cryptocurrency. When everyone invests in it, the value of it increases to a higher level which will at some point come down. “It’s sorting itself out so we can sustainably grow into whatever the next five or ten years brings,” says Fedurko, “which is definitely going to be something that expands.”

Another Loveable, Stupid Car Game

After a horrifying loss to a high-ranked American team, the once almighty Durham College players, who, hours before, fearlessly chanted, “Put Durham College on the map!” are ushered upstairs by Ai. There, they’re given a talk similar to which a TikTok parent would give their toddler for doing something wrong, speaking to a videographer in St. Clair’s student learning commons. To the video camera, they solemnly reflect on what prevented their path to victory. The video will be played at the next esports department meeting to reassure administrators that their funds spent on the players was a wise choice because the players will learn from this mistake. These funds provided a $250 lunch allowance and four rooms in a five-star hotel for a night in a city that was a short four-hour drive away.

Another content creator from St. Clair’s media team asks to join the scene. His supervisors have tasked him with assembling a media package to recap the tournament. Students who are using the commons to study look on in short-lasting horror and bewilderment before they become occupied with studying for upcoming exams. Although I’ve brought my camera with me, I feel scummy recording, as if I was a tabloid capitalizing off of someone’s misfortune.

The players are shockingly candid when interviewed. Smith slouches against the support of the couch he sits on, meekly glancing at the cameraman, a hired student who props a professional video recorder against his hip. He grins at Cresswell, who makes the occasional face at him from behind the camera and declines when Ai asks him to 1v1 later that night. Guyennon stares into his lap, repeating a chorus of “ums” and “uhs,” presumably regretting taking a chance on a team like Durham. It’s only Bholla, with his years of professional media training, who looks fearlessly at the camera and proclaims that Durham will be on the map in their next tournament, in Montreal. They will get a limousine bus for transportation, free accommodations and a $150 meal budget for the weekend.

But, as we walk back to the parking lot at the end of a twelve-hour day focused on looking at monitors, Bholla’s media training slips away. “I feel like I’m wasting my life away when all I do is sit in my room all day and think of ways to improve in game,” he says. “I want to enjoy playing. What good is it when we win everything, but nobody has a good time?”