After a fifty-year nursing career, Joanne Wilkinson left friends and family behind to pursue her acting dreams

BY BRIDGET STRINGER-HOLDEN

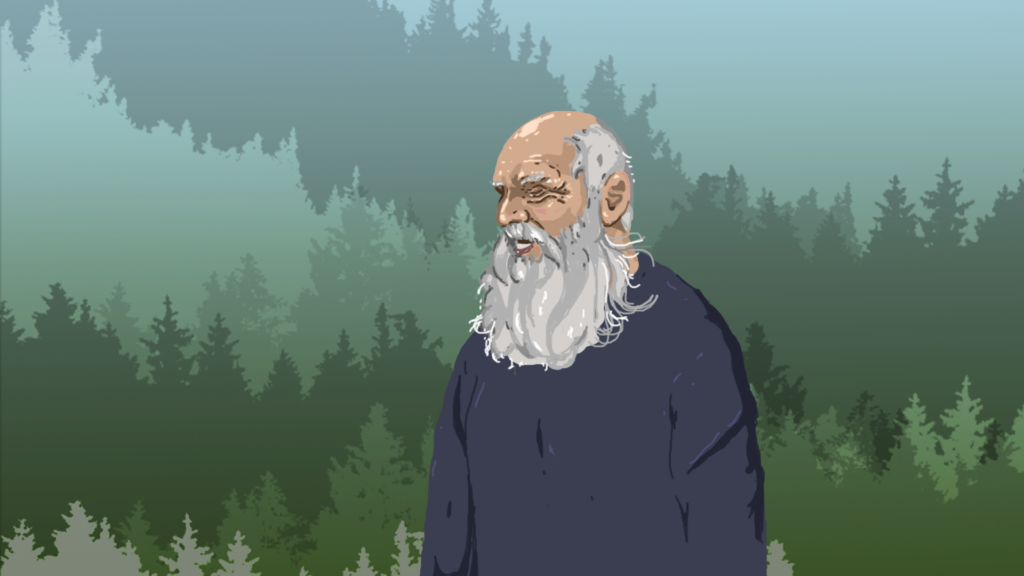

ART BY JOSHUA BEN JOSEPH

———————————————————–

In 1985, thirty-nine year old Joanne Wilkinson stood in the wings instead of centre stage. As a nurse in the Kootenay mountain town of Kimberley, B.C., she had gotten involved with the local community theatre a few months earlier, creating costumes for her teenage son, Miles. At six-foot-three, he was too tall for most costumes, so she learned to adjust them for him. Eventually, she began helping out with other costumes.

For this performance of Cinderella, Wilkinson designed the lead character’s gown out of a thrifted wedding dress. On dress rehearsal day, she stood by in case the outfit needed final adjustments.

The main cast was rehearsing the ballroom scene—where Cinderella finally dances with the prince— when the show’s director suddenly paused. There was no one at the ball. There weren’t enough dancers. On a whim, Wilkinson volunteered. Moments later, she found herself descending the prop stairs to the stage, turning around into the bright stage lights. This is fun, she thought. I love this.

She had no idea that this Cinderella story would change her life—and career—three decades later, when she was seventy-one.

Choosing a Career

In Grade 11, Wilkinson visited her guidance counsellor at Kitsilano High School in Vancouver, B.C., to ask what her career options were. “I was told I could be a nurse, a secretary, or a teacher,” she recalls. It was a common suggestion to young women in the mid-1960s—Wilkinson’s older sister had already been pushed into teaching, despite wanting to pursue a career in fashion design.

Wilkinson decided she’d become a nurse. It was a process of elimination, not passion: she couldn’t type, so secretary was out of the question, and she didn’t want to follow in her sister’s footsteps. “If I look back on it,” she says, “I’d have been a palaeontologist and dug up dinosaur bones.” But she didn’t know that was an option back then.

After graduating from the Vancouver General Hospital School of Nursing in 1967, Wilkinson first worked in coronary care, taking care of people who had suffered heart attacks. After that, she moved between medical departments, working where she was needed the most. She enjoyed working in surgery and spent a lot of time in the intensive care unit before she had her first child, Miles.

“I’m getting older, and if I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it. I won’t be brave enough to do it.”

Wilkinson quit full-time nursing to stay home and raise her family. After a few years of getting used to parenthood, she started to provide private home care services. This is when Wilkinson’s Cinderella moment happened — after that, she started acting in community theatre.

Wilkinson auditioned for the next play put on by her community theatre, Weekend Comedy, and landed the leading role. She went on to star in The Dixie Swim Club, Calendar Girls, On Golden Pond, and to play Morgana in King Arthur—all while nursing full-time.

In 2017, after a fifty-year career, she decided to stop nursing. At the close of her career, she was working as the director of nursing at Invermere Hospital in B.C. But instead of slowly retiring, she chose to pursue a full-time career in professional acting.“I put a lot of thought into it,” Wilkinson says. “I thought, ‘No, at some point you have to do what works for you.’ I didn’t want to do the conventional retirement thing. I wanted to do something fun and creative.”

Ultimately, it was her brother who helped her feel more confident taking the risk. “His philosophy was to live in the moment—now is what’s important,” she says. “That’s what pushed me to go because I thought: I’m getting older, and if I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it. I won’t be brave enough to do it.”

She also spoke with her husband and both of her sons, who were already living on their own. “I said, ‘I’m not leaving my husband, but I’m leaving Kimberley for a while,’” she recalls. “They were very excited and supportive because who else’s mum does that kind of thing?”

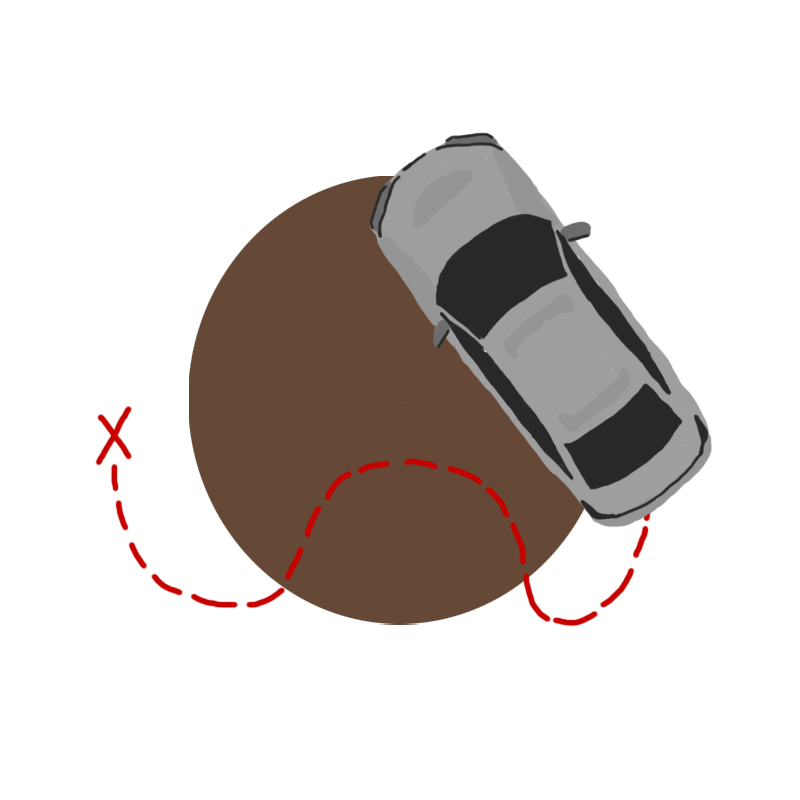

Coincidentally, age seventy-one is also when federal Registered Retirement Savings Plans must start to be withdrawn. Wilkinson took some of this money, packed her things into a silver Honda Sedan, and, on a crisp spring day in April, headed for her old hometown of Vancouver. She turned out of her long, gravel driveway and followed the road out onto the Kimberley Highway toward the neighbouring town. “When I drove to Cranbrook, it was like, ‘You drive to Cranbrook all the time,’ and it didn’t seem like a big deal.” But when she left Cranbrook this time, she thought: This is a big deal. “Mariah Carey has a song, “Fly Like a Bird,” and that’s what I thought, Oh, I’m flying like a bird. It was like freedom.”

That freedom, she realized, came with a price. She was happy in her marriage but had to spend time away from her husband to pursue her goals. She wanted to make the trip, she had done it many times before. But this time was different. “I was alone, and that was probably the first time I’ve been alone.”

Wilkinson made her twelve hour drive to Vancouver all in one day. She had no job lined up—just her savings, a credit card, and a temporary place to stay.

“I stayed at a friend’s place for about six weeks and walked the pavement looking for an apartment—I told my kids I was a streetwalker,” she says with a laugh.

Soon, she found a two-bedroom apartment on Second Street in North Vancouver and reconnected with another friend she had met years earlier during her community theatre days. Despite a fifteen-year age difference, that friend moved in with her the next day. With a new roommate and apartment, all Wilkinson needed now was a job.

Changing Jobs in Late Life

Nearly a quarter of Canadians have recently changed jobs, according to a 2022 survey—and nine out of ten of those who have changed their jobs are happier after making the switch. These numbers also include semi-retirement, a trend in which retirement-age people transition to working fewer hours, seeking less stressful positions, or changing to more personally fulfilling jobs rather than leaving the workforce entirely. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the number of workers aged seventy-five and older is expected to grow by 96.5 per cent by 2030. During the same period, labour participation in all other age groups is expected to decline.

While some retirees choose to work part-time due to financial need, 60 per cent are taking the leap towards personal fulfillment. Wilkinson’s decision to pursue acting later in life is just one example.

Unlike Wilkinson, Katherine Muir Miller’s late career change came not from pure passion, but from a life-changing head injury in 2015. “I couldn’t work as a nurse anymore,” Miller recalls. “My day-to-day just came to an end and I had to find something to fill my days apart from being in pain.”

After the accident, she picked up a paintbrush—wondering if she could even still paint—and found that it offered a surprising relief from her symptoms. Prior to the injury, Miller had taken painting classes in Ottawa, with a retired art teacher and fell in love with the craft. She began taking courses at the Ottawa School of Art and then applied to as many art shows around Ontario as she could. In 2020, at age fifty-eight, she opened her own art gallery in Perth, Ontario.

Miller describes her work as impressionistic realism, and depicts Canadian landscapes with vibrant colours. She features guest artists across different media that compliment her use and love of colour.

When exploring her craft, Miller attended a workshop by Sara Smeaton, a certified professional co-active coach, who specializes in helping people in midlife thrive professionally and personally.

Smeaton herself made a career change at forty-seven, leaving her job as the managing editor of a non-profit online magazine to pursue her coaching dreams. “It wasn’t a one-time decision; it was just sort of brewing,” Smeaton says. She’d always felt too young and inexperienced, but then started asking herself, If not now, when?

Smeaton stresses that switching career paths late in life doesn’t have to feel like jumping off a cliff, and that there are many alternatives to quitting, such as side hustles or training in one’s free time. “It takes time to get to that spot where you’re doing something full-time,” she says. “Big life changes don’t have to be done in an all-or-nothing way—that often means getting creative and brainstorming ways to get there that are realistic and sustainable.”

The eighty-kilometre drive to Perth proved too long for Miller, who resided in Ottawa, so she closed her gallery in February 2024. However, she hasn’t stopped creating art—she’s simply being more realistic about her capacity.

Miller also didn’t like the business side of running the gallery. She had little time to paint, and the driving was getting to be too much for her, as she had a stroke the year before. Now, she works and sells art out of her home studio and through her online store. Her art will also be displayed in other galleries. Miller will conduct her business like this for now, she says, but is open to the possibility of having another gallery in the future should a space become available closer to her home.

While big life decisions don’t always work out the way people first picture them, Smeaton reminds them that there is never only one way to find fulfillment.

“Disappointment and frustration are natural parts of opening yourself to trying new things,” she said. “When my clients feel this way, we work with the emotions and process them so they can keep moving forward in a way that is true to themselves and what they want most.”

Bucking Expectations

After arriving in Vancouver in 2017 and finding somewhere to live, Wilkinson still needed a job. She had another friend who knew someone working on The Good Doctor, a medical drama about a young autistic surgeon who is recruited to a prestigious hospital. The show was looking for someone who understood sterile technique—a principle that reduces the risk of germs transmitting to patients during surgery—to play the role of a scrub nurse.

Wilkinson knew her way around operating rooms from her decades of work in hospitals. She submitted her résumé and, mere weeks after arriving in Vancouver, was invited to a trial episode. The directors liked her, and she was called back a second time. “The third time I went in, they switched me to the anaesthesiologist, and every time after that, they called me for that role,” she recalls. “I felt very comfortable being the anaesthesiologist. When I sit on set I feel like I really am a doctor. I just feel comfortable—I lose myself in the moment.”

“You’re still you. Why should novelty and new experiences be limited to the first half of life? That’s so silly.”

Wilkinson has now played the anaesthesiologist in episodes spanning across six seasons of the show. One of her favourite moments was when she interacted with actor Freddie Highmore, who plays the show’s main character, Shaun Murphy. In one scene, Highmore’s Shaun explained that he didn’t think his girlfriend should shower with him in the morning, and all the characters in the operating room took a vote on it. Wilkinson barely stifles her laughter as she recounts how her character said firmly, “I vote for in.”

People from her hometown expected her to take a more traditional route and transition into extended care or consulting later in her career. “They thought that’s what retired people in nursing do. But I’ve been there, and I wanted to do something different, something fun and exciting.”

Smeaton teaches a workshop about the list of “shoulds” that middle-aged people are generally expected to do, whether they want to or not. “If I let them, they would spend the whole hour just writing their ‘shoulds’ down,” she says. “We could just spend our whole lives meeting expectations until we die, and it breaks my heart.”

This is why she finds Wilkinson’s story so inspiring. “We internalize these beliefs about aging, and about who we have to be, how we have to look, and what we have to do,” says Smeaton. “Wilkinson’s story is not so much about career change, it’s about bucking expectations.”

One societal belief about aging that Smeaton thinks society has internalized is the idea that there’s a finish line at forty. “I’ve heard so many people say, ‘Before I turn forty, I want to do these twenty things.’ But what do you think’s going to happen on the day you turn forty—you’ll turn into a pumpkin?” she says with a laugh. “You’re still you. Why should novelty and new experiences be limited to the first half of life? That’s so silly.”

Despite society’s assumptions about aging, older people may actually be better equipped to make big life changes. According to Theresa Pauly, an assistant professor at Simon Fraser University and the Canada Research Chair in Social Relationships, Health, and Aging, research shows that older adults report having high levels of well-being despite any cognitive, physical, or social declines they may face. This is called the well-being paradox. “We’re still trying to understand why,” Pauly says, “but overall, older adults report to be pretty satisfied . . . and that’s just fascinating. They face so many adversities, and somehow, they’re able to keep up their well-being. How do they do that? And what can we learn from that for our own lives?”

Blazing a New Path

Wilkinson says she didn’t mean to buck expectations or become a trailblazer; she was simply living by the words her son, Kevin, always said to her. He told her, “‘Just say yes, and we’ll figure it out,’ and that’s been my go-to thing since—say yes, figure it out later.”

During a visit to Wyoming to see Kevin a few years ago, Wilkinson was offered a role as an anaesthesiologist on the TV series Superman & Lois. She’d have to be on set the following week. Even though she would have to fly back to Canada and then make an hour-long commute to Richmond from her home in North Vancouver, she said yes. This is the same can-do attitude she’s brought to her acting career from the beginning. “The only time I had any doubts was if I would go a few weeks without being called, and I’m sure all actors do that,” she says. “I never worried whether I would make it or not, I just took it day by day, episode by episode, and if they called me, I got so excited.”

Wilkinson spent years as one of the few female anaesthesiologists on The Good Doctor and was part of the cast when they finished the series’ seventh and final season. She has also appeared in other shows, such as Superman & Lois and a few other smaller productions.

Now, at seventy-eight years old, Wilkinson is taking acting classes, polishing up her résumé, and on the lookout for her next adventure. “People have to look inside themselves,” Wilkinson says. “Are you okay to stay in the rut you’re in? Is it comfortable for you, or do you want something more adventuresome?”

“I wanted some adventure.”