Could Human Echolocation Redefine What Our Hearing Can Do?

BY LIVIA DYRING

ART BY JOSHUA BEN JOSEPH

———————————————————–

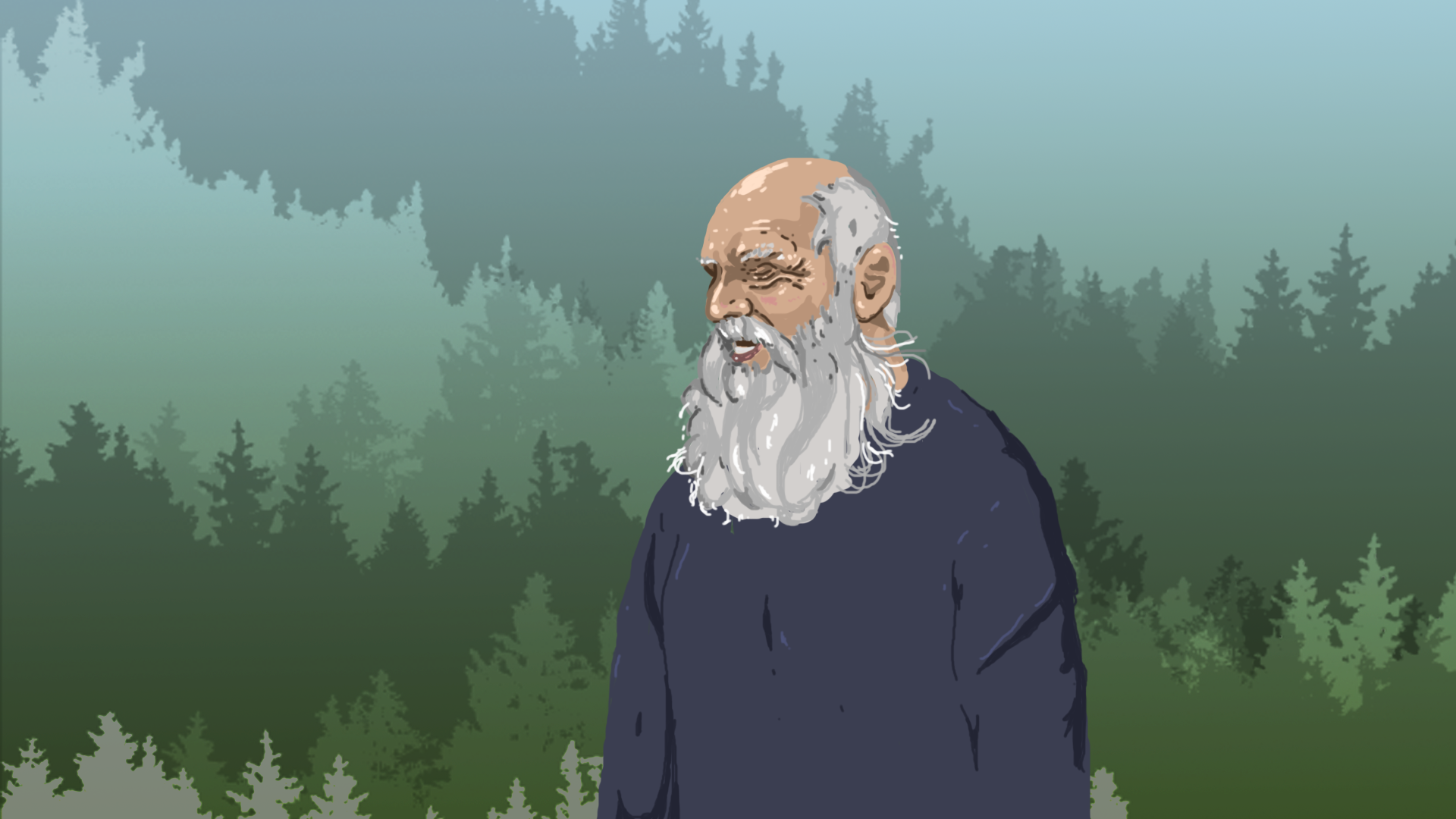

It’s early in the morning in Brofjorden, a fjord about an hour and a half from the Swedish port city of Gothenburg. Leif Sunesson is four or five years old, fishing down by the water. It’s cold, and it sounds that way: the bobbing of the water is slower, particularly sharp. When the sun gradually moves higher up in the sky, shining over everything, the ecosystem of sound engulfing him changes. Every channel of noise travels quicker, and details become harder to catch—become dimmer, less crisp—when the world warms up.

“Why does it sound less now?” Sunesson remembers asking his father, who does not seem to understand the question. “What do you mean, sounds? I can’t hear anything,” his father replies, confused.

Around him, people notice that the boy who became blind within a week or two of his premature birth—placed in an incubator where too high levels of oxygen irreversibly altered his pristine, newborn retinas—has reverted to sound to move through the world.

Sunesson says he remembers walking in the countryside with his bicycle, enjoying the sounds from a set of tin cans attached to the back. He comes to a stop when he hears somebody standing near him. It’s his grandfather. “Is that you, standing there?” Sunesson asks, identifying him by his familiar smell. “What else can you hear, Leif?” his grandfather asks, amazed.

Sunesson can hear the ceiling, to his mother’s great confusion. He can hear the picture hanging on the wall, where the frame starts and ends, and the raised pattern decorating a lampshade, he recalls. When he’s walking down the street, young Sunesson can hear, he says, where the sidewalk ends and becomes a road, four meters away. He does not stop to feel his way over the curb using his feet; he simply lifts his leg and walks on.

When he arrived at Tomteboda’s specialized school for the blind, a now-closed boarding school for blind children in Sweden, Sunesson says he seemed to be the only child who was comfortable running on his own through the gymnasium hall. “It was like seeing.”

Shadows on the Body

Everywhere Sunesson went, the sounds of the surrounding environment offered something tangible by which he could navigate. “When I approached objects, they became like curtains or shapes. I could feel the shadows against my body,” he says. These were not vague but granular and detailed. “When I walked past a fence with three horizontally laid sticks or wires, I could feel where they were, on my arm, my body, my legs,” Sunesson recalls. When he was anticipating an oncoming sidewalk curb on the street, “It was not me approaching it, rather it was approaching me as I was walking—that’s how it felt. It could be a centimetre high or so, it could be heard anyway.”

Sunesson’s curious, uncanny ability to hear his way through the world, allowing him to cycle, run, and walk wherever he wished, is not a mystery nor a superpower, but a formidable echolocation skill he developed as a child. For the many who have never consciously practiced echolocation, the experience may seem unfathomable. Yet, Sunesson and other seasoned echolocators experience the world—not merely by maneuvering around obstacles but by perceiving its shapes, textures, and details, through the often underexplored modality of sound.

Echolocation, sometimes referred to as biological sonar, is typically associated with certain wild animals, such as bats, whales, and dolphins. However, humans can and do routinely echolocate, too. In fact, most practice what’s called “passive” echolocation, where you receive and automatically interpret any noticeable sounds happening around you. According to Thomas Tajo, an expert echolocator and teacher based in Brussels, Belgium, every hearing person—whether they’re sighted or not—uses echolocation to an extent.

Sunesson’s remarkable ability to hear even small temperature changes that affect the nature of sounds is common for skilled echolocators, Tajo says. Temperature changes and sounds they create are “standard physics,” he says, because the density of the air changes when it becomes warmer or cooler. “If you go into a steam room, it’s like you’re echolocating through a sponge or cotton because air is soft, stretched, like a balloon.”

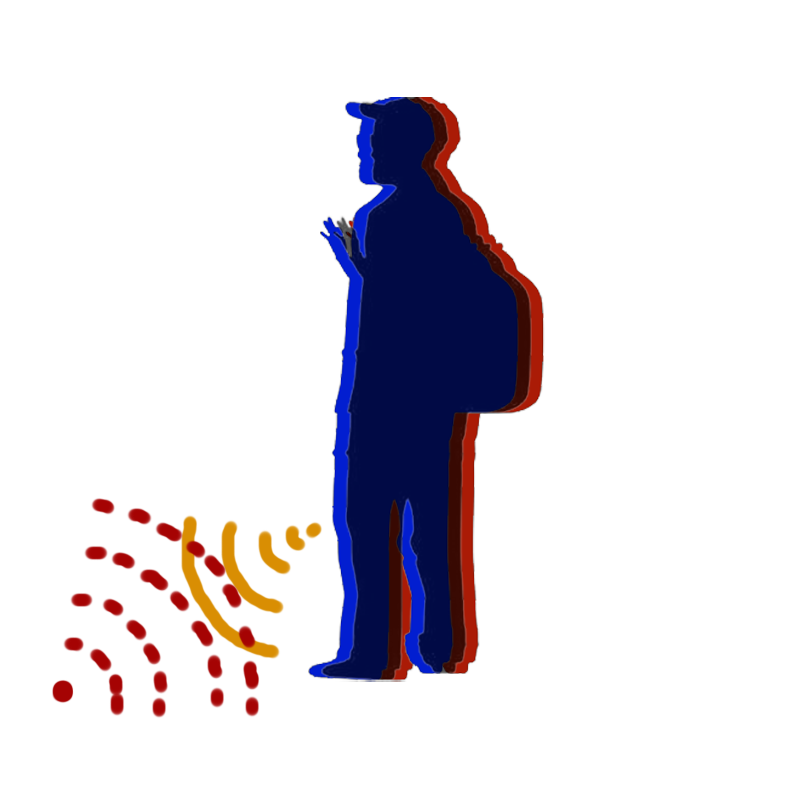

Echolocation can also be performed actively, with the echolocator creating sounds such as clicks done with your mouth or finger snaps that travel out, bounce onto the surfaces of objects, structures and landscapes, and return as an echo. If you listen more closely to the vibrations that create sound, any physical space or object made from atoms—from big, voluminous landscapes of rolling hills, to abstract sculptures displayed in art galleries—they are not mute, but rather keen to talk to you.

Sunesson’s curious, uncanny ability to hear his way through the world, allowing him to cycle, run, and walk wherever he wished, is not a mystery nor a superpower, but a formidable echolocation skill he developed as a child.

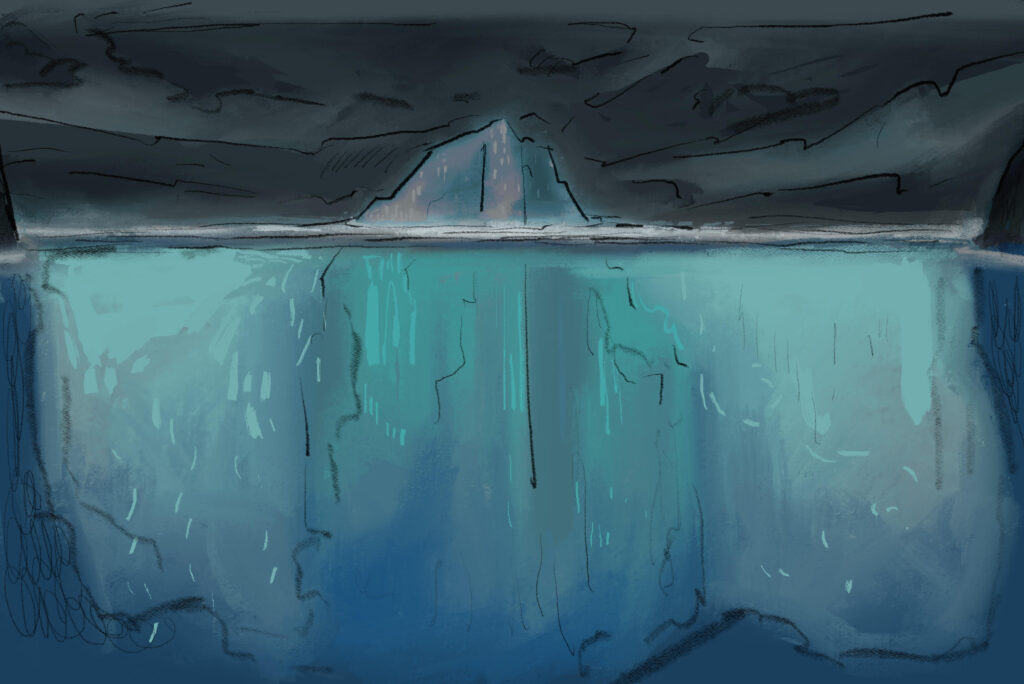

For Tajo, who uses mouth clicks, information about the world resides within the echoes they generate. They are not flat or uniform: the layout and physical properties of the space, from where your click is launched, and its loudness and pitch, all come together in several layers to shape each returning echo’s unique character. From the echoes, Tajo harvests information about not only distance and direction, but also detailed properties of objects and structures like density and dimension. Click into, say, a soft mattress or another person, and the echo will become dull, more absorbed, Tajo says. Atoms packed tightly together in a steel wall, for example, tell a different, firmer tale. But, again, the echoes change dynamically depending on other factors, including distance, he says. The more you approach something, the gap between the click and the echo becomes smaller, and they almost merge into one. “The closer you come, the echo almost disappears, but the further away you go, it sounds very different.”

Ultimately, echolocation helps practitioners form detail-rich images of places, people, and things in their minds. It becomes a type of radar, extending beyond the reach of the long white cane, Tajo says. “You can click anytime, anywhere, and get information about the space around you in all directions, 360 degrees.”

For Tajo, who began teaching himself in his mid-twenties, in Northeast India, echolocation “completely changes” his perception of space. “Without active echolocation, I will have to wait for sounds to come from the environment to tell me about the space,” he says. As a skill, it “changes your perception about yourself, your identity, your conception of blindness. Now, I don’t think of blindness as a disability anymore. Blindness simply means relying on other senses to do your things, to live in the world.”

An Obstacle Course Made of Chairs and a Plastic Brain

When he was four years old, Sunesson began to place chairs on the floor of the small, one-bedroom apartment where he lived. He’d concentrate hard and leap forward, trying to run around them without bumping into them. Behind him, he pulled a small, noisy toy car. Its loud noise created bigger reflections, he says, making it easier for him to distinguish objects from one another. Again and again, he would attempt the homemade obstacle course, the sound of the whizzing car bouncing off the solid chairs. “I did that for perhaps two years,” he recalls, “two hours a day, so I could hear.”

Sunesson began training his own hearing, he says, after overhearing his grandmother complain about how “terrible” it was to take care of a blind child. “Children become very aware, quickly, of what they have to do to please your mother and everyone else around you. So I tried to see, which I of course couldn’t,” he says. “The best way for me was to hear as well as I could and not bump into things.”

“It was a survival strategy that I had,” Sunesson continues. “I was very keen to be good at it, too. Every day when I bumped into things, I had to walk over and feel them and learn those new sounds.”

Sunesson says he might have used mouth clicks in the beginning, but he eventually discovered he did not need them: the shadows, the gentle pressure, he felt were so pronounced he could get by without the clicks.

A blind echolocator’s way of moving through space is difficult for sighted people to even begin to comprehend. Most have never experienced the “shadows” against our bodies that Sunesson describes when we close our eyes and listen to sounds. But once he began practicing echolocation—ever since he began listening, with intent, to the world—Sunesson’s brain began to change.

About a decade and a half ago, Melvyn Goodale, a now-retired neuroscientist at Western University in London, Ontario, and two postdoctoral colleagues undertook the world’s first brain imaging study investigating human echolocation. “It was a complete accident, really,” says Goodale, whose scientific background is entirely in vision. He received an email, out of the blue, from an eye doctor who had arranged for somebody from California to talk to kids who were about to have their eyes removed after being diagnosed with eye cancer or who were going blind for another reason. “He used a white cane, like a lot of blind people, but he was much more confident moving around the city, going off by himself on the bus. And, of course, he made these clicking noises to help him echolocate. I took a look at him online, you know on YouTube and so on, and I was just amazed. In fact, I scarcely believed it.”

Together with two then-postdoctoral neuroscience researchers, Lore Thaler and Steve Arnott, Goodale invited the man the eye doctor had spoken about, Daniel Kish, and another longtime expert echolocator, Brian Bushway, to take part in the study, with the aim of investigating what an echolocating brain looks like. In the lab, they deployed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a tool that can “see” through bone and into the real-time action of living, working brains. When Kish and Bushway listened to echoes, their cortices—located at the very back of the brain and used to process vision rather than sound in people who are sighted—lit up on the laboratory’s computer screen, tissue lighting up as it was being activated by the blood flowing towards it. Goodale and his team confirmed that in the two echolocators, the visual cortex had been “recruited” to turn instead to sound as an input, as the source of information by which it could make sense of space. “We thought something would happen,” says Goodale, “but we were pretty amazed at how clear the evidence was.”

Kish and Bushway’s brains had, in other words, repurposed the space like an interior decorator turns an ordinary, expected living room into an art studio, creating another means to understand and navigate spatial surroundings. As a result, what was tentatively described in 1944 as “facial vision” has emerged as one of the best known demonstrations of the phenomenon called neuroplasticity, or the brain’s ability to change: the ingenious way nature adapts when persistently prompted to. More recent research has only doubled down on Goodale’s team’s findings. “The human brain is amazing and can rise to the occasion, as it were,” Goodale says. “We can learn new skills and our brains can capitalize on the fact that we have some territory that has been vacated that can now be put to good use for other things.”

Sunesson was certainly not surprised by this. “I understood that when I was a child,” he says matter-of-factly. “As I had that fervent, mad intention to try to see with my ears, there were a lot of strange images, back in my head, and these shadows against my body, they are pictures,” he says. “I grasped really early that it has to be the visual cortex working.”

Thaler, now a neuroscientist and professor at the University of Durham, England, has continued in the highly niche scientific area of echolocation research and has uncovered more about the way echolocation works. For one, the brain’s attraction towards echoes, specifically, is clear. “In echolocators who are blind, this part of the brain has much stronger response to echoes compared to sounds that do not contain echoes,” she says. “Sounds that do not contain echoes do not seem to interest that part of the brain very much.”

Thaler’s findings also suggest that any benefits from echolocation are not limited to those who become blind shortly after birth or begin echolocating as young children. Adults who have never echolocated before can develop sensitivity to echoes, regardless of how mature or developed their brains are. “The oldest participant we had was seventy-nine years old,” she says, “and they still learned it.”

The study also showed that results come fairly quickly with practice: the visual cortex can begin to respond to echoes in as little as ten weeks. Even typically sighted people without vision loss can become echolocators, says Thaler, who practices echolocation herself by walking around Durham blindfolded, using a long white cane as an additional aid. “This selectivity for echoes is there in anyone who trains and becomes an echolocator,” she says, “whether blind or sighted.”

In Thaler’s view, however, echolocation should not be used as a “standalone tool,” but is rather something that works best synchronized with other mobility means, such as a long cane or a guide dog. Both as a skill and a tool, it seems to challenge the belief that vision loss must equate solely to loss—loss of independence, of capability, of ways to interact and engage with the world. Still, for the average sighted human being, few prospects seem to evoke more damning fear or pity than the idea of living without sight. In a survey published in 2016, over forty per cent of Americans surveyed said blindness was the worst health outcome they could conjure up—worse than losing your memories, your ability to speak, or one of your limbs. Many people, says Tajo, “have this assumption that vision is necessary to do everything, to enjoy life. “They don’t think that other senses would allow you to do that. They fear losing their vision because they think you have lost the sense of life—that to see is to live.”

Find Your Way

There’s a 12,000-foot drop down to the ground, where Cayuga, Ontario’s patchwork of fields spreads out, its summertime greenness brightened by the midday sun. Ben Akuoko and the skydiving instructor step onto the threshold of the airplane door, the engine blaring, and he makes note of the blueness of the sky faintly coming through his retinas. “One, two,” the instructor counts, and promptly pushes the two of them out. Together, they travel down, down, and down, for fifteen or twenty seconds, every neuron firing in his brain, goosebumps blossoming out all over his body.

When the parachute deploys, the freefall transitions into steadier sailing down to where they eventually find solid ground again. It’s the biggest rush of adrenaline he’s ever had, and he’s happy to be alive, pleased to have checked off one more item on his long bucket list—and to have proven people wrong. Skydiving was but one of the many things some believed Ben Akuoko would never do once they learned he would lose his sight.

Akuoko lives and works in the Greater Toronto Area. He comes across as mild-mannered, jovial, and sincere. He sports an athletic build and a broad smile. “What have I not done,” he says, when asked what he gets up to apart from skydiving. Akuoko lives an active life: he’s a hip-hop artist, actor, podcaster, a runner who’s just signed up to do a half-marathon, a homeowner, and a university graduate with a master’s degree in social work. During the day, he works as a specialist for advocacy and education for the CNIB Foundation (previously Canadian National Institute for the Blind), speaking to kindergarten and school classes and answering common questions from kids about how, for example, he completes everyday tasks.

Even from adults, there are plenty of misconceptions about blindness and low vision, he says. Akuoko goes through them one by one, as he’s clearly done many times before: blind people don’t have social lives, don’t date, can’t be employed, look a certain way, are not physically active—or so people say.

Akuoko chuckles at the latter, and says he’s got totally “jacked” friends whose legs are bigger than his head. “There’s a misconception we’re not attractive, good-looking people,” he says, flashing a broad, white grin. “I don’t want to have vanity, but at the same time, sometimes I almost feel like I have too many friends, right?”

People think you can’t play sports or live independently, Akuoko says, but you can. He rides the train home independently after our meeting, as he typically does, proving his point. And echolocation, he’s keen to say, is not necessarily needed.

Most blind people do not echolocate, and when you’re breaking down the stereotypes of blind and low-vision people, “you want the majority of people to know what it’s really like,” he says. “It’s something people are starting to assume that blind people do.”

“Sometimes people watch one thing and they believe, ‘Oh, everybody echolocates.’ It’s important that people have an opportunity to know that, as a person who’s blind or has low vision, I don’t necessarily use echolocation, or I don’t necessarily use a guide dog. There are different ways people get around,” Akuoko says. “It’s a rarity for someone to echolocate.”

Akuoko, thirty-six, was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic eye disease that causes progressive vision loss, when he was two years old. The cells in each retina—the thick, globus-shaped tissue located behind the iris that processes light—had begun to die, first affecting his central vision and night vision, he says. As his vision has gradually become weaker over the years, Akuoko has paved his way using other tools. One of them is the long white cane, helping him move by probing. “You’re feeling the textures with your cane, by the way it’s moving along a carpet or the way it’s moving along a flat surface, or even when it comes to concrete or a sidewalk, and then on top of that, helping with the drop, if you’re stepping off a curb,” he says. “It’s providing that extra information just by having them in your hands.”

Of areas he frequents often, such as the gym in his condo building, Akuoko creates his own mental maps. “You pretty much recreate your steps, right,” he says. “Sometimes, I feel like I can still see as good as I used to. I just know the area and I have it mapped out in my head.”

That feeling is hard for Akuoko to describe, but he compares it to something akin to muscle memory: you don’t have to think about it, you just do it. “It’s a really neat thing that people can use echolocation—I’m intrigued, for sure,” he says when asked if he’s curious about learning echolocation. But he’s not keen to take it up. For one, he fears that clicking while walking down the street may stigmatize blind and low-vision people. “Sometimes people assume when you live with low vision or blindness, the cognitive aspect connected to it—walking down the street, clicking—it’s almost that stigma: ‘Oh, that blind person’s not well,’”

We tend to think of blindness as a blanket term when it’s a hugely personal, individual experience, says Ray Sauboorah, a sighted orientation and mobility specialist who has assisted Akuoko as well as an estimated thousands of others over two decades. He’s coached infants as young as six months old to people who began experiencing sight loss in their nineties. The vast majority were not born blind and have some amount of functional vision, he says. Due to the variety in experiences, every session is client-centred and focused on what the individual person most wants to learn.

Echolocation is part of his teaching, Sauboorah says, but he questions whether it’s suitable for everyone. “Some people are absolutely excellent, and just have a very honed-in sense of echolocation, and ability to use it,” he says. But for certain clients who are grappling with the emotional and psychological aftermath of a drastically different reality after suddenly experiencing low vision, or seniors who have just begun to do so, he doubts whether it’s the best first step. “As you get older, your hearing diminishes. With the senior population, that is maybe not easy to teach, just because of the physical limitations that come with that.”

Some research echoes Sauboorah’s observations. In one study with a small sample size, researchers found a correlation between echolocation performance and age when blindness occurred, suggesting those who become blind earlier in life might have an advantage at developing echolocation to a finer, sharper degree. Differences in deftness at learning echolocation, based on factors such as attention, have also been found in research where the participants were sighted. Regardless of the specific tools people choose to use, Sauboorah says the independence clients gain ultimately leads to positive emotional and psychological benefits.

For Akuoko, overcoming barriers has been about going against the societal messaging that blindness and low vision automatically means “you’re not gonna live a whole life.” With the decline of his eyesight expected, he was taught how to read Braille and use a white cane as a child. There were hurdles to becoming comfortable using even these, more commonly known tools. In Ghana, West Africa, where Akuoko’s parents emigrated from, disability and blindness remains taboo, he says. Ghanaian society and culture don’t have a word for disability, so, “It’s like you’re] abnormal.” Consequently, Akuoko’s parents initially had low expectations for his future. “It’s seen as you’re suffering, or you’re cursed, or we have to heal you to make your life better,” he says. “It’s almost like you have to hide it—you can’t be free with it.”

For a long time, Akuoko used none of the tools available to him to adapt to living with fading vision. “I remember, probably five, six years ago, talking to a friend who lives with low vision and used the cane, tearfully saying to him, ‘I can’t use this cane because people are gonna look at me different’,” he says. “I never had role models who were Black, who were blind, that I could relate to, right? It’s almost like I was figuring out this myself.”

Connecting with others in the blind community helped him start using the white cane, he says. Something else that changed his mind, Akuoko says, was the death of George Floyd. “Just the police brutality—if people think I’m doing something else, or on something else, my life could be at risk, right?” The white cane, he says, is about awareness and his own safety and personal confidence, as much as it is about navigation. It takes away any ambiguity as to how he navigates through space and makes things clear for sighted onlookers: “I’m blind, I live with low vision, I utilize a cane. Come talk to me.”

Today, Akuoko applauds his West African heritage for making him resilient. “My mindset, my mentality—the African mentality—I just want to get from point A to point B, accomplish whatever I need to accomplish, in whatever shape, form, way I need to.” To arrive at this acceptance, he believes that “liberation of the mind is so key—working towards your goals, no matter what barriers are in front of you.”

A Life for the Senses

Sunesson walks down the street in Gothenburg, white cane in hand, tapping gently. He hears— senses—the concrete, the cars, the people who pass him, the shadows gently falling, veil-like, on his body, arms, and legs. It’s misty and cool outside, and in a moment of stillness Sunesson hears, in a flicker of fleeting sound, the curb resting a few metres away. When weather conditions are favourable for echolocation—when sound travels clearly and crisply—he remembers being able to echolocate as well as he once could.

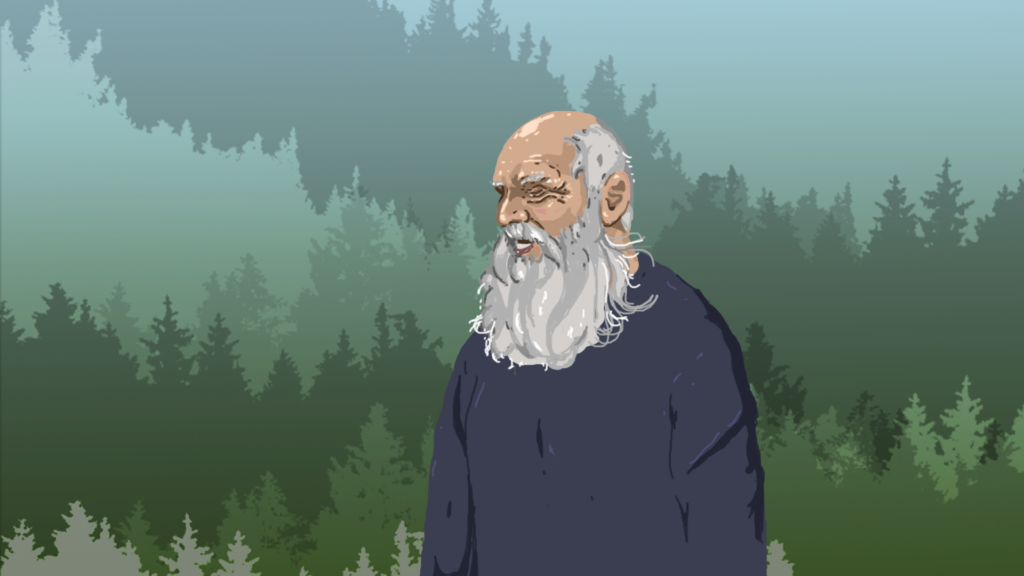

Today, at seventy-four, Sunesson sports a long white beard and travels with a white cane. He can still hear solid walls quite well and routinely walks around spaces he frequents often, holding his hands behind his back to get a renewed picture—a renewed sense of the room—to practice. But while he still uses echolocation, his once highly developed hearing has diminished through aging, and practicing has become a strain. “Now I’m losing my sight—my hearing—I can’t hear the water in the same way,” he says with a hint of sadness, recalling the cold morning he spent fishing down by the water as a child. When Sunesson was running, blind but not aimless, in the gymnasium of Tomteboda school, some staff and other children were in disbelief. “I got comments like, ‘You have to be able to see,’ even from those who were used to blind people. They almost didn’t believe that I didn’t see.”

Over the years, awareness about blindness has improved in Sweden, but not necessarily awareness of echolocation, Sunesson says. “When people see me walk on a street, they still go, ‘Oh my god, can he do that? But there’s a pole over there, and he went right past it, how does he know that? Oh my god, he can do it!’” he exclaims, mimicking the sensationalism, perhaps even the spectacle, many see. He becomes earnest. “If everybody knew how to do this, then you don’t need to have these prejudices that blind people can’t do things.”

Since he taught himself to echolocate as a young child on his own, an echolocation movement, of sorts, has emerged. World Access for the Blind, a California-based organization founded and led by Kish, travels around the world to spread awareness of the technique, calling themselves Modern Scientists, Blind Discoverers, and Challengers of Limits. But despite being widely backed by science, and despite the boons Tajo and Sunesson swear by, echolocation training appears to remain an obscure tool, still not included in most organizations. “Asia has no clue,” says Tajo. “Africa has no clue. South America has no clue. Even in Europe, the majority of people have no idea.”

There are only four or five echolocation teachers in the world, according to Tajo, who uses his own money to travel and teach students. “It’s difficult to get funding because society and traditional blindness-organization funders don’t recognize these methods and don’t fund it. So, even if you want to teach, you really can’t.”

“We have a culture where our parents don’t know about how the senses work, and our teachers don’t know,” Tajo continues. “If your teacher cannot explain to you, your parents cannot explain to you, it becomes very difficult for you to figure it out yourself.”

Echolocation might help these people cope better with vision loss, says Tajo. “If these skills are already developed, losing eyesight completely won’t be such a big trauma because you can still function.” He wishes that every blind person would get the chance to learn and experience echolocation for themselves, and has made it a goal of his to go to a new country every year to introduce the technique. “It takes a while to develop a sharp, consistent click, but it only comes with practice,” he says. “Take your tongue to the gym!”

Sunesson, Kish, and Tajo are but a handful who have learned advanced echolocation entirely on their own. Among every story of people with low vision overcoming barriers, it’s important to note the circumstances that create barriers. Poor accommodations, misconceptions, and stereotypes, as well as a society designed for those who see with vision, become obstacles for many. Psychological distress is relatively common, according to a recent study. Our society has been designed with accessibility largely as an afterthought. It’s a concern, as vision loss has been projected to “surge” by fifty-five per cent by 2050, driven by an increasingly aging population and lifestyle changes.

“When people see me walk on a street, they still go, ‘Oh my god, can he do that? But there’s a pole over there, and he went right past it, how does he know that? Oh my god, he can do it!’”

– Leif Sunesson

Ultimately, though, Tajo suggests that echolocation has “nothing to do with blind people.” Rather, it’s about understanding what our hearing can do, and our underestimation of the senses we as humans, whether sighted, partially sighted, or blind, possess. Unknowingly, Tajo thinks, the world has over several millennia taken the road to where vision is the dominant sense socially, culturally, and biologically—to the detriment of all others. In addition, modern living is rife with sensory disruption that has us straying far away from how we evolved to live on Earth. It’s affected everyone’s innate ability to experience life and the universe, from straining our eyes while looking at screens, denying ourselves a tasty dish because it happens to look not-so-yummy, or never truly experiencing the range and depths of the sounds around us. “We have reduced our own experience to a narrow, one-sense channel,” Tajo says. “It’s reductive, rather than expansive.”

Sunesson once told Sweden’s national broadcaster that echolocation means everything to him. He recalls how his marvelling grandfather asked him to turn his face to the ground and to the sky, and to tell him what he could hear. The world became palpable and tangible, he says.

A place where Tajo goes, where the nature of sound becomes different from the flat lands surrounding Brussels, are mountainous cities in the Himalayas, thousands of meters above sea level. When you are far up, open space sprawling—up and down, north, south, east, and west—you can listen to the far away. Sound travels more quickly, without barriers, through the air, over mountains and down into valleys. “You might not see things that you can hear,” he says, smiling, the experience of these fondly held places emerging in his mind, recalling distant music and people’s voices at parties. “Sounds coming from down the valley when you’re on the mountaintop you’re not able to see.”

“Our senses are not fixed,” Tajo believes. “If you use them, you’re going to develop them. Hearing can do things that you never imagined, and which, scientifically, we never imagined—society never imagined.”