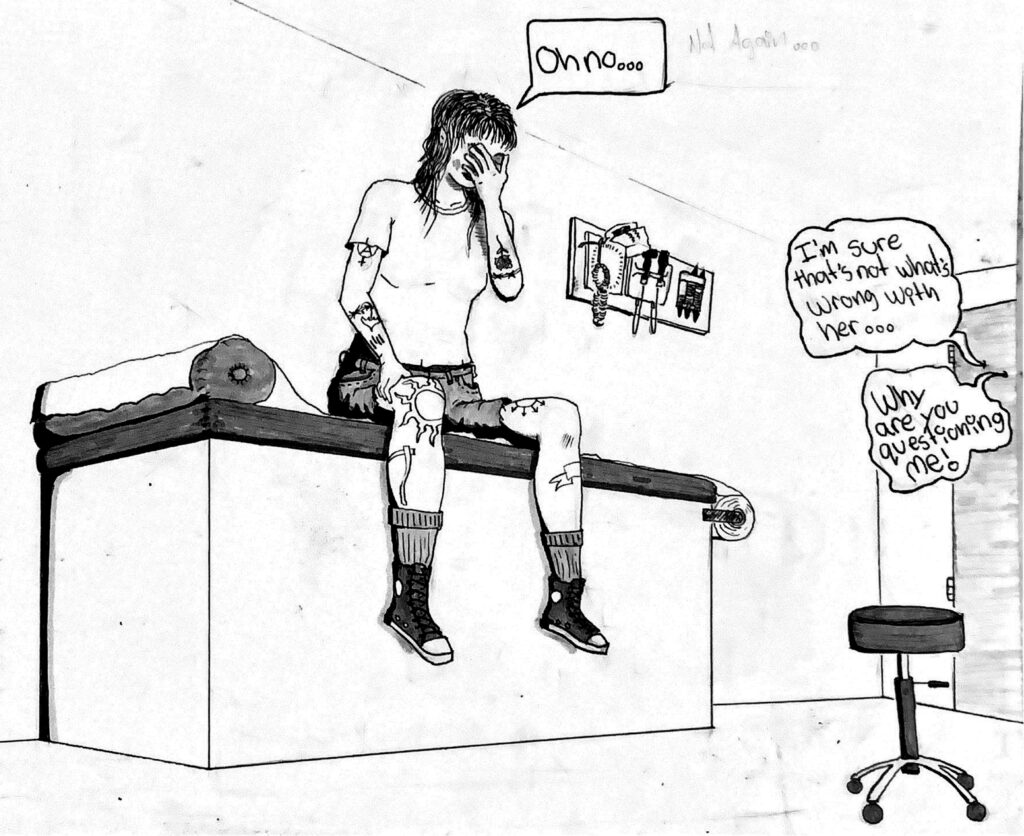

Female athletes experience concussion rates nearly double those of men—this alarming disparity is finally being addressed

BY JENNAH LAY

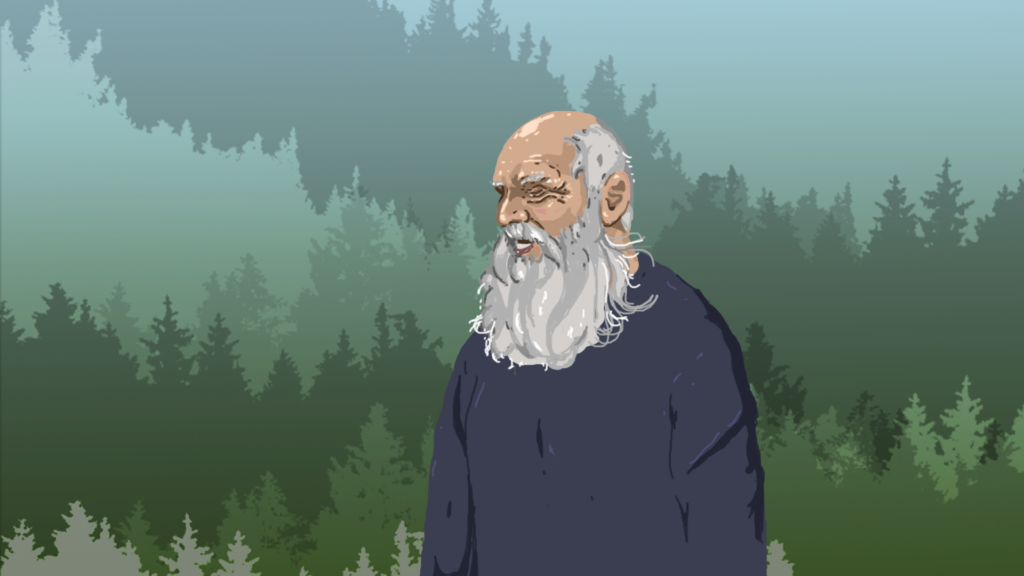

ART BY SAMAN DARA

———————————————————–

On August 15, 2013, while playing for Team Alberta against Team British Columbia during the national championships in Vancouver, Justine Cowitz experienced her first rugby-related concussion. “I don’t think I ever returned to normal,” she says.

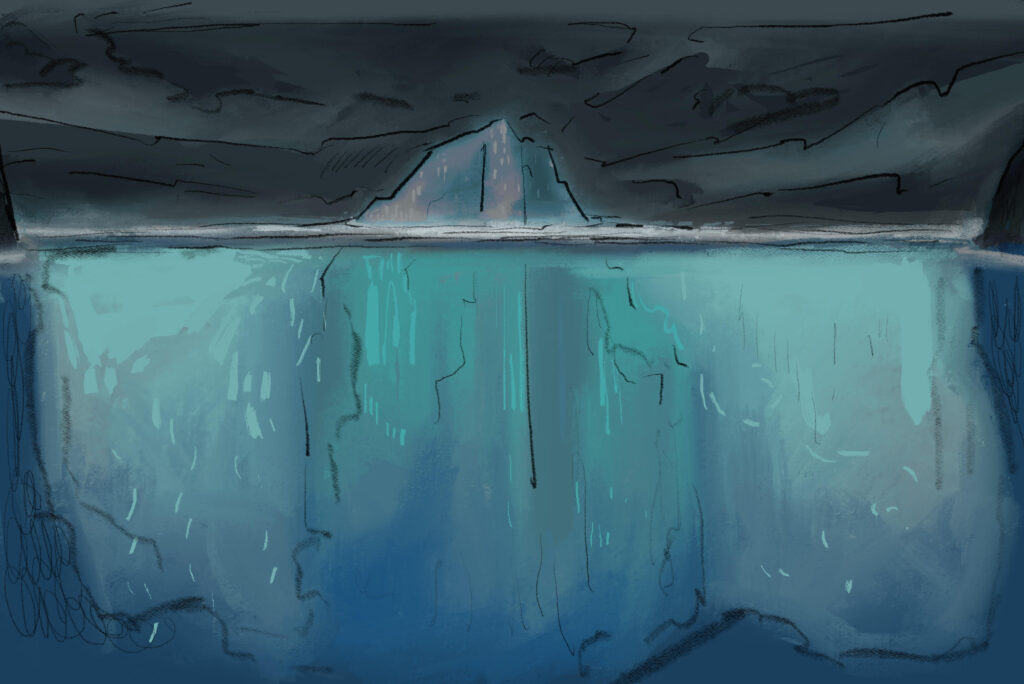

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia defines a concussion as a type of traumatic brain injury (TBI) sustained from a hit to the head or body that causes the brain to move rapidly back and forth. Ten years ago, there was minimal research focused on female athletes who suffered from concussions, despite their high level of participation in sports.

In 2013, medical researchers from West Point, the U.S. military academy, published what it described as a preliminary study to compare rates of injury between male and female intercollegiate rugby players. It found that 8 per cent of men and 15 per cent of women athletes experience concussions. Despite a nearly double injury rate for women, there was a clear gap in the research.

Women who suffer concussions often have greater cognitive decline, poorer reaction times, more frequent headaches, and longer periods of depression compared to men. Research from the University of Birmingham, published in 2023, suggests that “female athletes suffer a higher rate of concussion, which may be accompanied by a wider range of more severe and prolonged symptoms compared to their male counterparts.”

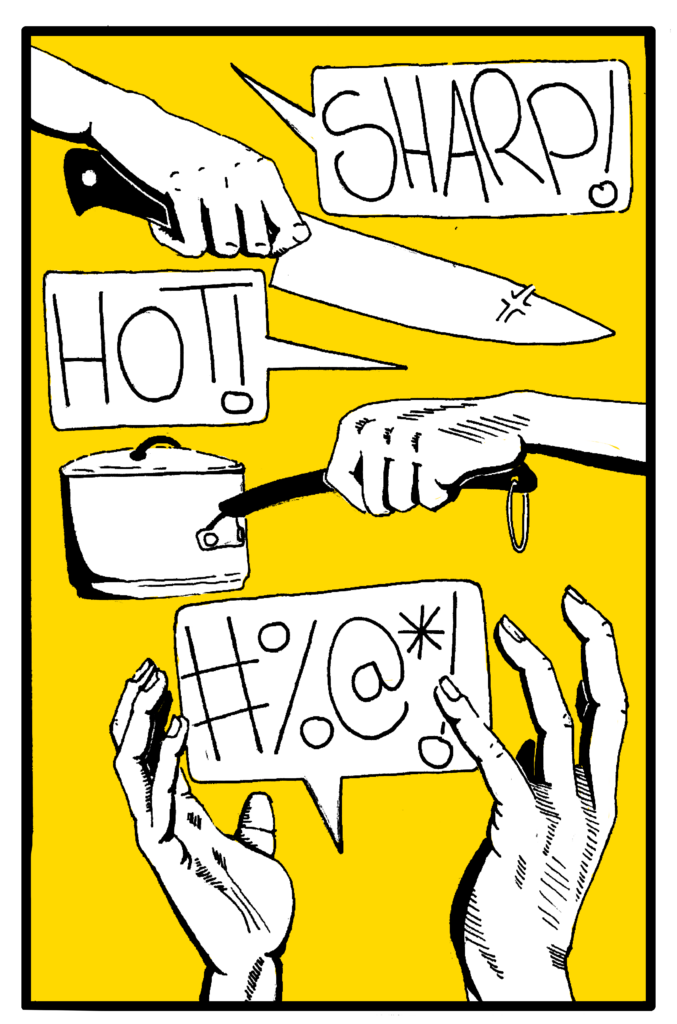

Cowitz says her first concussion slowed her down. “I was in my first year of university,” she says. “I often felt very low energy and had trouble staying focused in classes.” Her second concussion happened in the fall of 2013 during a game at University of Victoria. From the start, strong symptoms appeared: headaches, brain fog, irritability, and light sensitivity. She experienced confusion, the need to be in the dark, and an intense pressure in her head—like an over-inflated balloon ready to pop—and her sense of balance was thrown off. Then feelings of low motivation, gloom, and exhaustion kicked in. “It was just a feeling that I was not fully present,” says Cowitz. “It was an out-of-body experience—just not actually being there.”

“She was not okay, but stepping away from a sport that she loved didn’t seem right either.”

Women’s rugby is an aggressive game and concussions are common. They not only shift memory and the ability to socialize but also have significant impacts on an athlete’s mental health. “I struggled to think of the words to make sentences,” Cowitz says, “and would often drift into space at parties, where I was overstimulated.”

In June 2014, she suffered another concussion during a club team practice in Calgary. “I could easily recognize that I might be concussed after the third one,” she says. “ I asked right away if I could go home, as I had driven myself to practice.”

Cowitz had just made it back to her parent’s house before the headache hit her like a freight train. “I went inside the house and was immediately overwhelmed by my family—their voices alone upset me. I was flooded with emotion and burst out crying, which in turn made the headache worse. I went right to bed and woke up at some point in the middle of the night and started sweating. I was too hot and had too many blankets on. My headache was so debilitating that I couldn’t move to push the blanket off. It even hurt to think of anything other than random chains of numbers, which for some reason was providing me with enough relief to lay there. I remember being afraid and wanting to go to the hospital, but I had no way to alert my family without moving, which I couldn’t do.”

Her return to university that fall was difficult. “I remember going to early morning lectures in packed auditoriums and not remembering my bike ride there and zoning out to the point where I’d almost spill my smoothie. It was enough for my teammates who attended the lecture to notice and ask if I was okay.”

Cowitz couldn’t catch a break. Each of her concussions developed similarly. But the damage was different and worsened each time. She was not okay, but stepping away from a sport that she loved didn’t seem right either. “Most of my second year of university is blurry—I didn’t feel like myself and the lights felt dimmed inside my brain,” she says. “These symptoms didn’t go away as the year went on.”

Eventually, a sports medicine doctor recommended that, since some of her symptoms mimicked Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Cowitz should take a medication used to treat that condition. “It wasn’t perfect,” she says. “I still struggle with focus and concentration but the brain fog lifted. I was able to complete the rest of my degree.”

Throughout her struggles, Cowitz thought it was still too early to step away from the game. She says that whenever she returned, her coaches didn’t appear to be concerned if she had the green light from her physiotherapist and doctor. “I was told I could return to play whenever I felt like it, which is what I did,” says Cowitz. “The result was multiple concussions within a short time frame. Returning to play felt like the priority.”

At the time, Cowitz was among several rookies fighting for positions on the starting line-up for Team Alberta. She remembers feeling replaceable, the coaches only really caring about whether or not she could play. But while their expectations may have contributed to her returning to the game too early after each concussion, the need to be a competitor (a mark of value in rugby) might have been a stronger influence. “There’s this overwhelming feeling that you’re letting your teammates and coach down by prioritizing your well-being.”

Out of Body Experience

An analysis of nine studies and nearly 700,000 people by the American Society of Anesthesiologists, published in 2023, found that besides the more familiar symptoms, “Women are nearly 50 per cent more likely than men to develop depression after suffering a concussion or other traumatic brain injury.” Olivia Sarabura, a University of British Columbia (UBC) rugby player who has also experienced multiple concussions during her rugby career, describes symptoms of a current concussion that are eerily similar to Cowitz’s.

Rugby is an aggressive contact sport, and with that comes an increased risk for concussions. The hits come quickly and are often out of view. Sarabura knows all too well about the impact of concussions. “What was light sensitivity at the start, the next challenge became my balance. As the concussive symptoms progressed, that’s when I started to experience depressive symptoms. It’s also this feeling that I’m not fully present. It’s an out-of-body experience,” Sarabura says. “Everything just sucks right now.”

Dean Murten, UBC’s women’s rugby coach, says that the mental health effects of concussions are probably the worst part for the players. “They cannot play the sport they love,” he says. “Some of the athletes can’t even exercise to fully keep their well-being, and then there is, of course, their education. If you start to struggle in all three areas, it becomes really challenging, and that leads to more mental health issues.”

“For Cowitz, these changes came too late. She found herself torn between the sport and her health.”

But Murten also believes the game’s attitude toward concussions is changing. UBC’s athletics department has measures and protocols in place to detect concussions and keep athletes from returning to the game too early. For example, a large portion of players wear high-tech mouthguards that measure the force of impact on the head and the direction of the hit. “We’re involved in really good things at the moment,” he says. “We do a baseline test at the start of the season, and anyone who then gets a suspected concussion does a baseline test again.” This baseline test looks for concussive symptoms such as reduced concentration and decreased memory.

Once an athlete is diagnosed with a concussion, Murten continues, they are tracked through the different stages of concussion recovery. They cannot progress from any stage until they show none of the symptoms associated with it. The sport’s large governing bodies, such as Rugby Canada and World Rugby, also have specific concussion policies and protocols.

The Ontario-based Blue Card program, launched in 2019, aims to reduce the likelihood of concussions in rugby athletes. If teammates, trainers, or coaches notice that a player is showing concussive signs, they can alert match officials, who then hand that athlete a blue card. That player’s name is then flagged in a database, and they cannot be added to a new game sheet until completing a return-to-play process that includes an assessment by a doctor or nurse practitioner.

For Cowitz, these changes came too late. She found herself torn between the sport and her health. After a fourth concussion, she chose her health. “The pain I experienced was to the point where I knew I had to quit rugby, although it took me another eight or nine months and a bike crash to really quit,” she says. “I’m convinced that I never had enough recovery time between any of the concussions and that the recovery time should have increased after each one.”

Cowitz now spends her time outdoors. In the summertime, she helps to tackle the B.C. wildfire season and in the winter she ski patrols. To this day, Cowitz continues to take medication to manage post-concussion symptoms. “My desire to continue to play this sport definitely dug the hole I am in right now,” she says. “I wish that I could have had the wisdom to quit the sport sooner.”