How stigma and medical bias often result in later autism diagnoses for marginalized genders

BY MADELINE LIAO

ART BY CALLIA SILVERTON

———————————————————–

Twenty-five-year-old Irene Chon sits stiffly in a small, private clinic in December of 2021. The room is small, with only a desk separating her and the clinician, who is about to assess her for autism spectrum disorder. She recalls a series of assessment questions and hand-eye coordination exercises done over five hours. When the clinician pointed out her stiffness, balled fists, and rapid eye movements as subconscious traits connected to autism, she had a moment of clarity. Having these subconscious actions explained back to her helped Chon learn more about her mannerisms and how they relate to autism. Finally, at the end of the assessment, Chon was diagnosed with level-one autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Walking out of the clinic, Chon says she didn’t feel any different than before her diagnosis. She had done her research and had practically come to terms with being autistic without the assessment. But, she says it felt like she “finally understood why.” Receiving this diagnosis was a step in the right direction, as she felt she could move on and better integrate autism into her day-to-day life rather than masking her traits. While it wasn’t a huge awakening, having the diagnosis on paper was a relief. “Now, if people don’t believe me, I could just show it to them.”

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the manual used by Canadian and American professionals for evaluation, level 1 ASD is considered the lowest severity level of autism, with most individuals requiring some external support but not a substantial amount. However, according to a 2022 study from the U21 Autism Research Network—which surveyed over 650 English-speaking autistic adults worldwide—many consider terms referring to levels of function and severity as “harmful and inaccurate.” The study suggests using specific descriptions such as “autistic person with intellectual disability, autistic person with minimal verbal language or autistic person with extreme anxiety and a co-occurring physical condition,” if necessary.

Uneasy Journey

This six-month journey to a diagnosis was not easy, Chon says. She recalls her psychiatrist suggesting that she had borderline personality disorder—which can be categorized as “a pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, and marked impulsivity,” according to the American Psychiatric Association. Chon says she didn’t resonate with this diagnosis and later faced doubts from her psychiatrist when she brought up the possibility of being autistic. She was told that she “couldn’t be autistic” because she was good at doing her makeup, had a nice sense of style and didn’t have model trains in her room, amongst other stereotypes of autistic people.

“I had a moment of just being completely speechless,” Chon says. She recalls experiencing dissociation for a week after this occurrence. “I was numb for a good amount of time. And after I started to come out of it, I realized, ‘Okay, I just need to hunker down, I need to keep calm and not let that hold me back from seeking my answers.’”

The closest adult assessment professional she found in her search was in Southern California, six hours away from her home in the San Francisco Bay Area. Even though she lives in a heavily populated area with multiple esteemed medical institutions, such as Stanford University and the University of California San Francisco, she couldn’t find any clinics nearby that assessed adults. Chon was fortunate in that her wait time was around three months, a considerably shorter time than many clinics with waitlists of months or even years. She was grateful that getting her diagnosis took only six months, compared to the many years that most autism diagnoses take. She credits her expedited process to luck and finding a specialized, private practice.

Masking really comes with a cost. There’s a mental burden, having to mask and camouflage all day

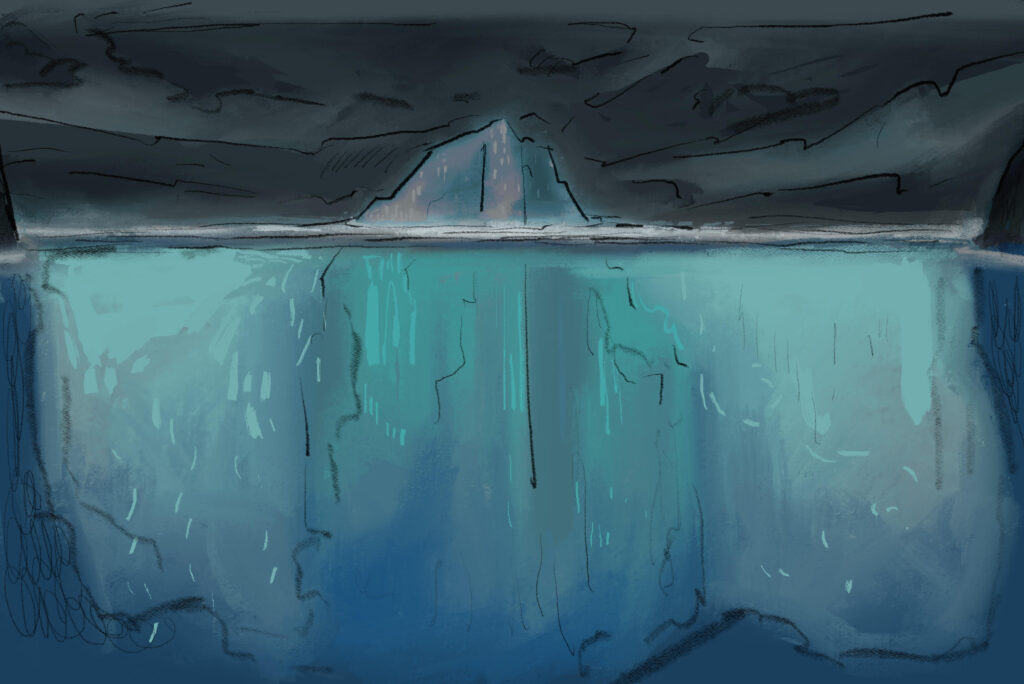

Stigma and lack of professional understanding of autism spectrum symptoms are the main factors as to why many go undiagnosed until adulthood. This situation is especially true for those of marginalized genders, including women and non-binary individuals, who are still widely misunderstood and left out in professional research on the autism spectrum, according to experts. In a 2017 study, data found that women are often diagnosed later in life due to the lack of medical research on the broad spectrum of symptoms and the tendency among women to camouflage their autistic traits to conform to societal norms.

Dori Zener, a registered social worker and a founder of a neurodiversity-affirming mental health clinic in Toronto, says that a negative response to autistic traits causes those of marginalized genders to hide autistic characteristics, resulting in a lack of recognition. This may cause them to appear more socially skilled and less stereotypically autistic, says Zener. “In most realms in public, they tend to appear neurotypical, and then they might come home and have a meltdown or shutdown,” says Zener. “There’s just a gender bias in medical research.”

Undiagnosed Neurodivergent

Chon now runs a YouTube channel and podcast called The Thought Spot, detailing her experiences living with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In one of her videos, she goes through her elementary school report cards and looks at them through a refreshed perspective, now knowing she was an undiagnosed neurodivergent child. She reads how teachers described her behaviour, including how she had trouble focusing on subjects outside her interests and her tendencies to speak bluntly to peers, and elaborates on her difficulties with understanding social cues and interacting with classmates as a child. She says that being the only girl alongside two brothers in her family greatly influenced her growing up, which she understands more now post-diagnosis.

“I was constantly being held to very intense standards, especially physically,” Chon says. She expresses that having to act and look a certain way, such as being dainty and feminine, affected her as a person, especially since these standards were challenging for her to understand, not knowing she was autistic. These expectations also reflect a lack of diagnoses for women and other marginalized genders, as stereotypical autistic traits are based on male-presenting behaviours.

“There is still the perception among some clinicians and practitioners that autism is rare in girls. And so, when they see a girl, they don’t even think about autism as a possibility,” says Christine Wu Nordahl, a professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute. Wu Nordahl says that, oftentimes, due to societal norms and expectations, those who are not cisgender male-presenting are accustomed to masking or concealing their autistic traits. “Masking really comes with a cost. There’s a mental burden, having to mask and camouflage all day,” says Wu Nordahl. Zener echoes this sentiment, saying that when an autistic individual masks for a prolonged period of time, this instinctive stress can lead to a mental health break. “They’re acting like they’re not themselves, so, not really being authentic to who they are,” she says.

For Chon, masking throughout her life prevented her from realizing that she might be autistic until her twenties. She says part of it is being a woman and having that pressure to maintain relationships and display expected social skills in a neurotypical society. If I could have all these friends, talk to people, and maintain eye contact; if I could have these deep, flourishing relationships with people, there’s no way I could be autistic, she would say to herself. “I think autism presents itself differently once you’re an adult compared to childhood because you have your masking skills and scripting skills; you have all of these coping mechanisms that might be so ingrained in you that you may not be aware that you’re doing them yet.” For instance, she recalls that even during her assessment, she was unintentionally sitting on her hands to avoid moving them. Chon hopes that by sharing her experience online, it will benefit others going through similar situations. “If I could try to make that a more streamlined experience for someone else out there, I want to be able to put that information out to be accessible.”

Oh, This Is Probably Me

Similar forms of accessible information were helpful for Kip Chow, a graduate of the University of British Columbia (UBC) who also studied American Sign Language and Deaf studies at Vancouver Community College. Finding information and connecting with disability support groups online helped them take that step toward finding a diagnosis. They recall reading posts from other autistic people and thinking, Oh, this is probably me. So, in June 2020, after consulting with their family doctor, Chow got a call from a clinic covered by public health care in Vancouver to take the place of someone else who had cancelled. They were originally on a waitlist with a one- to two-year wait time.

The month after, Chow and their mother went in for evaluation. While the relationship between them and their parents “could have been better,” growing up, their mother was willing to go in for the evaluation and was understanding of the situation. Part of the evaluation consisted of a two-hour interview between Chow’s mother and the clinician, and then the other part was around a half hour of Chow interacting with the clinician.

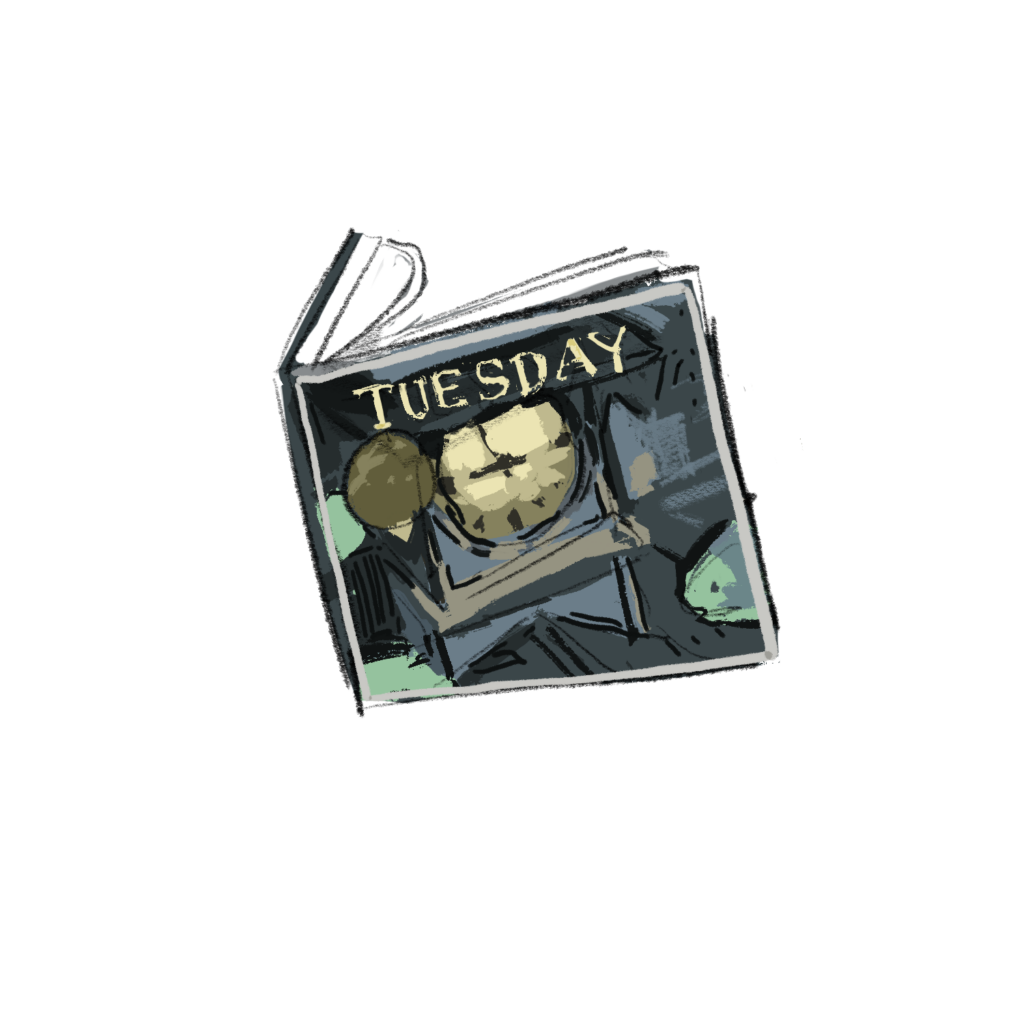

Chow laughs as they search Wikipedia for the picture book used in their assessment. Tuesday by David Wiesner is a primarily textless picture book with illustrations of various frogs. Chow was asked to describe this book in their own words, as well as the seemingly mundane process of brushing their teeth. They also recall being asked questions about their friendships. At the end of this assessment, they left with a diagnosis of “high-functioning autism.”

Chow’s main reason for getting a diagnosis was academic accommodation. They were finishing their bachelor of arts at UBC and were facing heavy autistic burnout. According to a study from the journal Autism in Adulthood, autistic burnout differs from regular burnout because it is a result of masking autistic traits and lack of access to support and understanding of one’s needs. As noted by an article in The New York Times, “Autistic traits can amplify the conditions that lead to burnout, and burnout can cause these traits to worsen.”

At the time, Chow was experiencing problems with auditory processing in longer video lectures, so the diagnosis allowed them to request that professors either include closed captions or provide transcripts of course content. They didn’t necessarily need medical validation, but it was nice to know that the research they had previously done was correct. Chow felt proud about being correct about their suspicions. When they first went into a consultation with their family doctor in 2019, they brought in a list of autistic traits they identified with, in case the doctor was skeptical.

Neurodiversity was never a possibility in their household, especially growing up in a Chinese family, and this caused them to be viewed as weird without specific reasoning

Accessibility is a common reason for autistic adults to seek a formal diagnosis, says Marty Lampkin, a registered clinical social worker and professor in the social service work program at George Brown College. “In the way our [societal] system is structured here, without that diagnosis, you don’t get access to forms of additional support,” she says, “So there may be people who feel like they require this or they have to justify it.” Lampkin says that every individual may have a different reason for seeking a diagnosis, whether for personal liberation and understanding or external validation. She also says that some individuals may not want to pursue a diagnosis because of the stigma associated with ASD. “It’s about opening up and normalizing those discussions for people and not assuming that everybody’s going to have the same response to a clinical diagnosis.”

Growing up, Chow viewed autism as a predominantly white and male condition and didn’t encounter many autistic people who were Chinese, let alone non-binary. Most of the autistic children in their schools were boys, which subconsciously skewed their perception of the spectrum. They also say that due to this lack of representation in their surroundings, it didn’t occur to Chow that they could be autistic. “You just don’t consider what you don’t see.”

Lampkin says that intersectionality in services is essential to combat a lack of representation. She says when professionals only specialize in one sector, such as disability or LGBTQ2S+ support, those who belong to multiple marginalized communities may not receive the care they need in all factors of life. “You’re looking at multiple layers of marginalization and those things manifest in different ways,” says Lampkin. “I think that’s what happens when folks either don’t get diagnosed for a very long time because they’re experiencing that racial stigma and discrimination first. Or folks just don’t want to seek out that support, because it’s not a safe place for them, and they see no representation of themselves within that.”

Lampkin stresses the significance of medical professionals being well-versed in various communities as best they can to ensure that people of multiple identities can be fully seen in society. “I may be working from that disability lens. But how do we also connect with folks who provide services to the queer community?”

Looking back, Chow realizes they exhibited specific autistic traits as a child. They explain how they learned to read at two years old, which is earlier than most neurotypical children. According to an article from the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, hyperlexia—the development of accelerated reading and word recognition skills—is a relatively common trait in autistic children. Chow mentions a time in elementary school when they were assigned to mentor a student in a younger grade, only to be shocked that the student was still learning to read. This trait, among others, such as having hyper-focused interests—they mention Pokémon—and conducting intensive research on a subject, such as video games, that they had no intention of ever playing, are characteristics they didn’t grasp were autistic traits until later. Chow says it was because of the lack of acknowledgement and representation growing up that they couldn’t understand these traits. Neurodiversity was never a possibility in their household, especially growing up in a Chinese family, and this caused them to be viewed as weird without specific reasoning. But now, they understand that this perception has a deeper meaning.

This stigmatized view of ASD is not uncommon in Asian culture. An article from the Asian American Journalists Association’s Voices program states that families in Asian communities often hide disabilities, including ASD, because of a fear of scrutiny. “Revealing a mental disorder could jeopardize not only the child’s future but also the family’s reputation,” the article notes. Additionally, a study from the International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, in which 30 Chinese-American immigrant parents with autistic children found that some of these Chinese families with autistic children lacked an understanding of ASD as a whole, viewing it as a temporary issue that needed to be solved. “Families expressed feelings of haste and a strong need to ensure that their child would catch up to the progress of other peers,” the study states. “Several Chinese families in this study seemed to identify the loss of face as being a primary drive for self-driven social isolation.”

But now, even when reflecting on their childhood and identifying those potential autistic traits, Chow says they don’t know if an early diagnosis would have benefitted them. They say that because of how education systems and medical institutions treat autistic children, they are hesitant to believe their needs would have been met even if they were diagnosed earlier. “Being diagnosed as a child means that you have the potential to be exposed to so much institutional harm,” they say. “You can’t win either way unless we address the root of the issue, which is ableism and not having our needs met.”

Neurodivergent individuals have worthy voices and perspectives—even if society currently does not yet fully understand them

Like Chon with her YouTube channel, Chow has also been outspoken about their diagnosis and the need for more accessible services for autistic adults. They even hosted a TEDx Talk at Simon Fraser University detailing why many adults go undiagnosed. Chow said in this talk that they were lucky to have had access to the resources to “figure out that [their] brain wasn’t broken.”

A Literally Painful Physical Experience

While the moment of diagnosis itself didn’t necessarily change Chon’s life, she says she feels life has improved following diagnosis and understanding her autistic traits. Whereas she struggled heavily with anxiety and depression before diagnosis, Chon says, now she can’t remember the last time she felt depressed or anxious like before. Without the diagnosis, she says, “I feel like I wouldn’t have been able to get to this point of living a peaceful, non-painful life. And it’s funny I say that because I literally mean painful as a physical experience—pre-diagnosis, life was so painful.” Pre-diagnosis, she would experience physical anxiety through migraines and neck pain but now she can better manage her stressors in order not to experience this pain as much.

Natalie Engelbrecht, the co-founder of Embrace Autism, a platform to distribute research and experience-based information on autism based in Oakville, Ontario, mentions the benefits of diagnosis in a panel hosted by Autism BC. In the panel, she said that having a further understanding of one’s self through an autism diagnosis can be beneficial for mental health. “It [diagnosis] can save your life, and it certainly did with me,” she says. Engelbrecht, who was diagnosed as autistic at age 46, says that a diagnosis helped her navigate anxiety and depression in a healthier way, similar to Chon.

A 2019 study indicates that many adults diagnosed with ASD view their diagnosis as having a positive impact on their mental and physical health. “Receiving a diagnosis was seen as a positive step and allowed for a reconfiguration of self and an appreciation of individual needs,” the study says. However, even given the positive impact that diagnosis can have on some individuals, the neurotypical standards ingrained in society still result in scarce support for autistic adults. “More support is needed,” the study says, “to allow individuals receiving a late diagnosis to question their taken-for-granted assumptions and behaviours and to rethink their biography and self-concept.”

Chon is proud of her neurodiversity and doesn’t see it as something to hide. She thinks that neurodivergent individuals have worthy voices and perspectives—even if society currently does not yet fully understand them. She hopes that as more people are diagnosed and community awareness of autism progresses, society can be more supportive of neurodivergent individuals by educating themselves. Smiling, she says, “I like to think of neurodivergent people as just colourful people that are not coloured within the lines.”