Digital fashion is stitched together with hypes and hopes, but is it just a naked promise?

BY MADDY MAHONEY

ART BY CHIARA GRECO

———————————————————–

I didn’t expect to find God in the metaverse. I really didn’t expect to find him taking in a fashion show. But he appeared unto me on the third day of Metaverse Fashion Week, sporting a red and gold toga with his signature crown of thorns—and, in a less canonical move, a pair of pixelated sunglasses. Much of Decentraland, the video-game-esque website where Metaverse Fashion Week is taking place, is still unfamiliar to me. Perhaps that’s why I stand next to Jesus Christ and not the man in a bucket hat and giant marijuana-leaf wings, or the woman in skimpy black lingerie with a plague doctor mask. At least I understand His symbolism.

We stand in silence and look at the runway, a purple figure-eight with large flowers (or are they onions?) on either side. Nearby, a cross between a dinosaur and a robot wrangles a group of avatars into facing the same direction at the same time for a photo op. I notice my new friend’s name floating above his head—in this world, He goes by “Skazi.” In a few minutes, models will walk the runway in faded, multicolour tracksuits and black puffer jackets, occasionally performing jerky dance moves or floating momentarily off the ground. But before that begins, He disappears. God has officially abandoned this place.

Metaverse Fashion Week was the first of its kind, and it was entirely dedicated to digital fashion, an industry growing at the intersection of traditional fashion and virtual realities. For four days in March 2022, brands with household name recognition like Dolce and Gabbana, Puma, and Forever21 joined digital-native fashion designers for a celebration of virtual clothing that included runways, panels, and even afterparties—all online in Decentraland. All of the garments on the runway were NFTs (non-fungible tokens). Some of them had real-world counterparts. Most didn’t.

It may seem niche, but in the months since Metaverse Fashion Week the metaverse has only continued to amass attention—and investment—from the fashion world. At New York Fashion week in September 2022, Puma premiered its very own metaverse platform called Black Station, joining the growing list of major brands—including Balenciaga, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Nike—to invest heavily in a metaverse presence. According to Reuters, investment management company Morgan Stanley has estimated that by 2030 the digital fashion industry could account for $50 billion in sales. And new facets are being added all the time. Most recently, modelling agency Photogenics has announced that it’s creating metaverse replicas of real life models that can be hired out for online fashion shows. Metaverse Fashion Week claims to have been the first of its kind—but it seems that it will not be the last.

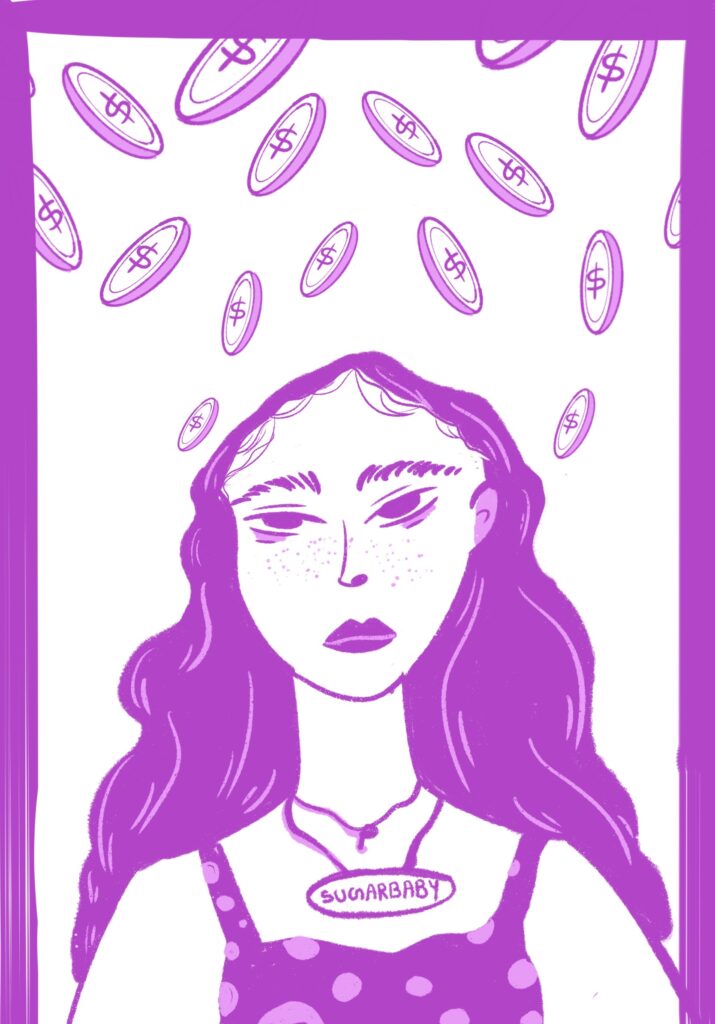

For most of us, scenes from the metaverse fashion world feel like a crypto-acid-trip. But disciples of the industry hail digital garments as a balm for fashion’s most pressing issues. It will be sustainable, they say, it will be inclusive, it will be fantasy freed from real-world limits. Like the Great and Powerful Oz, proponents of this world make fantastic, appealing promises. Skeptics might be forgiven for wondering if there’s something else behind a nearby curtain.

All Dressed Up, Nowhere to Go

“Everyone’s a VIP in the metaverse,” reads the Metaverse Fashion Week website. “Experience fashion without limits.” It’s commonplace for metaverse spaces to claim to be a horse-of-a-different-colour, if you will, when it comes to status and prestige. Countless articles and marketing copy laud the metaverse as a “democratizing” space. Unlike the “real” world, as long as you have a computer and internet connection, you’re just like everyone else. It’s a big claim—especially when applied to the traditionally status-obsessed world of fashion.

I didn’t exactly feel this egalitarian fantasy upon arrival, but it was partially my own fault. When I was setting up my avatar in Decentraland, I let the platform “randomize” my look. It was just a quick reconnaissance mission, I didn’t want to waste time curating my avatar just then. Cut to two days into fashion week, and I couldn’t for the life of me figure out how to stop existing as a mustachioed man in a red t-shirt, yellow swim trunks, and flip flops. Even at an event where people are sporting names like “Freelonmusk” this felt embarrassing.

I did eventually figure out how to change my outfit, but then I started to notice something else. Now that I had gone through the limited options Decentraland offers to users who haven’t bought any custom garments or “skins,” I started to recognize these default items on other people. As for anyone wearing something unique—I knew on sight that they had invested more time and money into the metaverse than I had.

The idea of a metaverse entered the popular imagination last year by way of Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook rebrand, but he didn’t coin the term. The first use of the word to refer to the internet’s ability to create virtual-reality spaces was in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 science fiction novel, Snow Crash. In this sense, the term metaverse can be applied to any virtual-reality space—if you have a virtual body, and are in a virtual world, it’s a metaverse. And dressing your virtual self has been a part of life in the metaverse since video games like The Sims began popping up in the early 2000s.

It was, however, a video-game business model that invited fashion with a capital F into virtual worlds. In 2009, Riot Games launched the game League of Legends and pioneered the free-to-play business model. Rather than making people pay for the game itself, they made money by selling players a variety of small, in-game items. There was one caveat: according to video-game historian Geoffrey Lachapelle, it’s frowned upon to sell items in a game that offer a competitive edge. Instead, players buy “skins” that are purely cosmetic, which has created a culture where it’s normal to spend real money on digital-only clothes. Fast forward 10 years, and this opened the door for an explosion of collaborations between video games and major fashion houses. Louis Vuitton, Gucci, and Valentino are among the many brands whose digital garments are available for purchase inside video games, which serve as commercial hubs where brands can access a large customer base. “The point of all of these different branded properties together,” says Felan Parker, a scholar of media industries from the University of Toronto, “it’s to sell them more effectively.”

Developing alongside this market are the exact kind of social stratifications that you would expect to find IRL. When someone wears expensive, brand-name garments in real life, they communicate wealth to on-lookers. Digital garments work just the same. But, according to Parker, it would be too simple to write off these spaces as purely commercial or purely prestige-oriented. Like a mall, many video games are bounded, proprietary spaces, and one of the fundamental reasons they exist is to make you buy stuff. But people also live their lives in the hallways of these worlds. “Digital culture is a space that is real for us, right? It is meaningful for us, even though it is co-opted by advertising and commercialism,” says Parker. We know that IRL clothes mean more than just how much they cost; we use them to express ourselves, to communicate our individuality. The full meaning of how we wear and interact with digital clothing may not be clear yet, but conspicuous consumption has already become an entrenched use of the technology. If this is what’s at the heart of the metaverse, then its democratic ambitions may not be what they seem. And virtual extravagance can have real life consequences.

Green Dresses and Greenhouse Gases

In 2019, The Fabricant, a digital-only fashion house, made history by selling the first virtual garment using blockchain technology. It was called Iridescence, and its look was true to its name—a shimmering, silver catsuit with a translucent, plastic dress draped overtop. Though The Fabricant didn’t describe it this way at the time, its dress, which sold for almost $10,000, was essentially bought and sold as an NFT. That caught the world’s attention. A dress you can’t wear? At that price?

It also caught the attention of Angella Mackey, a designer and researcher who has been working at the intersection of fashion and technology for over a decade. She took notice of the advent of digital clothing, but also knew that fashion’s flirtations with new technology rarely worked out. To find out whether wearing digital clothing could be as meaningful as wearing physical clothing, Mackey decided to take on an experiment. She would wear greenscreens for an entire year—well, garments that acted as green screens. It began with a single green dress, and expanded into a whole wardrobe of green items. The colour allowed her to project moving images and patterns onto them, in a higher-tech version of a Snapchat filter. This type of digital fashion is often referred to as “hybrid” because it combines digital and physical elements into one garment. “It was very kooky to some people,” she says. “Eventually, the novelty wore off for people I was seeing every day but there was always this kind of like check like, ‘Oh, are you wearing green today?’”

“‘Jack the Rapper’ is an inflated leopard print snowsuit-ish garment… with ‘I <3 NFTs’ stitched across it.”

The green-dress experiment was born out of skepticism about whether this new trend had any longevity. And Mackey was not the only person willing to see what came of treating digital fashion as something with real, tangible potential. In 2021, as Mackey was finishing up her thesis, Balenciaga released its Fall collection in an online platform designed specifically for the occasion. As more brands dove into virtual spaces, Mackey was discovering that virtual clothing could indeed mean something to the people who wore it. The filters she projected onto her garments, filters that only appeared on her phone or computer, coloured her memories of that year. She recalls frequently choosing to filter her clothing in a particular set of shimmering, iridescent colours in the same way that one might return often to a favourite T-shirt.

But she was also left with one planet-sized question. “There is this narrative that doing things digitally for fashion will be better for sustainability purposes. I don’t have the information to answer yes or no to that. I just know it’s incredibly complicated and it needs to be questioned.” One of the major selling points of digital fashion is that it could curb the industry’s penchant for creating waste. It goes like this: if people satisfy their fashion whims digitally, they could be more thoughtful about their IRL purchases. In turn, this would lessen consumer participation in fast-fashion-style shopping and decrease the fabric and water waste associated with the mass production of cheap clothes. Mackey suspects this argument is simplistic, and she’s not alone. “According to my best knowledge, what is not really being researched or looked at is, what is the impact of these blockchains,” says Dirk de Waal, a sustainable fashion scholar from Toronto Metropolitan University. While the environmental footprint of blockchain technology writ large is being investigated, de Waal says no one is looking critically at the cost of digital fashion ventures.

It might be less visible than a pile of discarded fabric, but running virtual worlds and selling virtual garments has an environmental footprint. While I’m in Decentraland, my computer is running, and the computers of the other attendees are running, and all the computers needed to build and maintain this world and present these fashion shows are running. Not to mention all the computers supporting the use of cryptocurrency to buy and sell the NFTs. This all has an energy cost, and that energy, unless it’s from a truly sustainable source, emits a ton of greenhouse gases. How much? Well, that’s the problem—no one really knows.

NFTs (New Fashion Trends)

Designer Christian Guernelli says when it comes to digital fashion, most people gravitate towards the outlandish. One of his designs, entitled “Jack the Rapper,” is an inflated leopard print snowsuit-ish garment, complete with neon accents and a full-face covering that has “I <3 NFT” stitched across it. If, as Guernelli says, people buying NFTs want something they would never wear in the real world, then this certainly fits the bill.

Guernelli comes from an Italian fashion family, but when he started showing his fashion NFTs to his parents, they were surprised to learn they were digital garments rather than photos of IRL items. “They’re old school,” he says. They were also surprised that some of Guernelli’s NFTs sold for upwards of $3,000. “I was surprised also in the beginning, honestly. I thought, what do people do with this? After that I started to understand that they are collectors. People collect everything, and there are people that collect digital art.”

NFT refers to a unique digital asset. If an asset, web-based or not, is fungible, it means it can be easily replaced by another identical item. If I had a looney, and you had a looney, and we swapped, we’d both still have a dollar. Non-fungible, like the “N” and “F” of “NFT,” means that the asset is unique and cannot meaningfully be swapped with another item. If I had a dress that was one-of-a-kind, and you had a different one-of-a-kind dress, swapping them would fundamentally change what we each have.

“Picture this: you’re wearing a navy-blue gown… You’re on your way to a football game. In the metaverse.”

Garments that can only be worn in a video game or platform like Decentraland might not seem worthwhile to everyone, but at least they can be worn, albeit in a digital setting. The kind of NFTs that Guernelli makes can sometimes be edited onto a picture of you, but outside of that cannot be worn—the graphic quality is too high for any currently existing metaverse platform. Guernelli is right that, at this point, these expensive NFTs are generally bought either by collectors with money to burn or by people who view them as an investment that might accrue value. And Guernelli has already seen some of his NFTs resell at a substantial profit—one of his designs, which originally sold for $3,000, has more than quadrupled in price, selling for $13,000.

Maybe one day, if the technology catches up, one could wear these NFTs in a metaverse of some kind. But it’s an investment in a hypothetical future, and a risky one at that. “Would you pay a lot of money for a promise to get a dress in five years? And who knows what is valuable in five years, right? Or what is in fashion in five years,” says Alfred Lehar, a professor who studies cryptocurrencies at the University of Calgary. “So maybe you’ll get your dress in five years, but maybe it’s totally out of fashion and you would not be happy with it.”

Adding to the potential of a future fashion faux-pas are the substantial costs involved: $13,000 is not an investment many can afford to take lightly. Plus, fashion is an inherently social activity; the aesthetic value comes largely from the fact that other people see you wearing it. An investment in a digital garment isn’t only a bet on that item, it’s a bet on the creation of a metaverse where other people want to live. Lehar doesn’t see the promise of great returns, saying, “Unless you want to do it for fun I would be concerned about these investments.”

As for Guernelli, despite his proficiency in virtual design, he retains some of his parents’ old-school values. When asked what he would wear in the metaverse, it’s clear that he’d rather stick with what he has than go off chasing the outlandish. “Probably, based on my personality, I will wear the black T-shirt.”

The Fantasy, the Sales Pitch, and the Amoeba

Picture this: you’re wearing a navy-blue gown made of a material that appears to be a cross between latex and leather. It’s stiff—the dramatic shoulder and A-line skirt hold their form—but it billows perfectly around your figure. It’s patterned with bright golden stars, connected delicately together into a myriad of constellations. You’re accessorizing with a bold, yellow-beaded necklace—like pearls of a different colour—and a hat that looks as if a butterfly the size of one hundred butterflies has perched gently atop your head. You’re on your way to a football game. In the metaverse.

This is Morchen Liu’s idea of the future. The present, well, he could take it or leave it—he wasn’t thrilled by the pixel-y graphics in Decentraland. But when I talk with him about the future of digital fashion, it’s clear that he’s optimistic. Why shouldn’t he be? After dropping out of a “very conservative” school in China, he’s selling his NFT designs for thousands of dollars. He even sold one to an organization called Red DAO, a prominent—and well-funded—collector of fashion NFTs.

One of the founding members of Red DAO is Dani Loftus, who preaches the gospel of digital fashion all over the internet. Within these assurances about the future, one in particular stands out—both Loftus and Liu claim that digital fashion will be inclusive of all body sizes. It’s the internet, after all, and virtual clothing can be stretched out to fit any size of avatar or edited perfectly onto any person’s photo. Loftus takes it one step further. You—yes, you!—she says, could even be an amoeba if the mood strikes. This claim, that digital fashion is a shortcut to body inclusivity, is not novel. It can be found across the virtual fashion universe. When we’re all dressing digitally, the physical limitations and expectations that our bodies are subject to IRL will fall away, regardless of your size.

It’s an appealing idea (except, perhaps, the amoeba part) but digital fashion seems as invested in thin bodies as real-world fashion has always been. Over the course of Metaverse Fashion week, only one body that walked the runway in Decentraland was bigger than the skinny default avatar. As for NFTs, the trend these days is to display them as short animations where the clothing is draped over a ghost of sorts; there’s no model, but the clothing is fitted onto and moves with an invisible body. And that body is always sample size. Technology wise, yes, it could be any size you wanted it to be, but it’s clear that digital fashion wants one size only. According to Kimberly Wahl, a feminist fashion scholar, fashion has struggled to be more inclusive because the industry is fundamentally profit-driven. Brands and designers believe that if they make size inclusivity a part of their mandate they will suffer financial consequences—so they abandon the initiative altogether. Instead, mainstream brands tend to stick to the current business model which promotes thin bodies and conventional attractiveness. From their perspective, this marketing tactic has always worked, so why change it?

When Liu and I finish our interview, he asks me for something. “Do you mind if I take a photo so I can post it on my story?” He leans back, poses, and takes a screenshot of us together on Zoom. When I see it on his Instagram later, I realize that he’s framed our interview as a sort of ad for himself: an NFT designer taking interviews from journalists around the world. I remember him telling me that digital fashion is about fantasy—but it’s always about selling, too.

The Future (?)

There are a few shopping districts in Decentraland, but the atmosphere is the same in each—desolate, disorienting, bizarre. I spend time wandering around the mannequins. Some are sporting wedding gowns made from soccer balls, others robot heads that oddly resemble record players, a rare analogue reference. I hardly ever see anyone else, and if I do, we almost never talk. I recall a comment someone made at one of the runways: “The future is definitely now!” I wonder about this future and whether these barren malls could really become a fashion utopia, free from waste, sizing, and any limits besides those of our own imaginations.

A lot of the technology behind fashion NFTs and events like Metaverse Fashion Week actually has innovative, maybe even revolutionary, potential. The program that Guernelli and Liu use to design their NFTs—a software called CLO3D—was originally created to reduce waste in the process of making physical garments and if widely applied, could do so. Traditionally, garments are designed through trial and error with real fabric, and going through multiple versions of a garment means that a lot of fabric, a huge source of water waste, just gets thrown away. Designing garments in a hyper-realistic virtual space allows for experimentation without the physical debris. If you try something and don’t like the way it looks, you can toss it out without scrapping perfectly good fabric. These types of programs could also be used for made-to-order business models. Rather than making 50 garments, which may or may not sell, brands could make a physical garment only when someone actually buys it.

“The real fantasy is the idea that new technology can be a panacea for social change.”

Digital programs like this might also help designers make garments for bigger bodies. They could, virtually, put the garments on avatars made with larger measurements. From there, they could see if the garments pull or snag anywhere, and then make adjustments. Physically trying on an item of clothing might still have to be the final step, but this kind of process could help designers truly engage with clothing structured for people who often get left out.

And who knows, maybe digital fashion does become the next big industry. Weirder things have happened. If it did, selling garments as NFTs puts designers in direct contact with buyers. A one-to-one transaction like this could mean more money for designers. Plus, they could make a percentage of the sales if the NFT sold again later, as long as they enter a smart contract with the buyer to ensure they get a cut. This could be a big financial bonus for small or independent ventures, giving them more room to innovate.

But it’s naive to think that just because a new technology could do something, that it will do something. In theory this utopia could exist, but it certainly isn’t a given. It might be sustainable, but we don’t know much about what the environmental cost might be. At this point, it’s more of a buzzword than a well-founded commitment. As far as sizing goes, we have all the tools on earth to make physical clothes that fit everyone who lives here. The fact that brands often do not do so is simply a matter of priority, and a virtual setting alone won’t change that. And fantasy is all well and good, but in a branded, commercial space, not all fantasies are created equal. It’s fundamentally misleading to suggest that a space will be inclusive when the price tag is in the thousands.

The real fantasy is the idea that new technology can be a panacea for social change. Anything we create is, well, created by us, and it turns out the old adage applies just as well in digital worlds as it does IRL—wherever you go, there you are.

Exiting the Metaverse

It’s late in the evening on the first day of Metaverse Fashion Week. Before the runways, before the after-parties, before God. I’ve still got my mustache and I’m struggling to figure out how the controls work. The sky is dark—Decentraland runs on Coordinated Universal Time, the same time-zone as London, England, five hours later than Toronto. Unexpectedly, someone replies to one of the messages I keep sending into the ether (“hey y’all”). A bald man dressed in all black with orange, reflective sunglasses is standing beside me. He’s surprised when I tell him it’s my first time here. We chat. He’s an architect. He’s interested in NFTs. Suddenly, he tells me to follow him.

He walks ahead of me. I have to run, periodically letting him get further ahead, because I haven’t figured out how to walk yet. We wind through the streets of the Luxury Fashion District before stopping in front of a statue of an avatar, a sort of weirdly de-sexed garden cherub. The revolving sign beneath it says, “DROP ME MONEY LIKE IT’S HOT!” The man tells me to throw money at it until it changes, and as he does, other avatars materialize in front of me and start doing just that. He assures me this doesn’t involve real money; one of the few actions Decentraland avatars can perform is throwing fake bills. I join in. After a few minutes of this, the statue begins lifting into the air and the message changes to “KEEP GOING! KEEP GOING!” More people appear, more money gets thrown.

Eventually, it starts jumping up and down. “CONGRATS! YOU DID IT.” I look around—but everything is the same.