My sisters were both medicated for anxiety, but I held out. Why couldn’t I join them?

BY MAYA ABRAMSON

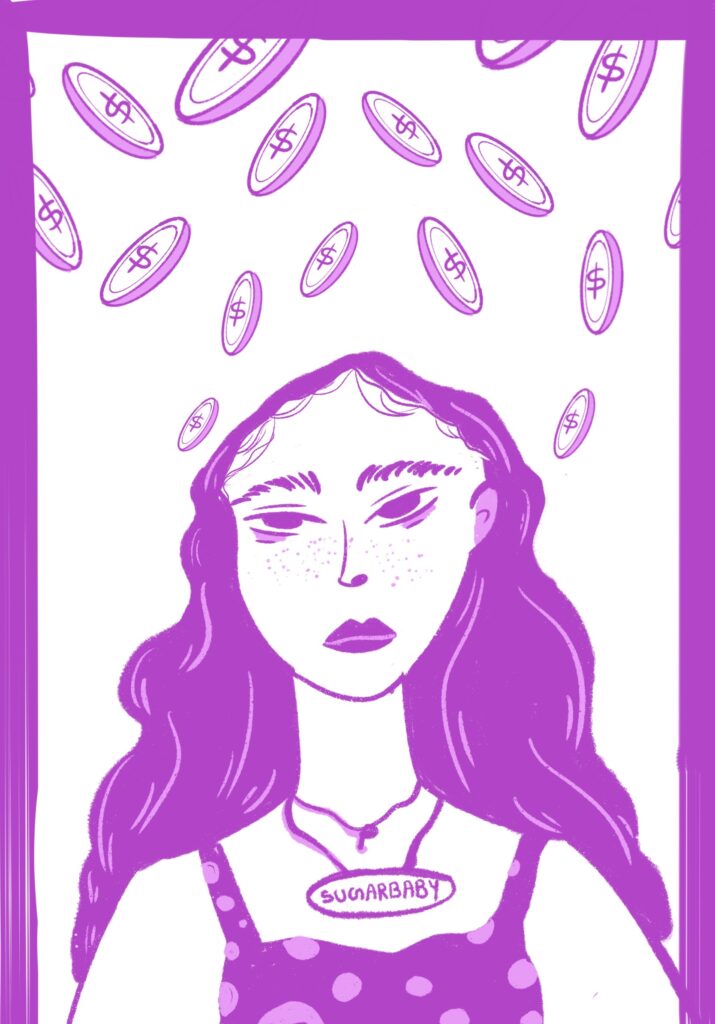

ART BY ERIN SASS

———————————————————–

One early afternoon in January, I was washing my hands when I noticed my orange pill bottle on the bathroom counter. It contained almost a hundred tablets of Escitalopram, commonly known as Cipralex or Lexapro. Suddenly, I couldn’t remember if I’d taken one that morning. Following my doctor’s directions, I’d been taking one each morning since she prescribed the medication a few weeks back. Yet, I couldn’t recall taking one that day. As I tried and failed to conjure an image of myself taking the pill, that stupid orange bottle stared back at me.

Did I take one? Probably. But I can’t remember.

What if I didn’t? Probably nothing bad will happen to me.

But what if it does? And why can I not remember?!

I can feel my fast pulse quicken even more, and then comes the familiar tingling sensation in my palms as they start to sweat profusely. I try practicing some of the techniques I know—deep slow breathing, in and out.

I probably didn’t forget. Most likely, I didn’t forget.

And even if I did, nothing bad will happen.

And really, I probably didn’t forget.

My brain constantly plays tricks on me like this, convincing me I’ve done something terribly wrong when the actual consequences are minor. But, even knowing this about myself, the panic does not fully subside. Even after I’ve slowed my breathing, I can’t help but ruminate on my potential mistake for the rest of the day.

“My brain constantly plays tricks on me like this.”

As is common for me, I struggle to be present in conversations with my family because I’m consumed with cycles of worried thought. And yet, I spent years resisting medication. Now, it seems almost funny. How did I possibly convince myself that my anxiety could be handled without it? If this is how I habitually react to minor issues, with worry taking over my whole day, how am I supposed to function in the world? The truth is, I spent several years convincing myself that I was not deserving of medication for my anxiety.

Popular discourse around mental health suggests we should treat mental illness the same as physical illness, and yet equating the two can be difficult. While progress has been made in reducing the stigma around mental health issues, it is not gone for good. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that stigma has decreased significantly for depression since 2006; yet it remains stagnant for many other disorders. In terms of schizophrenia and alcohol dependence, the study found an increase in social stigma, which can have its own consequences, even for people who understand mental health well.

I have two sisters, Talia and Sarena, and all three of us now take medication for anxiety. Each of us should probably have tried medication earlier than we did, but there were various obstacles in the way. My sisters and I are well-versed in issues of mental health and stigma—they both held leadership positions on a mental health advocacy group we volunteered for at our high school. Yet, even for people in the know, there can still be barriers to medication. For some, especially youth, it may be the disapproval of parents or family members. Others may have fears about putting a new substance in their body. Many, like me, struggle to see themselves as needing or deserving of medication, despite accepting it as the right path for others.

Why Is Mental Health Different?

I spent years telling people, “Sure, I have a lot of anxiety, but I don’t have an anxiety disorder.” I finally saw a psychologist when I was 20, and it took her about 15 minutes to determine that my symptoms were in line with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). My therapist explained that GAD is characterized by persistent and irrational worry, where seemingly everyday concerns can cause distress. Statistics Canada has estimated that about five per cent of Canadians will experience GAD in their lifetime. This new label was helpful in validating my symptoms, but also opened the door to imposter syndrome and self-doubt. In my eyes, the fact that many struggled with mental health problems far worse than mine disqualified me from medication. I found talk therapy helpful, but not life changing. Many of the techniques used in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) mirrored the way I naturally processed and analyzed situations, so it was not a novel approach for alleviating my anxiety. I always knew medication was an option, but I fixated on the fact that I had survived so far without it, deciding this meant I was unworthy.

It can be difficult to decide when to turn to medication for mental health, especially because there are many ways to treat mental illnesses. Dr. David Gratzer, an attending psychiatrist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, says that many people can treat anxiety disorders with additional exercise, a reduction in caffeine intake, or talk therapy strategies, like CBT. Yet, even when other treatment options are not sufficient, many patients still hesitate to try medication.

“I had to admit that medication was the next step.”

Gratzer explains that many are resistant to medication because of a natural human tendency to minimize ailments, mental or physical, as well as particular stigmas around mental health issues. Patients are often uncomfortable with their own mental illnesses and resist treatment. “Mental health problems are particularly unnerving for us,” he says. “If I have a bad hip, it’s just my hip. If I have a mental health problem, this is an attack on who I am.”

This idea lies at the heart of my personal struggle with medication. So much is wrapped up in how we self-identify, and I wanted to be the kind of person that was fine on my own, without the help of a chemical boost. Eventually, the turning point came when I found myself withdrawing more and more, consumed with my own cyclical thoughts. I spent the beginning of winter break after my first semester of grad school riddled with anxiety, even though I had few responsibilities or rational stressors. Eventually, I had to come to terms with the fact that I was doing everything right but my anxiety was more present than ever. Despite my efforts to sleep well, exercise often, and practice the techniques I learned in therapy, it was not enough. I had to admit that medication was the next step. So, at 22 years old, I finally decided to give it a try.

Sarena’s Path to Medication

Sarena, my younger sister, wakes up in the morning in Grade 9 with a feeling in her body that you might get right before you head to the airport. Her stomach is immediately in knots, and her anxiety level is so high that her limbs feel strange. Slowly she gets ready for school: she eats a banana muffin for breakfast, brushes her teeth, gets dressed, and packs a pizza bagel for lunch. However, when it comes time to leave, she can’t force herself out the door. She stands in the hallway, crying, as my mother tries to coax her to go. She catastrophizes her coming bus and subway rides, ruminating over the worst irrational outcomes until she becomes too anxious and overwhelmed to leave on her own. She is petrified of getting to school late, but the longer she waits at the door the more likely that outcome becomes. After much yelling and crying, my parents either finally push her out the door on her own, or give in and offer her a lift to school. This daily ritual is a cause of great concern and frustration for my parents, who cannot understand why it is so difficult for her to face transit and school each morning.

This was five years ago, and Sarena is now 19. Despite the toll this experience took on the household, my parents did not seek a formal diagnosis or medication for Sarena. They took her to see a social worker, where she engaged in talk therapy and developed strategies to cope with anxiety. Medication was never mentioned as an option. My parents knew of other families who found medication beneficial for their children, but they were resistant to try it for their own daughter.

Fears around medication for youth experiencing mental illness are common. Dr. Ashley Miller, a child psychiatrist at the British Columbia Children’s Hospital, says parents may have numerous fears about medication. Many worry their child will experience adverse side effects, become dependent on the medication, or that their personalities will fundamentally shift. “Parents are always very concerned about changing their child,” she says.

In Sarena’s case, she eventually settled into high school and became more comfortable in her morning routine. Still, throughout her high school experience and into the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, her anxiety persisted. She recalls the shame of having to cancel plans with friends in the summer after Grade 11 because leaving the house and being far from a bathroom made her too anxious. When she was accepted to Queen’s University in Grade 12, she began to worry about her ability to thrive away from home. “I don’t think that I will do well, going away to university in my current state,” she recalls thinking. She finally called the doctor to discuss her options, and she started taking medication about a year and a half ago, just before her eighteenth birthday.

The Family That Stays Together, Medicates Together

It may seem strange that all three children in my family have anxiety disorders that benefit from medication. However, there is evidence that conditions like GAD can be inherited, and my family history is full of mental health problems. My mother’s anxiety presents itself similarly to Sarena’s, but she historically sought treatment for stomach problems rather than looking at the anxiety that may be at the root of those issues. Earlier this year, with the encouragement of all three of her children, my mother decided medication was worth a try.

My maternal grandmother also suffers from anxiety. She tried medication once, many years ago, but did not like the experience and decided to stop taking it. Then, to the surprise of our whole family, she started a new medication at 88 years old. She says this medication has increased her appetite, but she has not noticed a major change in her overall mood. My paternal grandfather also has a history of anxiety and has had a similarly difficult relationship with medication. Although the stereotype of anxiety being more common in Jewish families like my own has not been proven with research, studies on twins show that anxiety can be passed down genetically, as I suspect has happened in my case. One 2017 study from Germany estimates the heritability of GAD at around 30 per cent.

“The nausea, the sweating, and the stomach turmoil…they can get in the way of life.”

Research has yet to prove exactly which genes can contribute to inherited anxiety or depression. What is known, however, are the social ways in which attitudes toward mental health can be passed down from one generation to another. Our outlook on how mental health issues should be treated, including our views on medication, can come from our culture in general and directly from our parents. Miller notes that parental disapproval can be a barrier to medication, even when patients are old enough to make their own health decisions. “It’s very hard to take a medication as a young person if you know, explicitly or implicitly, that your family doesn’t think it’s a good idea for you,” she says. In my own family, my grandma’s skeptical attitude toward medication trickled down through my mother to my generation. My mom avoided medication for decades, following in her own mother’s footsteps. My sisters and I inevitably internalized the idea that medication is not necessary, even if you live with intense anxiety.

What Is It, How Does It Work?

Every day, I take 10 milligrams of a drug called Escitalopram, a type of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI). It increases levels of the serotonin, a neurotransmitter, in the brain. SSRIs stop serotonin from reabsorbing into neurons, meaning more is available to transmit messages from one neuron to another. The drug is ‘selective’ because it only targets serotonin. Escitalopram is most commonly used to treat Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and GAD, but it can also be effective in treating conditions like Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Most SSRIs take a while to kick in, up to eight weeks on the long end. For me, the change was so gradual that I can only really notice it in hindsight. Ten milligrams per day is the most common dosage, but doctors can increase it to twenty milligrams if necessary. My sister Talia, for example, increased her dosage in consultation with her doctor around the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. SSRIs are generally the first choice of medication for mental disorders because they tend to be well tolerated, and they have less potentially-harmful side effects than other types of antidepressants. There is still a long list of potential side effects that can occur with this medication, but my sisters and I have only experienced mild problems. Talia recalls feeling slightly intoxicated for the first week after increasing her dosage. Another rather strange potential reaction is frequent yawning—I noticed this in myself over the past few months, but didn’t see the link until I saw it on a list of possible side effects. Sarena has not noticed any adverse side effects at all.

Talia’s Path to Medication

All three of us can recall experiences of anxiety as children, even though they were never labeled that way at the time. My older sister Talia remembers crying to a camp counsellor because she was convinced the raw cookie dough she ate with cabin mates had given her salmonella poisoning and she was going to die. Sarena recalls stomach aches before every single swim lesson or dance class. She frequently called our mother in tears to pick her up from school because she felt feverish, far more often than was conceivable for her to have a natural fever. I remember lying awake at night on vacation with a horrible feeling in the pit of my stomach, as I ruminated over the possibility of the plane crashing on the trip home.

These instances are a reminder that anxiety often presents with physical symptoms. The nausea, the sweating, and the stomach turmoil are all bodily responses to anxiety, and they can get in the way of life. Sarena was encouraged to try medication, in part, because Talia shared her own positive experiences after she decided to start medication at age 23. Talia, who is now 26, explained that medication made her physical symptoms from anxiety more manageable, helping her calm the all-consuming brain-body feedback loop of disaster.

“Taking medication for your brain comes up against our ideas of personhood.”

For Talia, resistance to medication was not about self-stigma like it was for me. Nor was it related to the reluctance of family members, like it was for Sarena. Talia was open to the idea of medication but had always dealt with medical anxieties. The idea of taking a new unknown substance was terrifying, so she wanted to be certain that it was necessary before she started. The turning point came when she felt herself burdening those around her. “When I got anxious, my instinct was to reach out to my friends or family and call them and dump all my problems onto them,” Talia says. “I could tell that was getting too much.” To become less of a burden, she knew she needed to respond to these issues before they spiraled out of control.

Much to my parents’ dismay, Talia talked to her doctor about medication before regularly seeing a psychotherapist. I understand their concerns about jumping to medication too quickly—from their perspective there was a rapid turnaround between seeking treatment and starting the meds. What they weren’t privy to, though, were the years of internal anxiety and the multiple consultations with doctors that led to Talia’s decision. Aside from her medical anxieties, she was confident that this was the right choice. She does not feel she was held back by internalized stigma in the same way that I was.

I admired that Talia was not stopped by shame, or self-sabotage, but I could not navigate the process in the same way. Looking back, I can see that I openly encouraged Talia to try medication, and later Sarena as well, even as I continued to resist it for myself. I understand now that it is inherently different when it is you, because taking medication for your brain comes up against our ideas of personhood. Having an over-achieving, perfectionist personality type—the kind often found in young women—makes me more likely to suffer from anxiety. At the same time, it made me less willing to give in to something that could help me, and more insistent on toughing it out. It’s a trap I fell into easily, and it was a barrier to accepting the help I deserved.

Talia’s Commute, Before and After Medication

Talia is 23, and she is taking the subway downtown to her new job as a graphic designer for Penguin Random House. She is excited, and the commute is easy. To pass the time she listens to Harry Potter audiobooks. She keeps her hands occupied by playing Bejeweled on her phone. As she approaches her stop, she recalls what this experience used to be like—before she had the help of medication. Riding the subway was a major anxiety-inducing event. An announcement of a delay spelled disaster: stuck underground, with no access to a bathroom for an unknown period. What was a minor need to pee became a body in peril. She started sweating. She found it harder to breathe. She was hot, her heart was racing, and she couldn’t calm herself down. The thought spirals would continue until she reached her stop and departed the train.

With medication, riding the subway is a radically different experience. Talia does not worry about delays or needing to get to a bathroom. If those thoughts do cross her mind, she can rationalize them. If panic starts to rise, her brain has a much easier time pushing it back down. Now, if she takes the subway with a friend, she can be present in a conversation rather than being lost in her own tornado of worry. Medication has not cured Talia’s anxiety, but it has made the rational voice in her head much louder than it used to be, allowing her the freedom to get around the city without anguish.