Across campuses and, well, everywhere, Muslims are pinched for space to do their five daily prayers—it’s time to get creative

BY HAJIR BUTT

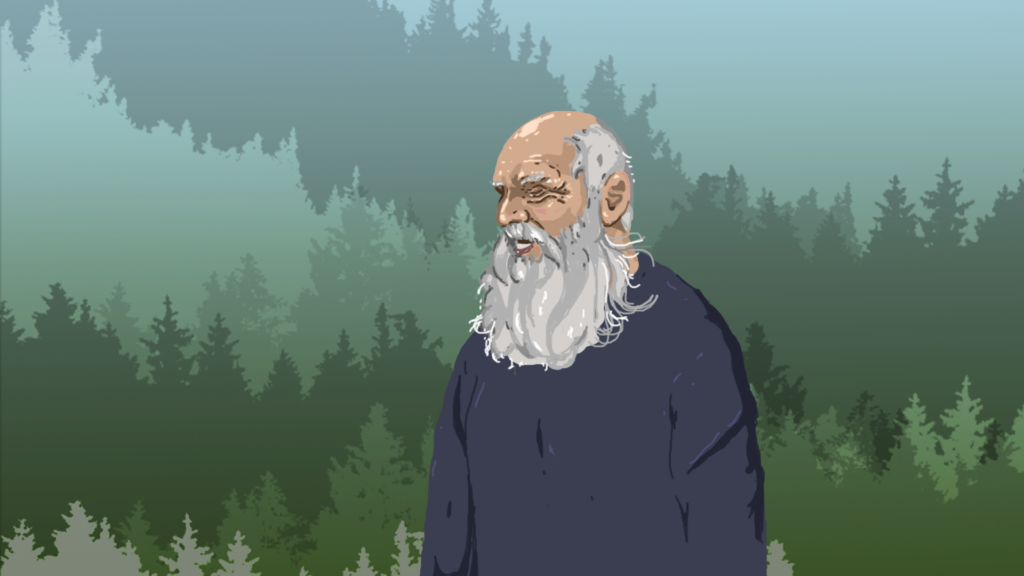

ART BY SAMAN DARA

———————————————————–

There is an inescapable thrill that comes with sprinting to the closest prayer room during the five-minute break in an hours-long journalism lab, hoping to return before the professor switches to the next slide. Sitting in class the other day, the build-up of this thrill was imminent. My phone buzzed during the lecture, announcing it was time to pray. My legs twitched impatiently in preparation for what was to come. As the professor announced the break, I pushed my chair out slightly, ready to start the race to make one of my obligatory prayers. I left my heavy backpack behind and calmly exited the lecture. However, as soon as the door closed, that feigned nonchalance escaped me along with any composure as I sprinted down the steep flight of stairs at the Rogers Communication Centre (RCC).

It’s a requirement for Muslims to take time out of their days to pray, to show gratitude for the blessing of life, and to praise God. Each prayer is at a specific time and must be completed within a certain time frame before the next one rolls around. There are five prayers in a day, one before sunrise, one in the early afternoon, one in the late afternoon, one at sundown, and one at night. Each prayer must be performed in order. Missing a prayer is like missing a bus—inconvenient and troublesome, leaving you with the feeling of defeat.

The nearest and only prayer room on Toronto Metropolitan University’s (TMU) main campus is on the third floor of the Sheldon & Tracy Levy Student Learning Centre, at Yonge and Gould Streets in downtown Toronto. Red street lights held me back as I waited to cross. Students in front of me walked slowly and unaware. The relief from pushing the Student Centre’s door open dissipated as quickly as it came.

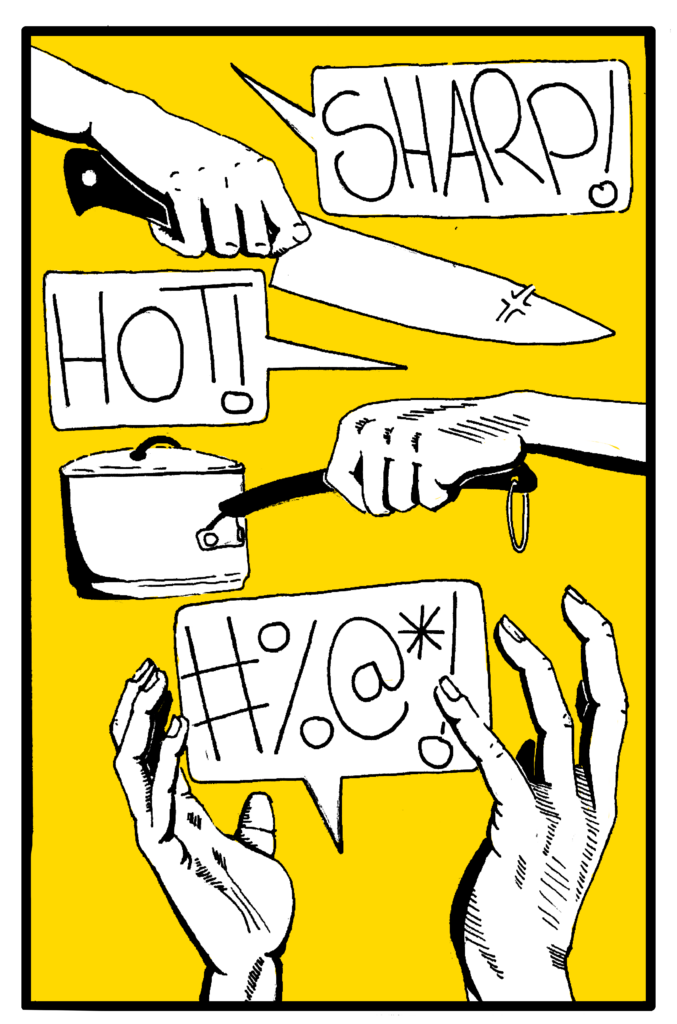

Two flights of stairs made the journey harder. Taking the elevator might’ve been faster, but who knows how long I would have waited for that rickety thing. I shouldered open the bathroom to perform wudu, or ablution. This ritual cleansing before we pray includes washing our hands, mouth, face, arms, ears, hair, and feet. The water travelled down my arms, cold and unforgiving. I took off my shoe and balanced on one foot to prevent myself from touching the grimy bathroom floor. As usual, there were no paper towels, but there was a single air dryer. I preferred not to put my dripping face under the dirty fan. Instead, I used my hijab to dry my damp face, slightly smearing my makeup on the black fabric. I put my shoes back on, only to take them off a minute later before entering the multi-faith room.

Finally, I was standing on the soft, red rug, raising my hands in prayer.

Peace.

The racing heart in my chest slowed. The drumming in my head quieted. Prostrating on the itchy carpet felt like the only position I wanted to be in. I didn’t hear anything, I didn’t see anything, but when I turned my head toward each shoulder to end the prayer, like a nod of farewell to God, my eyes darted to the clock. The nagging digital numbers blared in a red font alerting me that it had been more than five minutes since I left class. Part of the prayer required me to remain seated for a few moments to remember God, but I frantically left the room. Running back was a moment of déjà vu with slow walkers and red lights. I was late. Notes would have to be whispered to me by my peers about what I missed. I was sore. Out of breath. Unfulfilled.

My classmates and professor glanced in my direction as I pushed the lecture room’s door open. They probably thought I went out for lunch and carelessly lost track of time. I tried to keep from blushing as I returned to my seat as quietly as possible.

Every week I perform this draining ritual. It’s as if I’m in one of those movies where the main character is stuck in a time loop, helplessly reliving moments again and again. Muslims experience this moment across TMU’s campus, each participating in a race against time with a backpack of stress on their shoulders and an overwhelming sense of pressure to be a good student, and a good Muslim.

The Journey to a Prayer Room

Hadiyah Khalil knows this ritual well. A third-year student at TMU with a full schedule of classes, she wakes up before the sun rises, at 5:30 in the morning. Her commute is a lengthy one hour each way and some of her classes take place during prayer times. Khalil often waits until class is finished, not wanting to miss anything important, but tries her best to quickly get home afterwards so she has enough time to pray. The experience of praying on campus, she says, takes much longer than praying at home. Going up the stairs, making wudu, unpacking her bags, settling into prayer, then packing them up again takes around twenty minutes longer than it should. Usually, on average, a prayer itself is supposed to take five minutes, with a few minutes afterwards to reflect. She calls the rush to prayer rooms “a whole journey.”

“For a lot of Muslims, their life pretty much revolves around prayer,” Khalil says.

“I’ve seen a lot of them praying on the staircases and in the stairwell,” she says. “It shouldn’t be that way.” Khalil wonders what it would be like to just pray anywhere without feeling judged or nervous. “Praying in a mosque or prayer room is the safest place for Muslims to pray as there is no worry of Islamophobia. You’re with your community,” Khalil says. In these spaces, she doesn’t have to worry about her safety.

The feeling of watchful eyes on the back of our heads as we pray on campus never fails to be unsettling. We find ourselves fidgeting and thinking about what everyone else might be thinking about us. We shuffle our feet side to side, find our eyes shifting left to right. When we bow our heads to the ground, it feels as if we are trying to shrink ourselves in hiding. When we pray, Islam tells us to “empty our heart in prayer,” which is known in Arabic as “khushoo,” so that we can be more present in the moment and benefit more from it. Our goal is to always achieve that. As much as we strive to do so, with the distractions of people walking by, it becomes more challenging. It doesn’t feel safe, comfortable, or peaceful—all things a prayer should be.

The stress of the commute, classes, homework, and everything being a student entails, dissipated as I put my forehead on the carpet that feels just like the one at my local masjid.

There’s Room for Improvement

The Muslim Student Association (MSA) at TMU advocates for more spaces and resources on campus to make Muslim students feel the sense of safety we seek. MSA’s president, Abdullah Patel, is a fifth-year marketing student and has been a part of MSA since year one. It was a full-circle moment for him to become president. Since he joined, MSA has come a long way. “We’ve grown and become a big community,” Patel says.

In 2023, the MSA added an extra prayer room at the Ted Rogers School of Management Building (TRSM). Patel found that people didn’t realize how much that room was needed and how much having an extra space could benefit the community. Patel says the association presented faculty with statistics to show the need for more space. This made the idea of another prayer room a reality.

Before, the lack of rooms proved inconvenient. “I remember being frustrated and telling the people in charge of MSA at the time, like, ‘Hey, I don’t have a place to pray.’” He recalls how he used to pray in stairwells, too. Using prayer mats packed in backpacks and dusting the dirty stairwell floors, students would pray, hoping no one decided to take the stairs instead of the elevator. Or worse, Patel says, “getting locked in the stairwells.”

It took MSA several years to get a second prayer room at TMU. The process included petitions and a push from the Muslim student body, with students feeling that an extra space on campus would save them more time and energy. Even so, the room can only accommodate ten people. Considering the number of students and staff who frequent it, the space isn’t ideal. It’s also located outside of the main campus, about a ten-minute walk from most TMU facilities. As for the multi-faith room on the third floor of the Student Centre, the room gets so crowded that they have to perform three to four separate sessions for each prayer because of the sheer number of students. Not only is the room used for prayer but you can also find students studying with their backs to the wall or even taking a nap on the pillows in the corner of the room. And while TMU lends Muslim students a room in the International Living Centre (ILC) every Friday for Jummuah—an obligatory congregational prayer and sermon—the space only holds 100 people, while 160 students on average attend the sermon.

Other fields that could be improved are the issues with the bathrooms in the Student Centre. “We don’t have paper towel dispensers in the wudu area,” Patel says. “It’s not on top of their priority list.” I can’t help but laugh as I recall my soggy sleeves and cold face just a few hours ago as I made wudu. Despite the need for more consideration, Patel appreciates the spaces Muslim students have in the university. “We’ve been really lucky to have a supportive school.”

Our conversation concluded as MSA staff started to prepare for their first Jummah. There are four Jummahs in one day to accommodate all the students. I decided to stay and attend. There was a sense of camaraderie as MSA spread the rugs on the floor and put the barrier between the men’s and women’s sections. Muslim students embraced each other in hugs and began to sit down to listen to the speaker’s talk.

Once it concluded, we all stood, standing shoulder to shoulder in prayer and hanging on to every word recited from the Quran. The verse: “Only You we worship and serve, and only You we ask for help. Guide us to the straight path,” never fails to put my mind at ease, to remind me why it is that we try our best to catch a prayer or strive for excellence.

The stress of the commute, classes, homework, and everything being a student entails, dissipated as I put my forehead on the carpet that feels just like the one at my local masjid. I didn’t have any classes to rush to afterwards. My mind didn’t have to calculate the best way to get to class or what to tell my professor. I wished I had this every day.

What More Can Be Done?

As Patel says, there is much to be grateful for at TMU. The lending of the space at the ILC, and the extra prayer room at TRSM, but, I wonder what else can be done to make every day feel more like Friday prayer.

When I contacted TMU, asking to speak with someone who could discuss the facilitations of the rooms, and who exactly has a say in the number of multi-faith rooms, I was given the following statement: “A diverse and inclusive environment promotes a sense of belonging and helps us better understand and meet the needs of our multifaceted community.” They further explained that they do not handle the rooms and directed me to the Student Union. I’ve yet to hear back from them.

While the sense of community and diversity is felt on campus, more layers of understanding can be implemented and addressed to further benefit every faith-based community at TMU. Chiefly, faculties could expand their knowledge of different cultures on campus. Musab Mobashir, a TMU engineering graduate who also completed studies at the Al Khalil Academy for Islamic Knowledge a few years later, thinks universities could be more considerate to Muslim students. “The first thing is to educate teachers and faculty on what is expected and what the needs of a Muslim student are,” he says. “It could be fasting, it could be prayer—basic stuff.”

The lack of understanding can often be felt when we are forced to pray in random rooms and explain ourselves again and again to professors. I certainly felt it on the first day of university.

We want to pray with ease for ourselves and our God.

From Bathrooms to Stairwells

As a first-year, the terrain of the campus was mysterious. I needed to pray and I wasn’t brave enough to do so in public. I had to muster the courage to ask a faculty member sitting in her office. “Is there any quiet area for me to pray here?” I asked, adding “I’m sorry to bother you” and “I’m sorry for any inconvenience,” among other apologies. Her lips went into a thin line as she thought of somewhere. My gut felt twisted at having to ask, afraid that I might get scolded or face repercussions. However, hope swelled as she got up from her chair and took me to a room, opening the door. I anticipated it to be an empty office or a classroom. Maybe even a broom closet. “Here, there is a lock on this washroom.” A broom closet would have been better.

The professor closed the door behind her and I stood there in a trance of shock and disbelief. I was facing toilets, standing on a sticky floor, and smelling scents that were far from pleasant. I did not know how to call her back and tell her that my prayer was not to be disrespected by putting my forehead on the ground where people go to relieve themselves. They should at least know that. The room felt like it was closing in on me, and I pushed open the door, determined to find somewhere else. I walked all over campus until I happened upon the multi-faith room.

Zayneb Al-Hantoshi didn’t know about the prayer room, either. Not until second year. And when she found out, she was far from impressed. The lack of cleanliness, the water everywhere, and, of course, the lack of paper towels, were a deterrent. Nonetheless, Al-Hantoshi would rather face those struggles than delay her prayers. “It’s something I can’t miss,” she says. “It’s not something I’m just gonna go home and do.”

Wudu is to be made every time you pray. However, if you make it once without using the washroom or sleeping afterwards, you don’t have to make it again. So, Al-Hantoshi tried that. Not doing things, though, is harder than it seems. Trying to stay awake in classes, on the bus, and not using the washroom in an attempt to avoid the inconvenience of making wudu in a restroom that has no comfortable means to dry off, adds more stress. “It just makes me uncomfortable,” Al-Hantoshi says, bunching her shoulders at the thought.

We have two prayer rooms at TMU and a bathroom with limited resources. Surely, there must be universities that have more. I couldn’t hold back a gasp, slightly jealous, as I found out that the University of Toronto (U of T) has twelve prayer rooms and a whole page on their university website listing all the places one can pray. Maybe ‘slightly’ isn’t the right word. I was immensely jealous as my fingers kept scrolling and it felt like it would never end. These areas consist of multi-faith centres, meditation spaces, clubhouses, or just random rooms where access codes are given out for students to enter. The Robarts Library has a bathroom with a foot-washing station for wudu.

Twelve rooms. That’s ten more than TMU has. I grumbled to myself as I searched, “TMU prayer spaces,” and found no information on the main website, having to deep-dive for it on MSA’s page.

Drew Sieber is a third-year student at U of T. Their name has been changed due to privacy concerns. Before coming to Canada, Sieber lived in different countries, like the United Arab Emirates. “In my high school in the UAE, the prayer rooms were not as nice as they are here at U of T,” they admitted to me on FaceTime while walking around the campus. And relative to what students in European universities experience, Sieber feels accepted at U of T. The multiple prayer rooms have been a great relief. “Most of my classes are all within the same area, which is around St. George.” They show me the campus and the buildings behind them through the phone. “All my classes are next to prayer rooms,” Sieber says. “They’re all so close together.”

Before the addition of these rooms, Basmah Ramadan, former MSA president at U of T, used to struggle with finding a convenient and safe place to pray. Like many others, she would pray in U of T’s stairwells with her blue Islamic Relief prayer mat—a staple many Muslims carry. She would go to a quieter stairwell in the basement of Sydney Smith, where most students rarely go. Yet, she found her heart racing and her mind drifting to whether or not someone would open the stairwell door and come upon a hijabi girl bowing onto the dusty ground. If it wasn’t other students she was worrying about, it was the basement cockroaches and spiders. “In those staircases, you’re either praying really quickly just so people don’t see you, or you’re praying really quickly because you notice an insect that is, like, half dead, half alive, and you want to run for your life,” Ramadan says, laughing. Will someone walk in? What should we do if they do? Do we break our prayer? Continue? These thoughts race in the minds of Muslim students when, instead, we should be thinking of the verses of the Quran we recite in prayer. Now, with twelve prayer spaces on campus, Ramadan finds herself frequenting those more than the spidery stairwells.

“How did you get these rooms?” I ask, silently begging her to tell me their ways.

What took TMU several years, took U of T mere months, according to Ramadan. Getting spaces for prayer was an initiative done by a handful of Muslim students who showed the need for more accessible spaces. The students came forward and explained the necessity of these rooms, reminding the university of their presence.

U of T has done a lot for its Muslim student population. From providing resources like prayer mats to prayer hijabs, most spaces have what’s needed for students. Ramadan believes it’s about ensuring that universities know that the Muslim community isn’t small and takes on more than they are aware of. “We have to host our iftars, we have to host our jummah prayers, our [daily] prayers. So, recognize we have a lot on our plate,” says Ramadan. From juggling our grades, classes, and assignments, to balancing our prayers, faith, and Muslim identity on campus, the pressure is immense. But students do it, “For the sake of Allah,” Ramadan says.

The lack of prayer rooms is not just found in the confines of a university campus. This experience extends to general public spaces, where finding somewhere quiet to pray at work or on a day out is hard, too. A family friend, Mariam Siddiqui, says she could “write a book about all the weird places we’ve prayed.” From movie corridors to restaurants, amusement parks to malls, there are many instances where there are no prayer rooms available. Quite often, it makes way for unconventional spaces to pray.

At parks, Siddiqui and her family look to find any secluded grassy area, using their coats as makeshift prayer mats. “Can’t they get a room?” is a common phrase Siddiqui hears in response. But she’s also been met with kindness and genuine interest in what she is doing.

“Having your own rooms in these spaces would be amazing,” says Siddiqui, but at the same time she finds it all to be an adventure. “It’s a literal open declaration, ‘Yeah we’re Muslim, this is who we are and this is our Earth, too.’ There’s beauty in that.” Sometimes putting your forehead to the ground is an experience that isn’t a bad one, and being able to pray openly affirms her faith. “I’m not going to hide away and pray. I’m going to pray openly.”

We want to pray with ease for ourselves and our God. We want to fulfill our obligations as Muslims, first and foremost. So, if that means getting up and leaving class while the professor is speaking, we will do so. If it means we walk ten minutes and pray in dodgy stairwells or a corner of a room, we will do so. If we have to pray on gravel and grass, we will do it proudly. And while we say we are used to it, we shouldn’t have to be. We shouldn’t have to taint our prayer by rushing when we are supposed to be at peace. We shouldn’t have to turn something that brings us ease into something that brings us hardship. We shouldn’t be expected to pray in bathrooms.

Perhaps more rooms will be made. Or maybe they won’t, and the struggle we face is a struggle that endures. A struggle that we can overcome, transform into our strength and show that, despite all the difficulty, nothing will stop us from fulfilling our duties as Muslims—not even soggy sleeves.